Today is one of the most significant international remembrance days, on the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz on this day in 1945. Last year I gave you a blog post about Auschwitz that was largely compiled from older posts on this date taken from my archive of posts on the Dark Tourism page I used to curate on Facebook until that, and my personal account, were brutally purged by the company.

Today I’ll cast the net wider. It’s impossible to cover every Holocaust-related dark-tourism site in a single post (on my main website there are listed 77 such places that are covered on the site – and that’s in addition to the concentration camps and death camps!). But what I can do is give one photo each from all the main concentration camps and death camps, i.e. the main places where the Holocaust played out (in addition to numerous massacre sites, which, again, are too many to list exhaustively – examples include Babi Yar, Rumbula and Ponary).

The first photo, obviously enough has to be one from Auschwitz. And other than the infamous “Arbeit macht frei” sign over the gate of Auschwitz I, the gatehouse of the larger Auschwitz II Birkenau camp is so iconic that it featured on the cover of the first-ever book about dark tourism, also on page 170 of my own book Atlas of Dark Destinations, and is also incorporated in my website’s logo, reproduced at the top of the blog page too :

(This photo is also the same as the featured photo at the top of this particular post.)

Auschwitz is the one name in this context that just about everybody is familiar with. But it has also caused confusion. That is because Auschwitz served a dual role, namely both that of a concentration camp and that of a death camp. There’s a crucial distinction here: concentration camps were for ‘concentrating’ a large number of prisoners in one place, thus taking them out of society – the concept was first developed not by Germany but by Spain and Britain (the first larger such camps were set up by British colonialists in South Africa during the Second Boer War at the beginning of the 20th century). The Nazis “perfected” the concept from 1933 onwards and first used them to imprison political opponents, but soon also Jews, and increasingly exploited them for forced labour. The conditions were inhumane and many perished (hence the expression of “Vernichtung durch Arbeit”, ‘extermination through labour’), but these concentration camps were still very different in principle from the later death camps, which were set up specifically for mass murder on an industrial scale and not for exploitation of labour. Auschwitz, though, did both. Thousands and thousands had to work, but hundreds of thousands more were brought here to be sent straight to the gas chambers. But this dual role was very much the exception. One other camp is sometimes regarded as having had a similar dual role (though on much less a massive scale as a death camp than Auschwitz), namely Majdanek near Lublin. Another similarity with Auschwitz is that at Majdanek, too, the disinfectant chemical Zyklon-B was used for gassing. At the memorial site today, there’s a room next to the former gas chambers where over two hundred Zyklon-B gas canisters are stacked high – a truly spooky sight to behold:

The true death camps were different in that they were much smaller, without those endless rows of barracks, and their only role was that of mass gassing of Jews brought in trainload by trainload from all over the Nazi-German-controlled lands and from ghettoes and other camps. This was the so-called Aktion Reinhard, named after Reinhard Heydrich who in January 1942 had chaired the Wannsee conference – see also last year’s post about this.

The three Operation Reinhard camps were purpose-built in secluded locations in occupied remote eastern Poland, but always near existing railway lines. These death camps were: Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka. All three utilized gas chambers using exhaust fumes from tank engines. After the war, these sites were long neglected and only after the end of communism in Poland have they gradually been commodified for visitors. At Bełżec a large modern memorial has been built which includes a symbolic recreation of the “Schlauch”, or ‘hose’, the fenced pathway victims were herded along towards the gas chambers:

Almost nothing original survived of these three death camps because they were systematically dismantled and ploughed over by the Nazis once they had fulfilled their purpose. But there are a few relics still in place today, in particular this part of the ramp and railway spur at Sobibór:

Sobibór, long the most neglected of the death camp sites, has more recently also seen lots of archaeological work and the creation of a state-of-the-art museum and now has to rank as the best commodified memorial of this kind. The site of the deadliest of the three Operation Reinhard camps, Treblinka (where around 900,000 Jews were killed within just 15 months or so), lacks a modern museum but features a large and elaborate sculpture arrangement with a central monument within a field of rocks representing all the places from where the victims had come:

