Long promised (e.g. here) and now finally here it is: a Blog post about the other big “T” that dominates Belfast’s tourism portfolio (the other being the Titanic, of course), which is more dominated by sites that fall under the heading of dark tourism than in any other city I know (well, perhaps with the exception of Berlin, the “capital” of dark tourism, by the number of sites alone).

I won’t go much into the historical background of the Northern Ireland conflict (aka “the Troubles”) here – for that please refer to my main website’s Northern Ireland chapters, in particular those for West Belfast.

For many tourists visiting Belfast, the main “Troubles”-related activity is those (in)famous Black Taxi Tours – which is exactly what I did on my first trip to the city back in 2012. On my more recent and much longer return trip in April this year I instead chose a walking tour of West Belfast and also did a lot of exploring independently.

A major spot on any “Troubles”-related tour (whether guided or unguided and whether on foot, by taxi or by coach) is the so-called Solidarity Wall (also International Wall). This is actually the outer side of the perimeter wall around an industrial complex (a flour mill) on the corner of Northumberland Street and Divis Street, the latter being the eastern extension of Falls Road, the main thoroughfare through the Republican part of West Belfast. There are dozens of more or less political murals on this wall, many in solidarity with parties to other conflicts worldwide (hence the name), others more focused on the local history. Here’s just a small sample:

Of these two murals one celebrates the Falls Commemoration Committee, the other is basically another call for Northern Ireland’s unification with the Republic of Ireland, which had always been a major goal of the IRA and Catholic Nationalists in general. The person depicted in the mural waving a flag is Bobby Sands, one of the key Republicans and one of those who died in a protest hunger strike at the Maze prison in 1981.

The murals on the International Wall are in constant flux, by the way. A few are kept for longer, but many are repainted with some regularity, so if you go on a repeat tour some years apart (as I did in 2012 and 2023) you will not see much that is familiar from the previous occasion.

Another key stop on practically every tour of West Belfast is the so-called Peace Wall (also known as the Peace Line). This is actually a separation wall between the Republican and the Unionist sides. Most visitors get to see the Peace Wall from the Unionist side along Cupar Way in the Shankill district, which is also where there are not only murals and graffiti, but many visitors also are encouraged to leave little messages on the wall, even though a sign asks you not to do so. Fortunately on both occasions I was there my guides did not urge me or any other participants in the tour to engage in this somewhat dubious “tradition”.

On the other side of the Peace Wall in the Republican Falls Road district is something more interesting from a dark perspective: Bombay Street, the spot where the “Troubles” first turned civil-war-like, namely in August 1969 when Unionists attacked the street and its Republican residents, killing several, and houses were set on fire. Hence the incident is sometimes described as a “pogrom”.

The rebuilt terraced houses on the north side of Bombay Street facing the Peace Wall have their rear windows and back gardens protected by a kind of metal cage – against “missiles” (like bottles or stones) coming over the wall from the other side. I found that a most depressing sight to behold and testament that, despite the Peace Process and the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, the conflict is far from resolved but still simmering away under the surface.

Here’s a photo of the south-eastern end of Bombay Street taken from Kashmir Road with the Peace Wall and the cages over the rear of the houses visible, as well as a poster on the side wall of the terraced houses commemorating the events of August 1969 here in Clonard (the name of the district that Bombay Street is in):

It’s been said on several occasions (including in my 2012 Ireland guidebook) that somehow the Republican side manages to get their side’s story across to foreigners better than the Unionists do and I’d concur with that observation. One reason other than the famousness of the Solidarity Wall and other Falls Road murals may also be the Irish Republican History Museum just off Falls Road, housed in a former textile mill. One section has a strong focus on the imprisonment of Republicans (often without trial!) and one remarkable artefact, in between models of the H-blocks of the Maze prison, is a fragment of the actual perimeter wall of that prison (which was closed in the year 2000 and subsequently partially demolished):

Amongst the other exhibits at the Irish Republican History Museum are also several decommissioned weapons used by the IRA in their armed struggle, including these automatic guns (same photo as the featured one at the top of this post):

Towards the western end of Falls Road lies Milltown Cemetery. This has long had strong Republican associations and there are two ‘Republican Plots’. The newer, bigger and better known one is that where e.g. the ten hunger strikers of 1981 who died in their protest are buried, including Bobby Sands. The earlier Republican plot and its “County Antrim Memorial” is another Nationalist hotspot here (note the Irish flag flying) and 34 IRA members who were killed “in action” in the 1960s and early 70s lie buried here:

