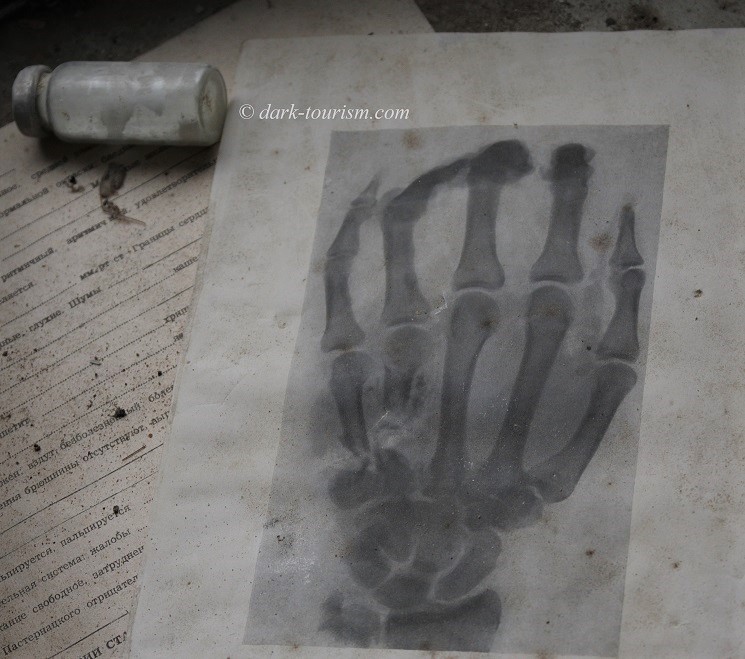

To make up for last week’s absence of a new blog post (and the likelihood of there not being one next week), I give you an extra-elaborate one today – on a medical theme, not decided on by a readers’ poll, but just by myself. The reason being that early tomorrow morning I’ll have my left hand operated on. Hence I picked the above photo as the lead image.

I took that in an abandoned hospital in the ghost town of Pripyat in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. It was a chance find, but seems fitting. The X-ray image shows some damage on the base of the ring finger – precisely where my problem is (so-called ‘trigger finger’). What a coincidence!

Exploring the hospital in Pripyat was generally fascinating. There is something about abandoned hospitals – maybe because normally, when not abandoned, there is always some activity going on, day and night, and lots of people are about. So seeing a hospital ward silent and without any people, is a maximum contrast to the normal state of things. Here’s another photo from the same hospital:

As you can see there are even some boxes with meds in this glass cabinet still in situ. I couldn’t work out what they were, though.

One of my favourite photos from this hospital is this next one, taken in the maternity ward:

These two rows of empty baby cots are extremely atmospheric, I find, again probably because of the silence and emptiness contrasting so with what an in-use room like this would normally be like. I also like the colours, the red rust of the cots against the peeling pale bluish-green wall (why is that sort of colour so typical of hospitals?).

But dark tourism also overlaps with medical aspects in quite different and more direct ways, especially in medical museums/exhibitions. The most talked about such exhibition must be the travelling Body Worlds display of plastinated real bodies (or parts of). But icky medical displays have a long history. Even three centuries ago or so, complex 3-D wax models were often made of certain conditions and body parts. These collections were primarily intended for study and teaching, but some were also open to the general public. One of the oldest such collections is the one inside the Palazzo Poggi in Bologna in Italy, which is where I found this remarkable piece:

This gives the phrase “picking somebody’s brain” a whole new meaning, doesn’t it? Hannibal Lecter style … Also at the Palazzo Poggi, which is part of the medical university of Bologna, I saw this semi-dissected “sleeping beauty”:

The early Italian wax model collections, where this technique was pioneered, inspired others too, such as the Habsburg Emperor Joseph II of Austria, who promoted all manner of enlightenment measures. One was equipping the medical university of Vienna with its own collection of wax models. This was duly named after the Emperor: “Josephinum”! Many of the models included in its collection are truly remarkable in their detailed accuracy; real works of art. Some display bodies in ways you could never see them in real life, such as this expressive male body minus skin but with all blood vessels, nerves, ligaments, etc. intact (and with wide open eyes, which makes it doubly spooky!):

Medical museums are a distinct sub-category of dark tourism and there are numerous ones in the world, including the excellent Paul Stradins Museum of the History of Medicine in Riga, Latvia, where I saw this exhibit:

This could perhaps be called “before the tonsillectomy”. Anyway, the poor dummy kid strapped to the chair and mouth held open by those metal clasps is rather a brutal image.

