Today is an important date especially in German history, and some of it quite dark. Last year I marked this date with a post that briefly noted the various significant historical aspects of that date but then concentrated on only one of them: the Fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989. It was illustrated with various images of the vestiges of that former border fortification.

Today, however, I want to concentrate on another dark aspect of this date, namely in the year 1938:

9 November 1938 was a day of infamy, when throughout the Third Reich (by then including Austria) Nazi mobs attacked and humiliated Jews openly, destroyed Jewish businesses and desecrated and burned down numerous synagogues. This is now officially referred to as the November Pogrom(s), but is still commonly also known as “Kristallnacht”, typically rendered in English as “Night of Broken Glass”. The older term, and especially its longer form “Reichskristallnacht”, are now avoided as they can be seen as euphemisms. And since the damage indeed went far beyond a bit of broken glass, ‘pogrom’ is the more appropriate term.

It was not the first time Jews were targeted in such ways, but probably the worst up to then. Moreover, it was in a way a precursor of the systematic extermination of the European Jews in the deadliest phase of the Holocaust that was to come during WWII, especially in 1942/43 (see Operation Reinhard).

So for today I decided to give this blog a Jewish theme, in commemoration of the victims (people as well as buildings) of 9 November 1938 in Germany and Austria. … as well as of Jewish victims elsewhere after that date.

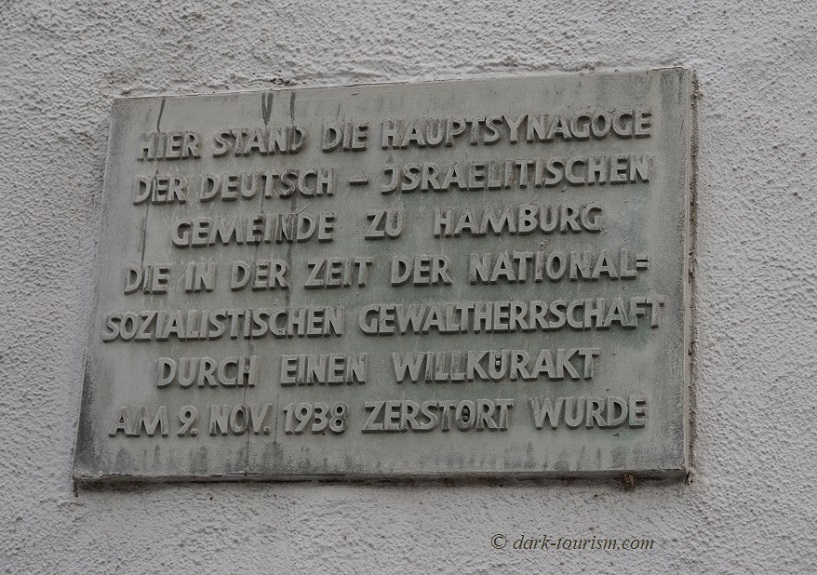

The November Pogrom is actually something I learned about at an early age, long before the topic came up (briefly) in history classes at school. That’s because the neighbourhood I grew up in, the Grindelviertel district in Hamburg, had used to be a Jewish quarter before the Holocaust. Today there’s only a small Jewish community in the city. One vestige of Jewish life that was and still is well visible is the Talmud Torah School (Talmud-Tora-Schule) on Grindelhof. In 2007 the building was given back to the Jewish community, which then moved its headquarters here and also reopened it as a day school. Nearby a plaque on a bare wall marks the location of the former large synagogue on Bornplatz (I lived a stone’s throw away on Bornstraße):

The Bornplatz synagogue, the first free-standing such structure in northern Germany and the largest too, was totally destroyed on 9 November 1938 and the charred but still standing remains were later demolished (Jews were even forced to do this – at their own expense!) Thus the synagogue was wiped off the map entirely. Bornplatz has now been renamed Joseph Carlebach Platz, after the last chief rabbi of the synagogue.

In recent years there has been a campaign for the reconstruction of the synagogue at its original location. This caused controversy, especially amongst a few Jewish representatives, some of whom regarded the idea of such a rebuilding as “changing history” and glossing over Nazi crimes. Others welcomed the idea and it seems that now the decision has been taken to give the reconstruction the go-ahead. That will be interesting to follow.

Perhaps the most celebrated synagogue in Germany is the Neue Synagoge on Oranienburger Straße in Berlin. It too came under attack on 9 November 1938. Nazis broke in and prepared to burn the building down, but a courageous police officer on duty that night drew his pistol and ordered the mob to be dispersed. That way the fire brigade was able to put the fire out before it could do too much damage. However, damage did come later, namely through aerial bombing by the Allies. The rear with the main congregation hall was badly hit and later demolished after the war. Only part of the front façade and some rooms immediately behind it survived, but the iconic central dome was torn down. It wasn’t until the late 1980s/early 1990s that the front of the synagogue was fully restored, including the Moorish dome. The main part of the rear, however, remains an empty space. Below is a golden-hour photo of part of the front façade of the New Synagogue in Berlin:

Note the two vapour trails from planes in the sky behind the synagogue forming what looks like a Christian cross! This is of course purely coincidental, but I found it an intriguing juxtaposition.

