Last Saturday I joined an exclusive guided group tour of the grand Central Cemetery (‘Zentralfriedhof’) in Vienna that took place after dark. I had visited this vast burial ground several times before and cover it extensively on my main DT website. Now I was able to add another, even literally darker element to it. On the basis of that I’ve amended my website’s entry for the cemetery a little and added a few extra photos to the photo gallery.

Here on the DT Blog I can give you a fuller report and a much more substantial photo essay – here we go:

The tour group met outside the main Gate (Tor 2), where everybody’s names were checked off against a list (you have to pre-book these tours) and we all had to sign a disclaimer (basically saying we were entering the cemetery after dark at our own risk).

Then we set off. At first it wasn’t totally dark but with a faint dark blue sky lingering at dusk.

As natural light faded the few artificial lights came into their own. There is minimal gloomy lighting along the main paths and many a grave has a little candle burning on it, usually inside a red-glass lantern, as seen in this photo (same as the featured one at the top of this post).

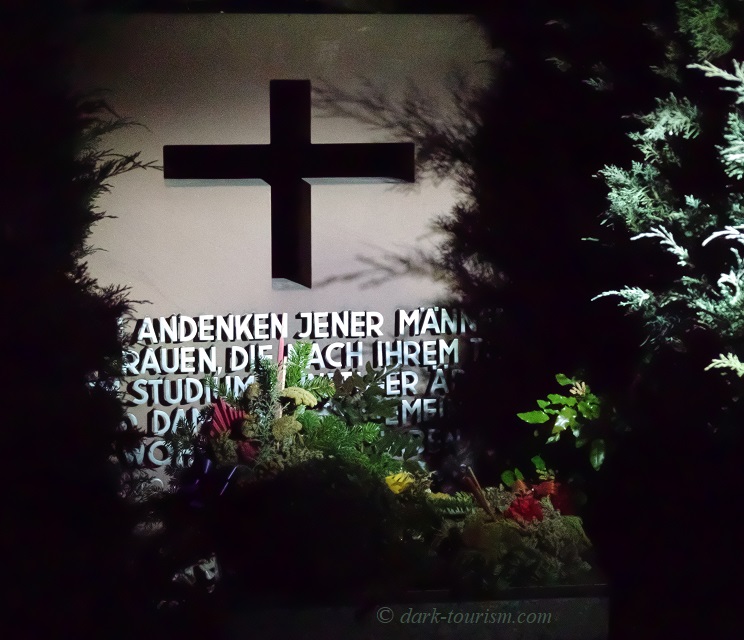

The first stop on the walking tour was by a monument that honours people who donated their dead bodies to scientific research:

There is also an “Anatomie” (‘pathology’) section in the cemetery where such bodies are eventually buried, but as that was far away from the gate, the tour did not include a visit there. Instead we headed for the central “Arkaden”, or ‘colonnades’:

The first stop there was something I hadn’t been aware of before, as it seems to be a more recent addition:

At first I misread the inscription as “World Music Hans” and thought maybe it was a reference to Falco of “Rock Me Amadeus” fame, whose real name was Hans Hölzel (and whose actual grave is located much further away in the south-eastern part of the cemetery). But then the guide made it clear that it was supposed to read “World Music Fans”. Apparently it’s a recently created tomb where people get the option of having their urns buried in closer proximity to the several music greats that are “occupants” of the Central Cemetery.

We then moved on to the other side of the colonnades, precisely to the spot of one of my favourite tombs in the whole Central Cemetery:

There are many pompous tombs in this cemetery, but this one is something else altogether: an almost Lord-of-the-Rings-like scene with two stern-looking dwarfs with shields and red lanterns “guarding” what is made to look like a mine entrance. Apparently the deceased was a mining magnate – hence the design. The actual tomb is, however, not behind the mock mine door but under the floor in front of this lavish installation.

