Our latest theme poll had a clear winner so today I give you the requested one of broken glass (DT & bullet holes came second, and I may field that again in a future theme poll).

The photo above is what I consider one of the most appealing images of broken glass in my archives. It’s a close-up of a large war ruin I discovered in Mostar, Bosnia & Herzegovina, in 2009. Here’s a wide shot showing more of the same building:

This was formerly a bank building and the state it was in when I saw it back then I found absolutely fascinating, with its own characterful aesthetics, almost like an accidental work of art. I’ve meanwhile learned, though, that unfortunately all the glass, metal and insulation has been removed and only the raw concrete shell of the building remains, heavily graffitied.

The next example of broken glass is less dramatic but also has a nice array of colours. This was taken at the abandoned Taj Mahal palace in Bhopal, India:

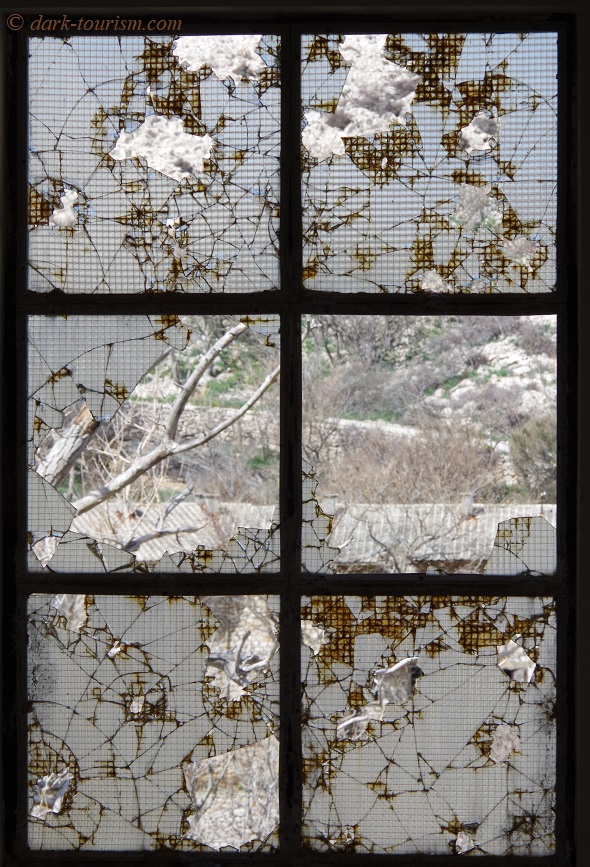

Back in the Balkans, this was a window with broken glass I saw on Goli Otok in Croatia in 2018 – and I find it especially beautiful. It looks almost like a painting:

Goli Otok was what is sometimes referred to as “Croatia’s Alcatraz”, a prison island, originally set up for housing political prisoners during the early years of communist Yugoslavia, and also known as “Tito’s Gulag”, later it was used more for regular criminals who had to do forced labour on the island (e.g. making furniture).

Next we turn to the real Alcatraz, that most legendary of prison islands, located in the Bay of San Francisco, USA. When I visited that place in the summer of 2015, there was an extra temporary exhibition on in an ancillary building next to the main cell block that was on the subject of old-age prisoners living out their days incarcerated without much (or any) hope of ever seeing the free world again. The exhibition featured large blow-up photo portraits of such prisoners, and I photographed one through a broken window. It looks like the prisoner is peaking through one of the broken holes in the glass. I find it quite a melancholy image:

Sometimes broken glass takes on shapes that can be interpreted as something else, such as this one that I spotted in Beelitz, Germany:

I immediately saw the silhouette of a howling wolf in this – can you see it too? And this next one, taken at Petrova Gora, Croatia, to me looks a bit like a seated soldier with a steel helmet and a rifle, on guard:

This brings me to the next photo, which features a real soldier with a real rifle behind a window with broken glass in the foreground:

This was taken at the abandoned ruin of a former lodge inside Awash National Park in the centre of Ethiopia on my last overseas trip before the pandemic in January 2020. In actual fact, the man seen in this photo isn’t really a soldier, but a guard and park ranger. But his fatigues make him look like a soldier. This is actually quite a common sight in gun-saturated Ethiopia …