But looking beyond Germany, here are some more photos of related places. First of all, a similarly grand synagogue building in Budapest, Hungary, the Great Synagogue on Dohány Street, currently the largest working synagogue in Europe, seating as many as 3000 people:

Also in Budapest is the Hungarian Holocaust Memorial Center, which incorporates the beautifully restored Páva Synagogue. Originally constructed in the 1920s, the restored building was reopened as a memorial in 2004:

And in Romania’s capital city Bucharest I found this former synagogue:

The interior of this synagogue, called United Holy Temple Synagogue, is home to a Jewish Museum, which includes a section about the Holocaust too. The photo featured at the top of this blog post was also taken here. Here’s a view of the interior of the synagogue-cum-museum from the upper gallery:

Another capital city in Eastern Europe with a strong Jewish heritage is Prague in the Czech Republic. Its old Jewish quarter is indeed one of the key tourist attractions of the city. The densely stacked matzevot (Jewish gravestones) in Prague’s Old Jewish Cemetery are world-famous. Adjacent to the cemetery is one of the Jewish quarter’s several synagogues, this is the Klausen Synagogue Ceremonial Hall, now a museum:

A Jewish community that suffered especially at the hands of the Nazis during WWII was that of Lithuania. The capital Vilnius was once known as the “Jerusalem of the North”. But in the Holocaust some 95% of all Lithuanian Jews, almost 200,000 people, were murdered (see also Ponary and the 9th Fort). The country’s second city, Kaunas, was also home to a large Jewish community and once had 25 synagogues. Today only this choral synagogue in Kaunas survives:

Latvia to the north of Lithuania suffered a similar fate, though the numbers were somewhat lower. But still around two thirds of the once ca. 95,000 Latvian Jews also perished in the Holocaust (see Riga Ghetto Museum, Rumbula and Bikernieku). The largest synagogue in the capital Riga, its Great Choral Synagogue was burned down by the Nazis on 4 July 1941. The ruin was then demolished by the Soviets and it wasn’t until 1993 that a reconstruction was unveiled as a memorial at the site. Apparently it incorporates some authentic fragments from the original synagogue:

And now a big jump – across the Big Pond to South America, namely to Suriname (the former Dutch Guiana), more precisely to Jodensavanne (‘Jewish Savannah’). Here, deep in the jungle by the Suriname River, a Sephardi Jewish community was given refuge and developed into a prospering plantation between the 17th and early 19th centuries. Today all that remains are a few graves and the brick ruins of the Beracha ve Shalom Synagogue, seen in this photo taken in 2019:

Back in Europe and in yet another Eastern European country, here’s a ruined and abandoned synagogue (or maybe just a large mausoleum?) at the Jewish cemetery of Chișinău, the capital of Moldova:

Finally, not a synagogue, but something directly related to our starting point, 9 November 1938, the “Night of Broken Glass”. This sculpture is part of the Memorial against War and Fascism by Alfred Hrdlicka (remember him from last week’s cemetery post?) on Albertinaplatz here in Vienna:

This is called “The Street-Washing Jew” and is a reference to the humiliation many Jews suffered when enthusiastic Nazis on 9 November 1938 made Jews scrub the pavement and streets. This came only a short while after the Anschluss of Austria when many Austrians enthusiastically welcomed the arrival of German Nazism (and their fellow Austrian-by-birth Adolf Hitler).

This memorial complex has always been controversial. Conservative Austrians did not welcome such a reminder of Austria’s complicity in Nazism (preferring the notion of Austria having been the “first victim” of Nazi expansionism rather than the active collaborator it was in reality). On the other hand, the depiction of the humiliated Jew as a standard cliché of a bearded old man in traditional and wearing a kippa was criticized by Jewish representatives as reinforcing perceptions of Jews too close to the Nazis’ own clichéd depiction of Jews in their propaganda. Also the fact that today’s visitors physically have to look down on this figure, as it is only a foot and a half (50 cm) high, caused criticism. Others criticized the very fact that only one of the victims was depicted but not any of the perpetrators and the cheering hordes of bystanders.

Despite Hrdlicka’s undoubtedly good intentions, the monument failed to confront contemporary Austrians with their country’s part in Nazi history. Some were evidently unaware enough to misuse the sculpture to sit on eating ice cream or whatever – unintentionally (one would hope) adding extra humiliation to the depicted Jew. As a reaction to such people’s unthinking behaviour, the authorities had the monument removed and altered and then returned to its original location, but now ironically with added oversized barbed wire on the man’s back. While those metal spikes helped prevent people sitting on the sculpture, it also added unwelcome extra associations e.g. with concentration camps – and some claimed also to Christianity, seeing a similarity of the artistic barbed wire to Jesus’s crown of thorns.

In the photo above, taken a few years back several days after 9 November you can also see some wilted flowers, a wreath and two red candle holders (see again last weeks’ All Saints’ Day blog post). One could argue that at least the latter are also too much of a Christian tradition to impose on the depiction of a devout Jew. But maybe that is too much over-interpretation. Anyway, all this goes to show what a tricky tightrope walk it can be to design a memorial monument to such ‘difficult heritage’ (so the scholarly term goes), and how perceptions can also change over time. Even the most well-meaning approaches can get into trouble over alternative interpretations and shifting taboos.

2 responses

Fascinating post.

thanks!