In the first Blog post based on my summer travels through (mainly) Great Britain I indicated in my overview that Orford Ness was one of the top highlights of the trip and that it might warrant a separate Blog post of its own. It does indeed and this is that post.

I’ve already written and uploaded the full-length chapter about Orford Ness to my main website. For more detailed historical background information, my full first-hand visitor account and for all visitor practicalities please consult that chapter. Here I’ll bring you primarily a photo essay and only the bare minimum of historical information. There’s some overlap with the chapter’s photo gallery, but it’s not identical with the photos presented here.

Briefly, Orford Ness, a shingle spit off the coast of Suffolk in the south-east of England, had been a military testing and research site since just before WW1. But what makes the place most relevant to dark tourism is the legacy of its role in the Cold War as one of the main sites used by the so-called “Atomic Weapons Research Establishment” (AWRE) of the Ministry of Defence (MOD). Here all of the nuclear weapons developed by Britain were tested – not in the sense of actual nuclear tests (those were conducted in Australia, especially Maralinga, and later in the Pacific), but the weapons were subjected to all manner of “environmental” tests, i.e. heat and cold, extreme G-forces, vibrations and so on, to see if the systems survived and worked under the harsh conditions they might encounter in actual service. Even though no nuclear cores were present during the tests, the high-explosive core mantles, whose intended role is to trigger the nuclear chain reactions, were there, and so the tests ran the risk of these explosives accidentally going off, meaning considerable security measures had to be taken.

To this end, several bunker-like “laboratories” were constructed for AWRE, including two that have become known as “the Pagodas”, due to their shape with heavy concrete roofs on columns. You can make them out in the distance in this first photo, taken from the pier in the village of Orford:

.

Obviously, Orford Ness was a top-secret site and strictly off limits to ordinary people – but the villagers of Orford could still see these structures, and had an explosion occurred, they would have noticed. Fortunately that never happened, though, or at least there is no known record of any accidents.

The research facilities were closed sometime in the 1980s, and in 1992 most of the area was acquired by the National Trust (NT), who have opened the site up to the general public. You have to book ahead of time online and then take the ferry provided by the NT at your chosen time slot. Once on the Ness you are free to explore, but have to stay on the paths/tracks of the three suggested hiking trails. In the next photo you can see the Blue Trail that begins a short distance from the ferry jetty of Orford Ness:

.

At the end of that path you come to a fence that has MOD signs on it prohibiting access to the areas beyond, but on the left edge of the photo you can make out part of a building that houses the NT’s main exhibition about the history of Orford Ness.

.

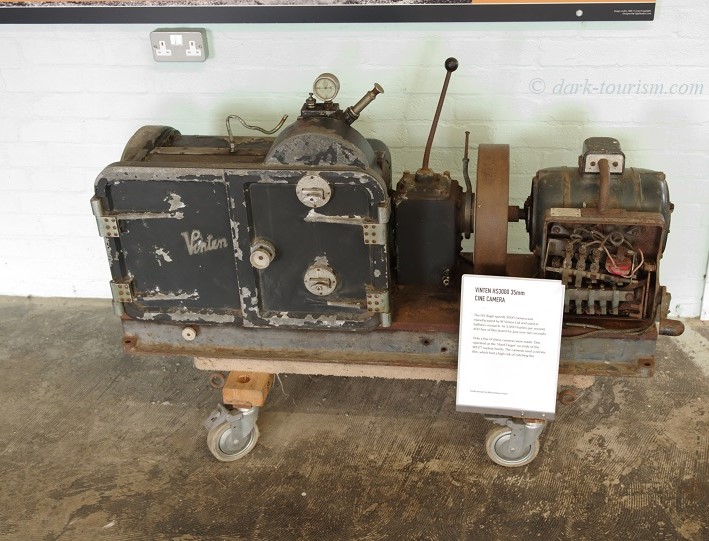

The exhibition is entitled “Island of Secrets” and features lots of information and a few remarkable artefacts on display. Amongst those are these old super-high-speed cameras that were used to record the bomb tests:

.

Also on display is a genuine bomb casing (inert, of course) of what used to be Great Britain’s main atomic bomb type until the 1990s, named prosaically WE177.

.

Outside the refurbished building that houses the exhibition there are remnants of other buildings and structures that served various functions at the test site, such as these relics:

.

A few buildings are still intact or have been refurbished, such as the one seen in this next photo:

.

Another remnant is this old petrol pump:

.

Yet another relic was this part of some high-voltage electrical device, with a warning sign still in situ:

.

Eventually you come to a newer bridge called Bailey Bridge that takes you across the body of water known as Stony Ditch that separates the marshland area of Orford Ness from its shingle part:

.

And here’s a view from the bridge over Stony Ditch and the AWRE laboratories in the background:

.

The first building you come to after crossing the bridge is this one:

.

This so-called “Bomb Ballistic Building”, which dates back to 1933, was primarily used for recording bomb tests with high-speed cameras (also later during the AWRE era). The green steel casing you can see on the roof housed such camera equipment. Today the interior of the building features an extra exhibition about the military years of Orford Ness.

From the roof you get good views over the surrounding area, and can spot this mysterious circular structure that is ca. 50m in diameter (same photo as the featured one at the top of this post):

.

What this structure was for is indeed still unknown – as the NT’s exhibition says, “Orford Ness still keeps some of its secrets”. One speculation is that it may have been the base of some prototype radar installation (see also below).