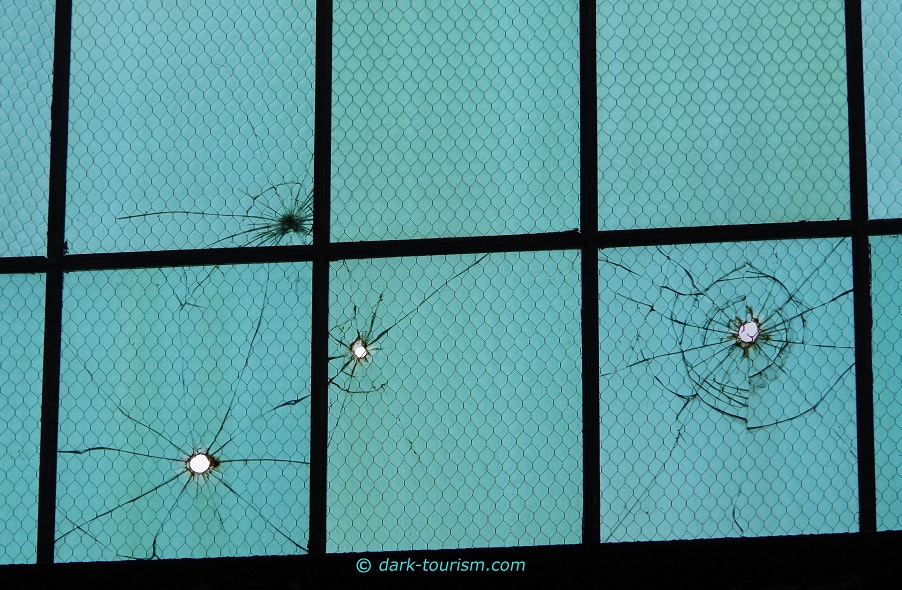

This next photo shows the effects of guns, in the form of bullet holes (yes, the same image would also have featured in a bullet-holes themed post), which in this case created another rather aesthetically intriguing image:

These bullet holes are actually quite historic: they are traces of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and can now be seen as part of a visit to the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum on Ford island, O’ahu, Hawaii.

Broken glass is regularly encountered when engaging in ‘urban exploration’ (or ‘urbex’ for short), i.e. “infiltrating” abandoned and/or forbidden buildings/structures – and one of the best places for doing this is Pripyat in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine. Here’s an example:

This was taken inside an abandoned barbershop in Pripyat. That was on my third trip to Chernobyl, that time in November 2018 when I went with a journalist of the reputed German news magazine “Der Spiegel” (external link, opens in a new tab) who then wrote a piece about me and dark tourism.

Also on that trip, in winter, we visited the kindergarten in Kopachi, one of the villages closest to the nuclear power station where the 1986 Chernobyl disaster happened. Hence almost all buildings were bulldozed and buried in the ground. Only the kindergarten and a war memorial next door remain standing. This is a view out of a broken rear window into the snowy forest beyond:

My Easter 2018 trip to Croatia also included lots of ‘urbexing’, and among other things I visited the abandoned Villa Izvor, formerly one of the grandest of the various residences Yugoslavia’s leader Tito had. This one is near Plitvice and is pretty trashed by now, but still an intriguing sight to behold. Here’s one photo – involving the obligatory broken glass:

More ‘urbexing’ was also part of my October 2015 trip to Slovakia, for instance at the abandoned spa and sanatorium complex of Korytnica, where I took this photo:

You have to wonder how that long piece of broken glass in the middle section can possibly have stayed upright, but there you are. I also like this photo because of the reflections on the glass. Another example of that is this image:

This was taken at the largely abandoned and war damaged shoe factory of Borovo north of Vukovar, eastern Croatia. And while this image has atmospheric reflections of trees in it, the final photo has no reflections at all, since the glass is simply too dirty:

But despite the absence of beautiful reflections I love the aesthetics of the arrangement of almost totally broken at the bottom, stages of less brokenness in the middle sections to completely unbroken at the top – and the completely broken section without any glass in the bottom right corner was used by somebody (not me!) to deposit an empty drinks bottle in it, which adds an odd touch of colour. This was taken in Gdańsk, namely in the old shipyards that have been opened to the general public and have partly been commodified by means of a series of information panels. The place is so historic mostly for its association with the Solidarność trade union and protest movement that played such a crucial roll in the fall of communism, first in Poland, then in all of Eastern Europe.

4 responses

Good blog, as always!

When I read the subject, I thought of the Auschwitz Monument in Amsterdam (Netherlands), see https://www.iamsterdam.com/en/see-and-do/things-to-do/attractions-and-sights/places-of-interest/auschwitz-monument

Best regards (from Oman)

thanks! I don’t think I’ve ever seen that monument when I was in Amsterdam (some six times or so).

You’re in Oman?!? Travelling or for work?

Although an ‘official’ term did not exist until 1996, dark tourism is not a new practice. People have been visiting sites of death and tragedy for centuries. Early examples include viewing public hangings and decapitations, or spectators at gladiatorial games in the Colosseum. Pompeii has been popular among those able to travel, almost since its tragic end in 79 AD. At the beginning of the h century, the site of the Battle of Waterloo became one of the most visited locations in the world.

and where is this quoted from? I do seem to recognize this. Or maybe it’s just because these things get quoted so often. I’d like to point out, though, that the pioneers of DT research, Lennon/Foley, who penned the first ever book on DT, would not agree, and neither do I. They (and I) see DT rooted in the modern age, roughly from the onset of mass media, so not much further back than the late 19th century. Watching public executions or gladiator games was not tourism. Peaople didn’t travel to it. It was more like a precursor to going to the cinema to watch a horror movie than it was a precursor to DT. Tourism is really a thing of the 20th century anyway. Moreover, those death-watching things are also fundamentally different from all that current DT is, which in the main is an endeavour to come to terms with history, i.e. with PAST death and tragedy.