The next photo may be brutal for some too, especially if they are smokers. This is also a display at the same medical museum in Riga, namely of two jars with pickled lungs in formaldehyde, left a healthy non-smoker’s lung, right a blackened smoker’s lung:

It’s not only when seeing things like this that I am so glad that I kicked my own smoking addiction over two decades ago. This means that I’ve been a non-smoker much longer than I used to be a smoker (not counting the time before I’d become one). I won’t ever say, though, that giving up smoking is easy. It’s not. I found it took much more willpower than I had anticipated and it also took a lot longer to really get over it for good. When they say, oh, it takes only two weeks or so for the body to get over the physical addiction and you will feel so much better and fitter, then that’s not really correct. At least not in my case. I did not feel better or fitter in such a short period of time. In fact at first the coughing got even worse. Moreover, while the direct nicotine craving effects may subside within a few weeks, the psychological craving didn’t stop so soon but instead lasted disproportionately longer (a few years, to be perfectly honest) and was only very gradually fading. That’s presumably why so many people relapse so easily. But for a long time now I’ve felt safe from that risk, and I’m really glad about that. It was an effort, but worth it. It helped that at the time (in the late 1990s/early 2000s) I was still living in Britain – when anti-smoking campaigns were gathering momentum, rules were being tightened, and people would tut-tut at you as they walked past and spotted you having a smoke outside. Now I’m grateful to them for it! Being increasingly ostracized as a smoker in Britain certainly helped me reach that moment of quitting. That may have been different had I already been living in Austria, which is only now slowly catching up with most of the rest of Europe in this regard (and much more reluctantly). Until not very long ago, almost all restaurants and bars in Austria had smoking sections or were entirely smoking! The stink of cigarette smoke was almost inescapable. Thankfully that has now changed.

Thinking of pickled body parts in jars made me remember this brain specimen in formaldehyde that I spotted in a school’s biology classroom in Pyongyang, North Korea:

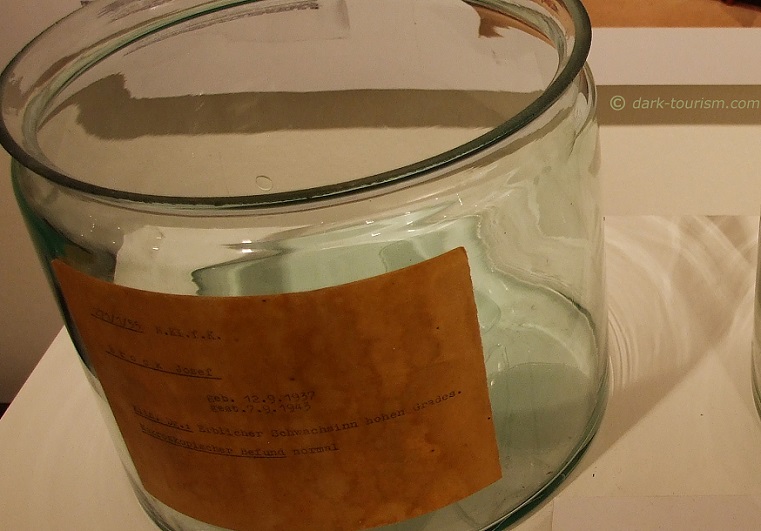

Thinking of pickled brains also made me remember the display of this empty brain-pickling jar displayed at a museum at the “Spiegelgrund” hospital complex in Vienna:

The Spiegelgrund was/is a wing at the large psychiatric hospital complex called Steinhof, located on the edge of Vienna. After the Anschluss/annexation of Austria by Germany in 1938, the hospital became one of the places where the Nazis carried out some of their medical crimes, including the so-called “euthanasia” programme, based on the Nazis’ crude interpretation of “eugenics”. And so it came that countless people, including many children, who the Nazi doctors deemed “useless” ended up here, shut away, subjected to cruel medical “experiments”, or left so neglected that they starved. Some 7500 people are believed to have lost their lives through these crimes at (or through) Steinhof. Many others were sterilized. Most survivors were left traumatized. But the perpetrators, as so often, largely got away with it. It’s hard to believe, but some of the “specimens” collected from patients during these medical crimes were still in use for research up until the 1980s (they were later buried in a special section at the Vienna Central Cemetery), probably including the brains that these jars once contained. They are now part of a special museum at the Spiegelgrund about this very dark chapter of history.

Of course, the Nazis committed more than just medical crimes behind closed hospital doors, but also had dedicated killing centres for their “euthanasia” programme, which were in many ways the precursors of the death camps established during the Holocaust, and even some of the staff were the same people. Medical “experiments” were also conducted at several concentration camps. And a common method of killing subjects was an injection of phenol straight into the heart. This is a syringe used in that way, on display at the camp memorial of Mauthausen:

The medical departments at the concentration camps typically also had dissection rooms, such as this one at Sachsenhausen:

But the Nazis’ dodgy use of the medical “art” didn’t only affect their victims. Even their own soldiers were medically manipulated to “perform” better and longer in battle. The key brand name to mention here is Pervitin. Here’s a display of a packet and two small tubes of pills of the drug on display at the Deutsches Technikmuseum in Berlin:

Pervitin is a stimulant drug that the Nazis used to keep Luftwaffe pilots alert during long night-time bombing raids in the Blitz, for example. It was also used by the Wehrmacht (army), where it was nicknamed “Panzerschokolade” (‘tank chocolate’). The agent in the pills is methamphetamine, better known today as “crystal meth”! Initially it seemed to be the ideal war drug: it stopped tiredness and made the user alert and euphoric … and forget the danger to their life in war. The speed with which the Wehrmacht conquered Poland and France is largely attributable to Pervitin, much more so than to any alleged mental superiority or bravery. It was literally Nazis on Speed!