We then left the colonnades behind – in the gloomy dark …

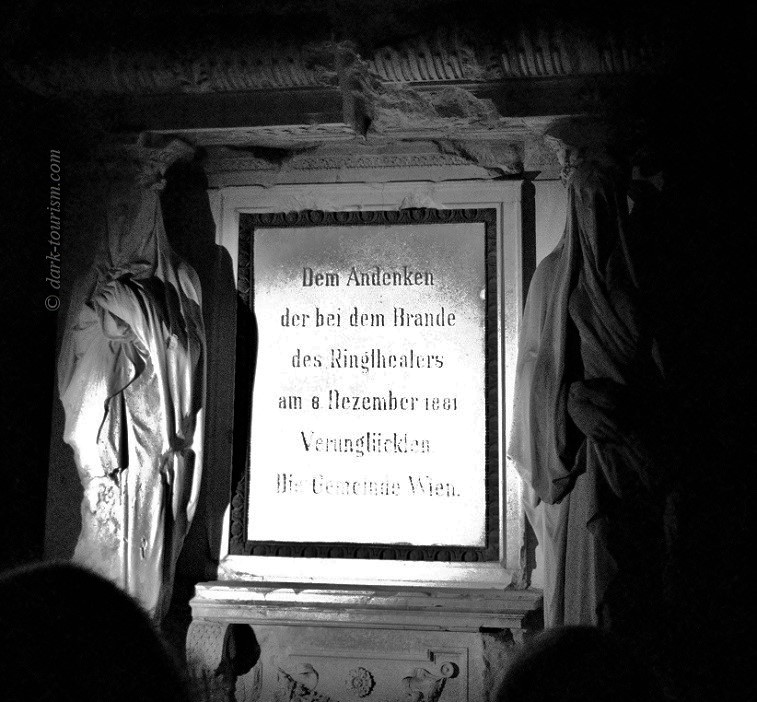

Proceeding further into the cemetery, the next stop we made was at another memorial monument, this time to the victims of a blaze at a Vienna theatre that in 1881 killed hundreds of people.

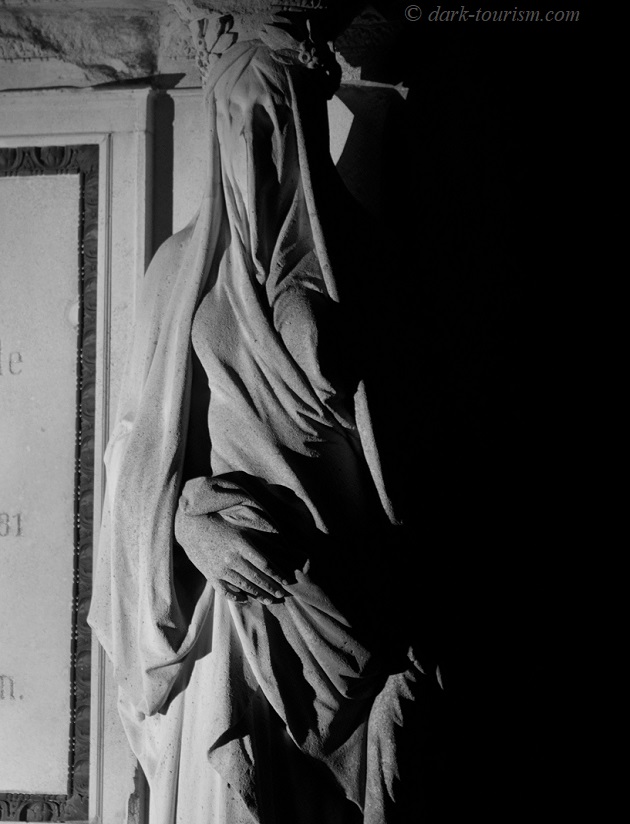

The victims’ bodies were buried here in a mass grave that was subsequently destroyed in WWII. You can still see bomb damage on one of the statues flanking the central text panel, namely on the one to the left. And here’s a photo of the figure on the right, with its classic trompe l’œil veil:

As is predictable on tours like this, quite some time was spent at graves of famous people. At the Central Cemetery there’s a whole cluster of so called “Ehrengräber” (‘honour graves’), which means that they are maintained by the state (ordinary mortals have to pay rent – or rather their families have to and usually only for a certain period of time, after which the grave plots are reused for new burials – whereas the “Ehrengräber” remain for perpetuity).

