Sunday’s announcement that Putin has put Russia’s nuclear forces on “high alert” really knocked me off balance. You see, I’m a child of the Cold War … I came of age in the early 1980s, at the very height of the Cold War, one of its most dangerous phases, in fact. I remember the so-called “Star Wars program” and the demonstrations against the American Pershing II mid-range missile deployments in response to the Soviets’ SS-20s. This cut the forewarning time of nuclear war from half an hour to something like 10 minutes max. And so I became increasingly aware that any minute could be my last.

I’m somewhat reminded of that feeling now. Although there are significant differences: for one thing, back then it was a very slow and gradual realization of what the threat was, one that had already so normalized in the Cold-War era even before I was born. Now it’s more shocking, because it came so suddenly. Another difference is that any potential use of nuclear weapons in the current crisis would probably not be an all-out firing off of the entire arsenal, but more likely a step-by-step escalation. So more painfully drawn out.

I sincerely hope it will not come to that, but at the minute I’m really no longer ruling anything out. But let’s hope that negotiations manage to de-escalate the situation. Although, reading this article today (external link; opens in a new tab), which says we’re already in the middle of a Third World War, put a serious damper on such hopes …

.

But this is a dark-tourism blog, and even though tourism is a tiny, insignificant issue in comparison to this new war in Europe, I still feel I should get back on topic … but with a thematic link to the nuclear threat issue:

So here’s something about nuclear tourism from Ukraine – and it’s not Chernobyl:

Just over three years ago, in November 2018, was the last time I visited Ukraine. This was indeed primarily for another two-day trip to Chernobyl (this time accompanied by a German journalist who was doing a feature about dark tourism and me for the SPIEGEL). But before we made our way to Slavutych, from where we’d take the train to Chernobyl the next morning, we went on an excursion to the former strategic missile base of Pervomaisk, now a museum of sorts (btw. this is not the Pervomaisk near Luhansk but the one south of Kyiv roughly halfway to the coast).

The base was once part of the Soviet Union’s Cold-War-era nuclear deterrent. After the USSR’s dissolution, the missiles were sent to Russia and the base was decommissioned. However, one of its ten ICBM silos was preserved, along with the underground Launch Control Centre (LCC). The adjacent top-side museum has models of both:

Also in the museum was a mock-up of the command centre on level 11 underground from where the missiles would have been triggered to launch by the missileers on duty once the correct codes had been issued:

But the highlight of the visit to Pervomaisk was going down into the original LCC, in a tiny lift.

In the real command centre, which would have been staffed by two missileers and a supervising commander, our guide then started a mock missile launch sequence involving all manner of flashing lights and alarm noises, until all ten missiles (marked by that circle of ten lights towards the top) were launched … well, simulated to have been launched.

After that we headed down to level 12, the bottom-most one, via this precarious little steel ladder:

On this level was the “living quarters” for the back-up team of missileers awaiting their shift, where they had a TV, microwave, fridge and flush toilet in addition to the three beds.

Apart from everything being in Cyrillic, the LCC so far looked very much like the ones I had seen in the USA, namely the Titan II silo in Arizona and the Minuteman site in South Dakota. But the living quarters in Pervomaisk had something that I doubt you would ever have seen at any of the American counterparts – a samovar, one of the most Russian of icons! (It’s for hot water for making strong black tea.)

Back at the surface, or “top-side” as it’s known in missileer parlance, we saw, amongst other things, the concrete plate that shields the LCC beneath it.

A short walk further along we reached the lid of the one ICBM silo that has been preserved at this ex-base.

The lid was left half-open, so we could peek inside and see that the inside is now at least three-quarters flooded with water.

The site also includes various large objects in an open-air museum collection, including this missile carrier:

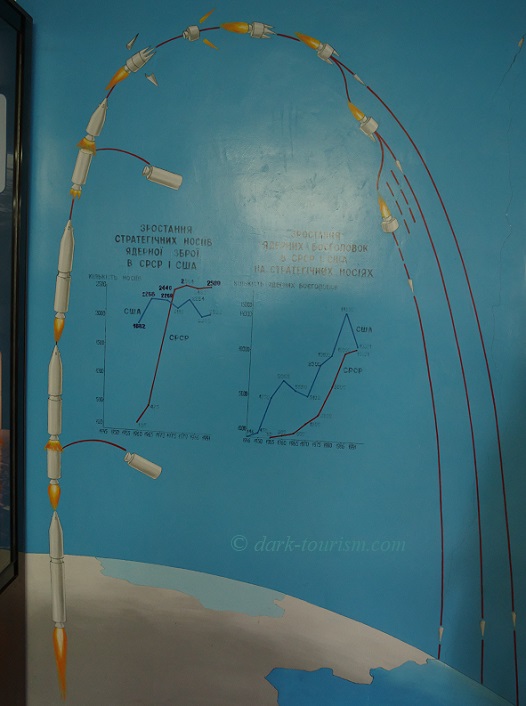

There were also various small and large missiles and other military vehicles. And inside the indoor museum exhibition I found this chart illustrating a near-complete launch trajectory of an SS-24 ICBM with its three stages and MIRV warhead (the acronym stands for ‘multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles’; in the case of the SS-24 that was three separate nuclear warheads):

The illustration stops just short of showing the mushroom clouds of the missile’s nuclear warheads. So perhaps at the moment witnesses seeing the missiles arrive would have had a wide-eyed facial expression like this dummy on display in the museum wearing an NBC hazmat suit (same as the featured photo at the top of this post):

Maybe I had a similar expression on my face on Sunday when I read about Putin’s announcement of high alert for his nuclear weapons …

.