A kind of precursor to the Aktion Reinhard camps was Chełmno, though this wasn’t a camp as such, but primarily an appropriated manor house at which the Nazis “pioneered” killing by means of exhaust gas. Here special airtight “gas vans” were first used in “experimental” gassings, utilizing the van’s own exhaust fumes. But this was later put to systematic use too, in particular during the extermination of most of the 160,000 inhabitants of the ghetto of the nearby city of Łodz. Again, next to nothing authentic remains of this place other than these remnants of the foundations of the former manor house:

Another place where such gas vans were used in systematic killings was Maly Trostenets near Minsk in Belarus. This camp is therefore sometimes also classed as a ‘death camp’. Again, virtually nothing of the original structures remains and the site had long been neglected until in more recent years it was turned into an open-air memorial complex. At its centre stands a new large monument featuring artistic depictions of victims, as in this photo:

Other sites of former concentration camps have also disappeared and are marked by no more than monuments, such as this humble one at the site of the former camp of Kaiserwald in Riga, Latvia:

Kaiserwald was not an extermination camp but a comparatively small camp for housing forced labourers, yet virtually none of them survived the war.

Also near Riga is the site of yet another camp of which nothing original remains: Salaspils. There is also very little information about the place. It was probably more a penal and forced labour camp and operated between 1941 and late 1944, when it was liberated by the Soviet Red Army. In 1967, a very Soviet monument complex was constructed at the site, featuring ensembles of large concrete statues, as seen in this next photo:

More has been preserved at the main camps further west. Stutthof was the concentration camp for Gdańsk, and here parts of the original structures survived, such as the crematorium. When I visited this memorial site in the summer of 2008 it was a dull day, and thus many of the locals who were holidaying on the nearby beaches instead headed inland to see what else there was to do on a “museum day” like this. And so there was an unusually large number of people visiting this memorial (many clearly what I call “accidental” or “casual dark tourists”), including whole families, many with small children – even though it said on a sign by the gate “not suitable for under 14-year-olds”. This created a bizarre family-outing atmosphere, in a most unlikely location, in which I was able to take a photo of this bizarre juxtaposition:

Also in Poland is the former concentration camp of Groß-Rosen not far from the city of Wrocław, the former Breslau. When I say “in Poland” then that should really be “now in Poland”, because at the time of the camp’s operation it was still on German territory, namely in Lower Silesia, but that was one of the German territories that was given to Poland after WWII. The memorial museum at Groß-Rosen is not as elaborate as some within Germany today and probably struggles with funding, but still has some original structures and artefacts on display. This includes one of the most prototypical displays at such sites: those striped inmate clothes and wooden shoes:

The very first KZ (short for “Konzentrationslager”, the German for ‘concentration camp’) was Dachau, which is probably also the second best known name of such a camp after Auschwitz. Initially Dachau and other early camps were primarily for the incarceration of communists and other political opponents. Later other “undesirables” were brought here too, including Jews, so it’s also a Holocaust site, even though initially it wasn’t intended as such. Like most of the larger camps, Dachau also had its own crematorium, which is now one of the most poignant original structures to be found at today’s substantial memorial centre:

Dachau is near Munich, which was the “Hauptstadt der Bewegung” (‘capital of the Nazi movement’); but the second KZ to be established was near the real capital Berlin, namely Sachsenhausen at Oranienburg. Amongst the original structures still to be found there is this creepy dissection room:

Many people seem to be under the impression that most killings at the concentration camps were done by gassing. But outside the death camps in the East that was by no means the case. Most deaths were caused by exhaustion, malnutrition and disease. But there were also executions. Common methods were hanging or shooting, but also injection of phenol directly into the heart. At the old documentation centre at the large concentration camp memorial of Buchenwald a syringe employed for that purpose used to be on display:

A few years ago, the documentation centre at Buchenwald underwent a substantial overhaul and reorganization. In the wake of this, a large part of the countless original artefacts formerly on display were removed from the exhibition, including this syringe (all these things are now in storage). Instead, the exhibition follows the current trend towards more and more interactive media stations with touchscreens and such like. Personally, I find that development not so welcome. Staring at screens and scrolling through pages is something I can easily do at home. When I visit an authentic dark site I want place authenticity not just in buildings but also in artefacts. They touch me more than yet another graph of statistics or lists of names. But it’s reckoned that interactive screens are the way to go in order to keep younger visitors engaged. Oh well.