As befits a city of classical music, there are quite a few famous composers’ names represented here, from Franz Schubert to Johannes Brahms and from Arnold Schönberg to György Ligeti. Here’s a photo I took at Ludwig van Beethoven’s grave, but with the focus on the foreground:

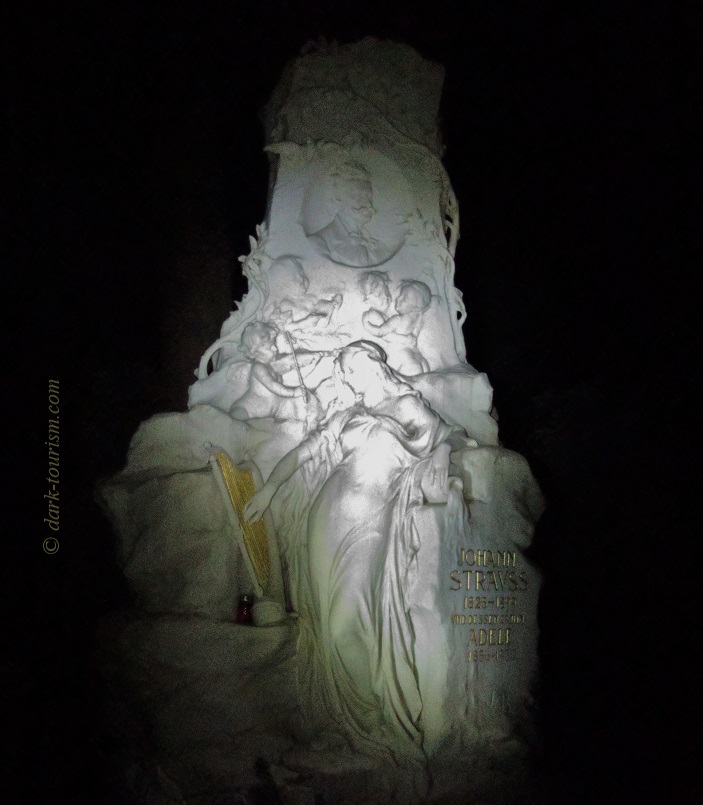

The composer name perhaps most associated with Vienna is that of Johann Strauss II, famous for his light waltzes (including “The Blue Danube”), and unsurprisingly his grave is to be found here too. As you might expect it’s quite a kitsch-laden pile:

Hidden at the top is a little bat sculpture – in allusion to another famous work of his, Die Fledermaus (‘The Flittermouse’ or ‘bat’):

Actually, there’s a sizeable population of real bats living in the Central Cemetery too, but we never saw any … nor did we encounter any of the other wildlife that this cemetery is well known for too, amongst them hares, squirrels, foxes and even deer. And speaking of elusive creatures, you could say that of this shadowy figure too:

Eventually we came to the centrepiece of the cemetery, the St. Charles Borromeo Cemetery Church (“Friedhofskirche zum heiligen Karl Borromäus” in German):

This grand Art Nouveau structure is also known under its older name Dr.-Karl-Lueger-Gedächtniskirche, or simply Luegerkirche for short. Lueger was Vienna’s mayor at the time of the construction of the church and after his death in 1910 was laid to rest in a tomb in the crypt underneath the altar.