There are plenty of other mysterious relics to be spotted, such as this concrete block with iron hooks on it (also possibly for supporting stabilization ropes for some radar tower or something):

.

Rather mysterious are also remnants of cables in ceramic tubes, such as these:

.

The area beyond the Bomb Ballistic Building is the main part of the ‘vegetated shingle’, which is a very rare environment (Orford Ness features some 15% of this that exists worldwide). It’s also very delicate, hence it is protected. Footprints would leave damage that would take many decades to heal. This area is however home to a population of rather large hares. From the observation platform I saw a pair of hares play-fighting on the shingle. Another hare, standing up, can be spotted in this (cropped) photo on the right edge of the frame:

.

The building seen in the background is the former Coastguard lookout, which is now deserted and crumbling. Next to it used to stand a lighthouse, but coastal erosion threatened to topple it, so the structure was dismantled in 2020. Access to the track leading there is prohibited, though:

.

In fact you have to stay on the prescribed paths and tracks, not only for reasons of environmental protection, but also because of the danger of UXO (unexploded ordnance) that may still be in the ground from the bomb tests especially during WWII, despite years of work by the Explosive Ordnance Disposal units of the RAF in the 1980s.

Following the path further you come to another building that is also a mysterious structure, and is called the Black Beacon:

.

The Black Beacon was constructed in 1928 and was used for experimental research into what later became known as “Radar”. It was in fact here at Orford Ness that the first working radar installations were developed in the 1930s that shortly afterwards (under the name of “Home Chain”) would prove so instrumental in the UK’s victory in the Battle of Britain against the Nazi German Luftwaffe in 1940.

Around the Black Beacon you can also see the foundations of a number of buildings that were used in the AWRE years but were demolished because they had become dangerously dilapidated. Next to the Beacon still stands a “Power House” that used to house generators for the prototype radar installation … and in front of it is yet another mysterious circular concrete structure:

.

The interior of the Black Beacon houses yet another extra exhibition and from the upstairs windows you get a good view of the AWRE laboratories:

.

Following the path further you come to what was the “Hard Target Impact” testing facility:

.

Here, bombs like the WE177 were driven on a rocket-propelled sledge into a high-density concrete wall, seen here on the right, to determine if the bomb casing and the components inside could survive such an impact intact. This was required to enable so-called “laydown” deployment of nuclear weapons whereby the device was not set up in the air or on ground impact but by a time-delay fuse so that delivering bombers would get enough time to safely fly away from the blast zone before the bomb went off. Also to be seen in this photo are the remains of a steel lattice tower – on which high-speed cameras were mounted for recording the impact tests.

Next to the Hard Target Impact facility is the Control Room for first AWRE Lab 1 and later the impact tests – but this is no longer open to the public.

At the end of the publicly accessible path you finally come to what was AWRE Laboratory No. 1:

.

The interior of this is partially accessible, and this is what you get to see inside:

.

The overgrown part beyond the big puddle of water is where Britain’s first nuclear bomb, the “Blue Danube”, as well as later devices were subjected to vibration tests. But you can only see this through a wire-mesh fence.

.

The other labs, including the two “Pagodas”, are not normally accessible as they are still owned by the MOD and are deemed unsafe for entering. They are being allowed to deteriorate (or to “ruinate”, as the NT brochure puts it) without interference and will probably collapse at some point. These days the only way (legally, that is) of getting close to these structures is by securing a space on the rare guided group tours by trailer that the NT offers. Unfortunately these tours take place only a few times a year and sell out far in advance. I tried but failed to secure a space on the tour when I visited. Maybe I should try again some other time and then plan further ahead …

Another structure that is sadly inaccessible to the public is the “Cobra Mist” building, seen here in the distance:

.

“Cobra Mist” was the code name for an ambitious over-the-horizon (OTH) radar installation constructed and tested by the UK and the USA in collaboration. It became operational in 1971 but despite being able to reach deep into the Eastern Bloc was discontinued (for various reasons explained here). It was a Western equivalent of the fabled Soviet-era Duga installation in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

The Cobra Mist site was later used by radio stations (including for many years the BBC World Service). It is currently in private hands and hence off limits. Only the original main building, which was built on stilts as a flood-protection measure, still stands. The radio pylons you see in the photo above are newer. The original array was dismantled. You can find only a few remnants by the tracks that form the Green Trail (which is open only part of the year, outside the bird breeding season).

Despite some parts being inaccessible, I found Orford Ness a very worthwhile element of my wide-ranging itinerary this summer. In fact I felt that an almost magical aura and at times mystique made this visit very special indeed. I hope that in this Blog post (and the corresponding main DT website’s chapter) I have managed to convey that at least to some degree.

2 responses

Hi Peter,

Really enjoyed this – and learnt alot, despite having visited several times! My family holidays in Aldeburgh just up the coast, and so I spent many summer days sailing on the Alde and speculating on the origins of the mysterious radio towers to our south. In those days, you couldn’t visit the Ness, but could obviously see the structures from Orford and landing finally, in around 1996, was pretty exciting. Subsequently, taking my own boys back I really appreciated it and also love the remote otherworldliness of the whole area – Shingle Street, with it’s single terraced row of houses is as a magnificently and beautifully bleak a place as you will find during the winter especially. A big shame for me was being unable to visit during the winter when the area takes on a whole different tone. But fully understandable given the importance of the area for wildlife.

Thanks as ever Peter,

Sam

Hi Sam,

thanks for the comment – I had’t realized you had such close ties to that part of the country!

cheers,

Peter