But beyond making Blitzkrieg faster and more efficient, the mass use of such a drug in the military was of course not so ideal in the longer term. Apart from being addictive it also caused side effects such as psychosis, impaired judgement, aggression, and depression in the longer run. It could be deadly, too, e.g. through heart failure or suicide … Hence health officials in the Third Reich called for limiting the use of the drug or even withdrawing it altogether. Distribution was indeed cut back from 1940, but it kept being rolled out by the Temmlerwerke pharmaceutical plant in Berlin. 35 million doses were produced during the war. And it didn’t stop after the war. Production continued. Apparently it wasn’t until the late 1980s that the drug was finally taken out of the GDR’s military’s medical stock. Still today many militaries around the world (including the USA) make use of performance-enhancing drugs, but methamphetamine is now mainly a “recreational drug” (and illegal in many parts of the world).

Some medical drugs can also have unintended/unexpected side effects that can be devastating. A well-known case was that of thalidomide, a sleeping pill that when taken by pregnant women to combat morning sickness caused widespread birth defects, mainly in the late 1950s and early 60s. In Germany the drug was marketed under the name “Contergan”, and children with malformed limbs as a result of this drug were later commonly referred to as “Contergan-Kinder”. The scandal this caused is one of the many topics at the Haus der Geschichte history museum in Bonn, Germany, where there is this display case with packets of the drug that caused so much misery:

Not far from Bonn, just outside Ahrweiler, is the Marienthal government relocation facility, a Cold-War-era bunker to provide shelter for the FRG government and support staff in the event of nuclear war … except that by the time the bunker was completed, the era of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles had begun, reducing the forewarning time to only half an hour, hardly enough for moving a few hundred people all the way from the then West German capital and seat of government, Bonn, which even under ideal traffic conditions on today’s Autobahn (motorway) is at least half an hour’s drive away. Still the bunker was kept in working order until the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s. Most of the bunker was then gutted but one stretch was kept and turned into a kind of museum and opened to the public (on guided tours only). The bunker featured dorms (and single rooms for the president and chancellor), supplies, decontamination chambers, a communication centre, etc., and: a medical centre. Part of this was this dentist’s practice:

For many, the thought of going to the dentist is dark enough, but of course it’s the Cold-War association that makes this bunker practice a proper dark-tourism attraction. And it gets darker on the medical side too. On top of some meds supplies cabinet next door I spotted these two orange boxes:

These contained emergency medical gear in case someone in the bunker needed to have a limb chopped off or a tube inserted into the throat to be put on a ventilator. Not nice thoughts.

Somewhat less grim but also not nice is the thought of infestations with bodily creepy-crawlies like fleas and lice. To combat those, the USA sent tins with insecticide as part of their C.A.R.E. (Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe) packets sent to Europe in the aftermath of WWII, when people were starving and sanitation was limited as a result of the war. This is an exhibit at the Allied Museum in Berlin:

And finally, thinking of parasites, a unique sort of medical museum is the Meguro Parasitological Museum in Tokyo, Japan. Among its many icky exhibits is this tapeworm, removed from an unlucky human’s intestines:

This specimen, preserved and illuminated in eerie blue light, is a whopping 29 feet long (8.8m). To get that across there was a fabric tape next to the specimen of the same length which you could unroll to get an impression of just how long that is.

But with that I shall release you from the world of icky medical dark-tourism attractions. I hope my op tomorrow won’t be so icky, nor too painful. It’s only an outpatient procedure performed under local anaesthetic, but it might be uncomfortable for a couple of weeks afterwards. Let’s see how I get on, and whether I can type. If typing is not really an option, and this blog consequently has to take a little hiatus, then at least you know why.

[Note: some of the photos and certain stretches of text above were taken and adapted from my archive of ex-posts on my former (purged) DT Facebook Page.]

4 responses

Great read Peter. I love WW2 history. Then again, I love all history. How long ago did you do Pripyat? I would love to do it but nervous about radiation. I hope your hand op was a success.

thanks! I’ve been to Pripyat three times, in 2006, 2015 and 2018. Radiation is no real danger any longer, except at a few hotspots. But even at those, as long as you keep your time spent there reasonably short, it is fine. You get more radiation exposure during a CT scan or a transatlantic flight than you do during a day or two in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Whether the hand op was a success remains to be seen over the course of the next week or two. I do hope so.

Thanks for the reply Peter. I might get to Pripyat yet. Take Care !!!

When you do plan to go, contact me first, I can give some recommendations. By no means go on one of the relatively cheap group day tours by coach. Being in a large boisterous group totally destroys the ghost town atmosphere that is so crucial about Pripyat. Rather save up and invest in a two-day private tour, or put together a very small group to share costs. I can pass you on to a very competent, trusted private guide.