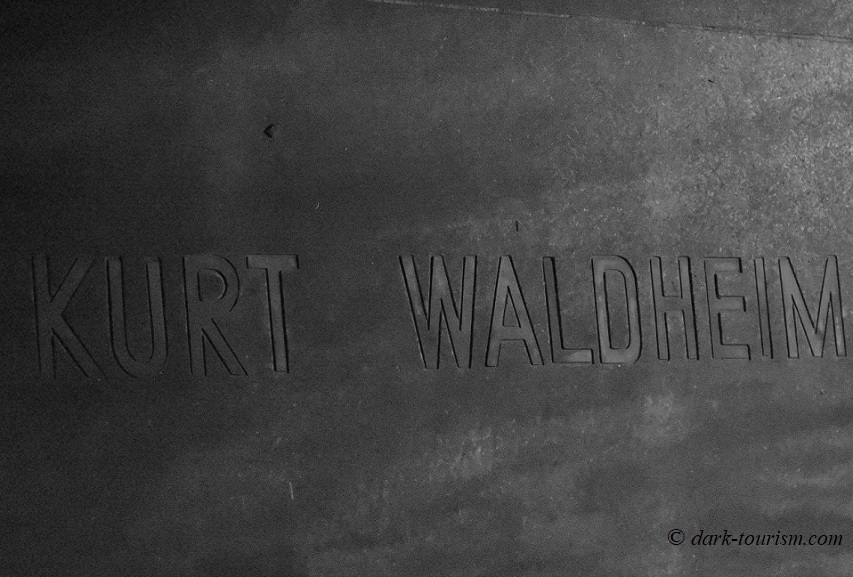

Austria’s presidents are buried outside in a special tomb cluster in front of the church. Here’s the simple slab for perhaps the most controversial president that Austria’s ever had after WWII:

Kurt Waldheim had already been Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1972 to 1981, but when he ran for president in Austria in 1986 it was revealed that Waldheim had a Nazi past that he had kept shtum about in his autobiography and during his term of office at the UN. It turned out that he had been a member of the SA in units that operated in Greece and Yugoslavia during WWII. Though no direct participation in any war crimes could be pinned to Waldheim, he was declared a “persona non grata” by the USA throughout his presidency, which ended in 1992. Waldheim didn’t run for a second term and was succeeded by Thomas Klestil, who is also buried here.

All over the cemetery you can spot little red lights – candles burning inside red-glass lanterns – which is a typical Austrian/Catholic thing. And you can also see them by the colonnades behind and flanking the central church:

We then moved on to the other side of the Luegerkirche, where I took this rather long-exposure photo:

This was actually my third attempt; the previous two went wrong: I had perched the camera on its strap and lens cap on the ground in order to stabilize it sufficiently for a long exposure and at a suitable angle, but then the camera slipped a little before the exposure was finished, resulting in this image:

It looks a bit like a cross between a double exposure and what has been called “light painting” (normally achieved by moving illuminated objects like torches through a long exposure). Sometimes even errors can by chance create appealing images …

We were then led to an area behind the church, where there is a large field of Soviet WWII graves and monuments to the “Great Patriotic War”, as WWII is known in Soviet parlance. As usual this is marked as having been from 1941 to 1945 (i.e. from the Nazi invasion of the USSR to the Third Reich’s surrender). Here’s a photo taken without a torch, relying solely on residual light (it having been a clear starry night with the moon up helped a bit):

The central part of this war-graves section is “guarded” by typical Soviet statuary, namely stern-looking soldier sculptures such as this one:

Using the powerful torch I had taken along I illuminated some of the graves, revealing the inscriptions in Cyrillic on them:

We didn’t venture any deeper into this vast cemetery, but left it at the central part where many of the famous graves are.

Most of the rest of the cemetery would have looked like this at night, i.e. mostly dark, punctuated only by those occasional red grave lights – and of course the stars:

The guide’s narration also included many a detail of Vienna’s special relationship with death, which has given rise to the saying “Der Tod muss ein Wiener sein” (‘death must be a Viennese’), and also recounted various details of Austrian sepulchral culture, many of which, however, were already familiar to me from my visits to the associated Wiener Bestattungsmuseum (‘Vienna Funeral Museum’).

Eventually we were let out of the cemetery at Gate 2 again, so we didn’t have to use the “emergency exit”. That is a door in the cemetery wall that works only one way – it has no handle on the outside – so that people who lose track of time and miss the official closing time when the gates are locked, still have a way of getting out short of trying to climb over the wall. I’ve never used this emergency exit, but its existence fostered the idea of maybe one day going back to the cemetery at dusk and deliberately staying until after closing time and then exploring the cemetery in the dark independently … But that would have to be done very discreetly …

2 responses

Very interesting! I only one morning to visit Zentralfriedhof when I was in Vienna, which of course was not enough. Would love to see it again, as well as do a night tour.

Indeed, it is so vast it requires time. Those tours always focus on the famous names, but further away are many magnificent examples to sepulchral art to be discovered. A treasure tove I will have to explore in yet more depth …