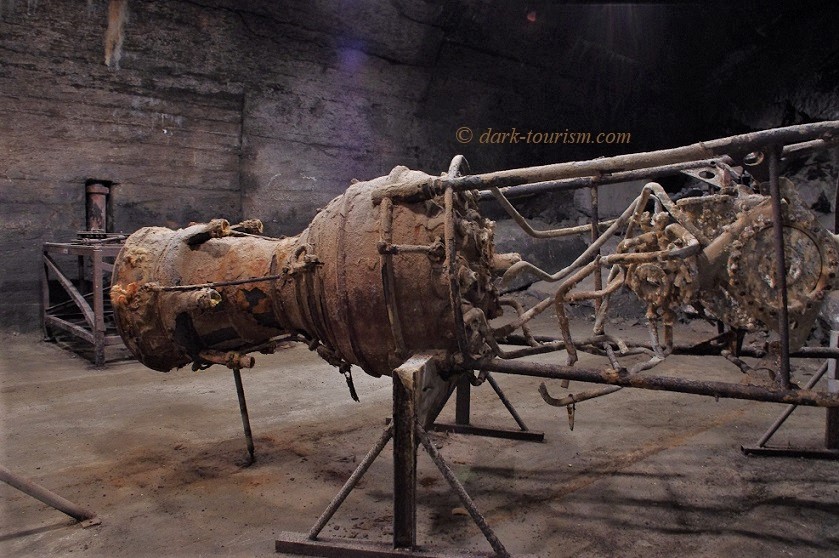

Originally a satellite camp of Buchenwald’s, established in 1943, but later (in October 1944) turned into a main camp with its own administration was Mittelbau-Dora. This was set up for underground forced labour, and many inmates also had their squalid “living quarters” underground, namely in tunnels driven deep into a mountain, safe from Allied aerial bombing. Here an underground assembly factory churned out mass-produced V1s and V2s, the infamous flying bombs and missiles used as pure terror weapons especially against Britain. At Mittelbau-Dora today, a section of the tunnel system has been made accessible for visitors on guided tours. And amongst the debris to be found here is this rusty old V2-missile engine propped up as an exhibit:

One of the least well-known concentration camps was Flossenbürg in Franconia, north-eastern Bavaria. Amongst the preserved original structures here is this tiled former communal shower room:

And no, this shower room was never used for gassing but was a genuine shower room. It is true that some gas chambers in the death camps were disguised as shower rooms (though the gas never came through the shower heads – as another common misconception has it), but at the “regular” concentration camps within Germany like Flossenbürg, this was not the case.

The northernmost main concentration camp in the west was Neuengamme near Hamburg. Today’s vast memorial site is quite different in its appearance from other such camp memorials, but it does feature one thing that is comparatively common to many of them, namely the display of an original deportation rail car from the Holocaust:

One of the large main concentration camps was predominantly for women, namely Ravensbrück. Large parts of the camp’s grounds were used by the Soviet military after the war, so that a proper commemoration only began after their departure in the 1990s. A few years ago an extensive historical exhibition was finally opened in what used to be the main administrative building of Ravensbrück, seen in this next photo:

What Buchenwald and Dachau were for the Americans (and Majdanek for the Soviets), Bergen-Belsen was for the British – the first direct encounter with the horrors of the concentration camps full of barely living skeletons and heaps of equally emaciated corpses. Because the camp was so disease-infested, it was raised to the ground. So today hardly anything at all survives at the site, which is basically just a clearing in the forest with a few monuments dotted around:

Bergen-Belsen started out as a POW camp (like Sandbostel) and was turned into a fully fledged concentration camp only in 1944, when the camps in the east were “evacuated” as the Red Army pushed westwards. Belsen thus became an “overflow” camp, and naturally the inmates arriving here after long death marches and transports towards the end of the war were the most emaciated. Among the victims were Anne Frank and her elder sister Margot, who both died here of typhus just weeks before the camp was liberated. In the 2000s, a modern documentation centre was added next to the site of the camp and this provides rich information about this historical place and its dark context.