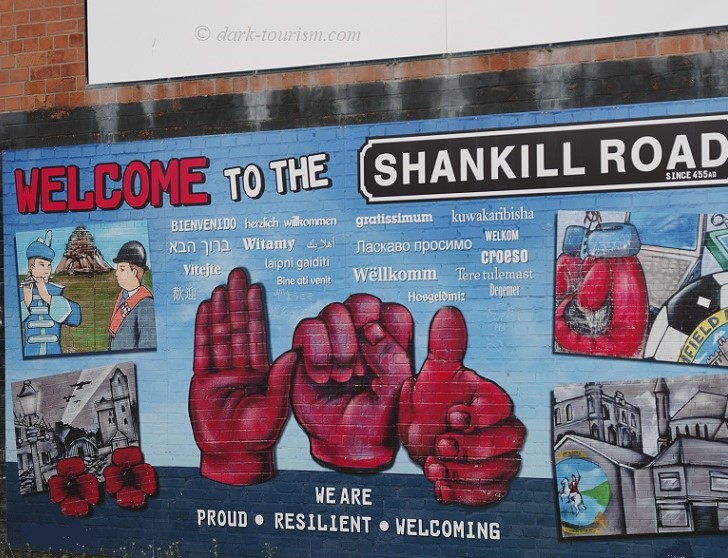

But now over to the Unionist side. Shankill Road is to the Unionist side what Falls Road is to the Republicans, both as the main thoroughfare through the Shankill district and as a historic site. As on Falls Road, older political murals have been joined by more welcoming and in part reconciliatory ones. Here’s an example:

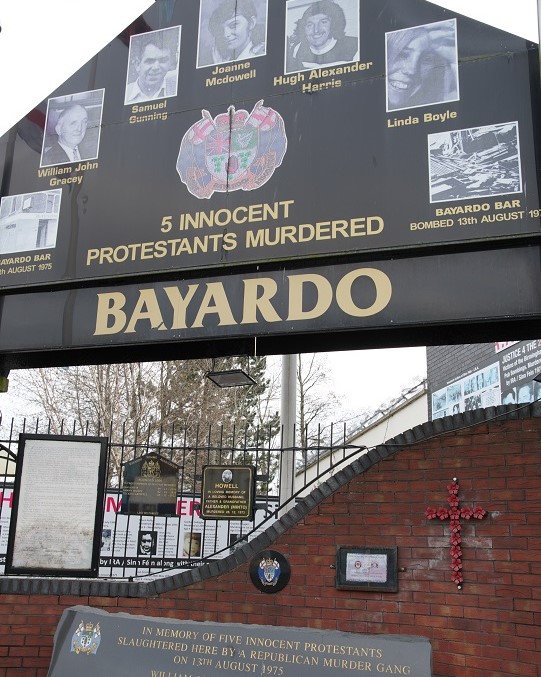

A bit further down the road, however, is the Bayardo memorial. This commemorates the IRA attack on the Bayardo Bar on Shankill Road in 1975, in which five people were killed. While the official monument is comparatively restrained, the “wild” memorial plaques and text-and-photo panels detail Republican atrocities, perpetrators and associates in extremely confrontational words without a hint of reconciliation. One equates “IRA, Sinn Fein, ISIS – no difference”, another personally rails against “Phoney Tony” (Blair), Ken Livingstone, Jeremy Corbyn and of course Gerry Adams. I’ll rather give you a photo of the main monument with the Unionist extreme panels not visible:

South of the Shankill Road, between Crumlin Road Gaol (see below) and Falls Road is a housing estate that features a large number of Unionist political murals, some glorifying certain UVF and UDA members, whereas some newer ones are more reconciliatory. And here’s a rather elaborate one commemorating the summer of 1969, when the outbreak of violence reached its first major peak and is often seen as the beginning of the “Troubles”:

Back on the Shankill Road I also spotted expressions of the Royalist aspect of Unionism, whose goal has always been an adherence to Northern Ireland remaining part of the UK and reverence for its monarchy. Here’s a mural with a fond commemoration of the late Queen Elizabeth II:

The Shankill district is not the only Unionist part of Belfast. Almost all of East Belfast is also deeply Unionist (apart from a couple of small Catholic enclaves). The main thoroughfare going through these parts of the city east of the River Lagan is called Newtownards Road. And it’s here that you can find many more Unionist murals, again some reconciliatory, others still staunchly martial in style. Here’s an example of the latter, depicting three masked and uniformed UVF fighters with machine guns and hand grenades in “war action”:

Interestingly (and ironically (?) there is a small poster on the wall beneath the mural that says “the possibility of a return to violence is very real”. Again there’s evidence of the fact that the underlying roots of the conflict have not really gone away … and it may one day be rekindled again.

The “Troubles” was a conflict not only between Unionist and Republican factions and their paramilitary organizations, but there was also a “third party” as it were: the police and the British Army. Although it has to be said that the original RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) was predominantly (almost exclusively) Protestant and hence more on the Unionist side and anti-Republican, and the British Army, deployed early in the “Troubles”, was obviously also there primarily to defend Northern Ireland against the IRA and make sure the province remained British. Hence both the RUC and the Army were considered legitimate targets by the IRA. Yet the military presence and at times heavy-handed approach by the British (not just on Bloody Sunday) brought the IRA many extra members and sympathizers.

The military presence was also very visible, with armed soldiers and military vehicles on the streets. The police also used armoured cars, and one of those is on open-air display at Crumlin Road Gaol (which is now a museum):

Such vehicles are also still around to this day, even though the RUC was in 2001 dissolved, or rather renamed ‘Police Service of Northern Ireland’ (PSNI). I spotted this vehicle looking rather similar to the one pictured above on one of the main streets in Belfast (Ann Street, to be precise):

But with this, I shall bring this post to a close.

As this is very likely the last post of the year let me also sign off by wishing all readers a good festive season and a Happy New Year. I’ll be back with new posts in 2024. Promise!