As soon as Nazi Germany had annexed Hitler’s home country of Austria (in the so-called “Anschluss”) in 1938, a large concentration camp was set up here too, which in fact became one of the most notorious ones: Mauthausen. Its most infamous part was the so-called “Todesstiege” (‘death stairs’), which today looks like this:

Camp prisoners had to do forced labour mostly in an adjacent quarry and then carry their heavy loads up these steep stairs where they often collapsed exhausted. The SS, moreover, had “fun” pushing inmates over the edge at the top of the stairs and the quarry so that they’d fall to their death. Cynically they called their victims “Fallschirmspringer”, ‘parachutists’.

Mauthausen was only one of several camps next to a quarry from which inmates cut all the big blocks of rock that the Nazis needed for their grandiose intimidation architecture. Groß-Rosen and Flossenbürg (see above) served the same main purpose. Yet another camp also falls into this category, Natzweiler-Struthof in Alsace, a territory annexed from France in 1940, but returned to France after WWII. Today’s memorial is thus the only one of its kind on French soil. It incorporates many original structures. Here’s a photo of the roll-call square, the gallows and some quarry trolleys:

Another territory annexed by the Nazis early on was Czech Bohemia and Moravia. And here they turned the fortress and garrison of Theresienstadt (Terezin in Czech) into a concentration camp and ghetto too. For a while it was a “Vorzeigelager”, a ‘model camp’, in which conditions were made to look less harsh so that invited Red Cross inspectors could tell the world that it wasn’t all so bad. Yet, Theresienstadt was a tough place too; when no inspectors were looking probably just as bad as other camps. And you also find that infamous slogan “Arbeit macht frei” (‘work makes you free’) here:

Another concentration camp on occupied territory was Vught in the Netherlands, aka KZ Herzogenbusch (as it is near the town of ‘s-Hertogenbosch). Today, part of the former camp’s grounds serve as a National Memorial. There are few original structures accessible to the public, but fences and some watchtowers have been faithfully reconstructed:

After Mussolini was deposed and Italy surrendered to the Allies in 1943, this led to the subsequent takeover of the northern part of the country by Nazi Germany, and so concentration camps were established here too. One example is the Risiera di San Sabba, a former rice mill that was converted for this purpose by the Nazis in the city of Trieste:

There were other such sites too, but it’s not always clear whether the term ‘concentration camps’ should really be applied for such repurposed sites as well, or whether the term should be reserved only for the large main camps. Moreover, all those main camps had “Außenlager”, ‘subcamps’ or ‘satellite camps’, often hundreds of them. In a few cases these grew to sizes similar to the proper main camps. A prime example is Gusen, a satellite camp of Mauthausen, which eventually ended up bigger than the main camp.

I’ve been to all the sites covered above, plus many more satellite camp sites and other related places. I could say that I’ve managed to visit all the main concentration camps – except that there is one more contender, namely Płaszów on the edge of Kraków in Poland, which I failed to go to on my visit in 2008 (time was short). I know there isn’t much left at the site, but next time I make it to that part of the world, I’ll have to explore the location of the Płaszów camp as much as is possible.

But so much for an overview of the main sites of the Nazi camps marking today’s Holocaust Remembrance Day. I’d like to say that the preservation of what’s left of these very dark sites is an essential element of this remembrance effort and dark tourism is very much part of this. In fact, Holocaust remembrance tourism is one of the most prototypical types of dark tourism. So I thought this deserved this elaborate blog post, which has indeed become one of the longest ever posted here!

2 responses

Great post as always Peter. I would love to see a post on some of the massacre sites. I’ve been to a few myself but not too many.

that might be something for Holocaust Remembrance Day next year … unless I do it before. There’s generally not much to see at these sites, although Babi Yar is set to get a museum added soon … and Ponary’s already had one for a long time. But the others are rather abstract. Still, very sombre places.