This was the other theme that in our most recent theme poll (at the bottom of this post) came second on a par with “DT & Shoes”, which was the previous post’s topic, after the winning theme, “DT & Shadows”, yielded this post.

So now for “DT & Skulls”. This is again essentially a photo essay; for more information about the various places represented here, do follow the links provided!

Skulls (and bones) are of course quite commonly encountered in dark tourism. In some categories of DT, especially ossuaries and bone chapels, they are basically what it’s all about! Here’s an example of the photos I took in what is perhaps the best-known and most visited such place, the Paris Catacombs:

.

.

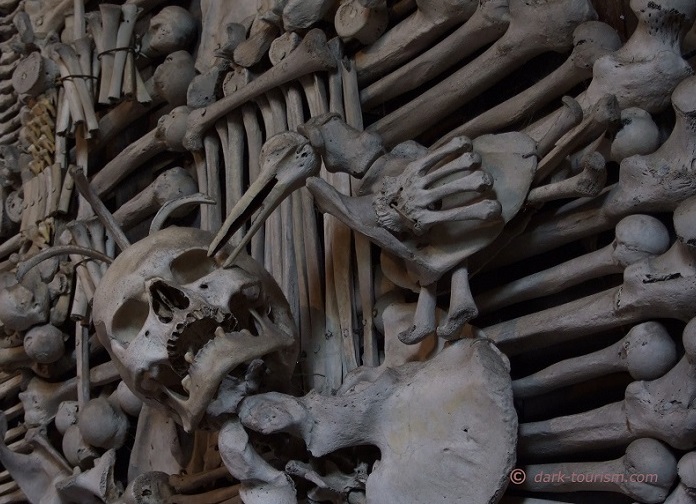

Another famous such site is the bone chapel of the Igreja de São Francisco convent in Évora in Portugal, which I visited in January this year, and where I, amongst many others, took this photo:

And here’s a photo of some framed skulls and bones behind wire mesh in another bone chapel, this time in Milan, Italy:

Not quite so artfully, but just as neatly stacked are these skulls in this ossuary in Brno in the Czech Republic:

There are countless more ossuaries in many countries, but the “mother” of them all has to be the one at Sedlec in Kutna Hora, also in the Czech Republic:

At Sedlec Ossuary most of the skulls and bones are arranged into fabulous works of art in manifold ways. This is my favourite piece:

While skulls (and all human remains) are intrinsically dark there’s an additional level of darkness if the reason for the deaths is a significant dark chapter in history. This is certainly true for WW1 and hence these skulls and bones of fallen soldiers at the huge ossuary at Douaumont in Verdun, France, can be seen as especially dark:

Another WW1 battleground of senseless slaughter was Gallipoli in 1915 in today’s Turkey. When I visited the place in 2007 (i.e. just before I started dark-tourism.com) I saw a small museum in Kabatepe, one of whose “star” exhibits was this skull with a bullet embedded in it:

In more modern times one of the darkest chapters was the (auto-)genocide in Cambodia at the hands of the Khmer Rouge regime under Pol Pot in the 1970s. At the Killing Fields of Choeung Ek outside the capital Phnom Penh stands a pagoda filled with skulls dug up from the mass graves. Here’s a close-up photo of a set of those skulls … with a bit of reflection:

Not quite as genocidal but grim enough was the “Red Terror” that the ultra-socialist Derg regime brought to Ethiopia in the 1970s. In the capital Addis Ababa a “Red Terror Museum” commemorates this brutal time and among the exhibits is this heap of victims’ skulls (same photo as the featured one at the top of this post):

Most definitely one of the worst genocides ever was the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. The various memorials commemorating this slaughter all feature amassed skulls. The Genocide Memorial at Gisozi in the capital Kigali is the one most geared towards foreign visitors (curated and run by a British NGO), and here only a selection of skulls can be seen, neatly lined up in this glass display case:

Though much smaller in scale, i.e. in absolute victim numbers (about 1% compared to the Rwandan genocide, in fact), but still classed as a genocide by the ICTY (International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia) were the Srebrenica massacres, perpetrated only a year after the Rwandan genocide, namely in July 1995. The legacy of this, the Bosnian war in general and the Siege of Sarajevo in particular have spawned a plethora of dark-tourism sites in Bosnia, where this otherwise typically rather niche section of tourism is in fact very much part of the mainstream tourism “industry”, more than almost anywhere else. I came to appreciate that a lot when I recently made a return visit to Bosnia (greatly aided by the services of the Sarajevo-based operator Funky Tours). I went to no fewer than ten war-themed museums (plus various other war-related sites) on that trip in April 2025. One of them was the Museum of War and Genocide Victims in Mostar. It’s basically a branch of the Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide in Sarajevo (along with the Siege of Sarajevo Museum), and while it is overall quite good, one artefact on display there almost made me chuckle – this one:

Look at the back of this skull – that opening is for a toilet brush. I recognized this as I have the same loo-brush holder (a kind of Halloween-like prop made of resin), also sans the brush, in my toilet at home (in Vienna). It’s not even an especially well-made model of a skull. Notice the teeth all being the same size, for example. Although you can only see half of them as the right side of the jaw has been smashed out.

When it comes to damaged skulls, none are as poignant as this one displayed at the Military History Museum in Dresden (in my view the best of its kind in the world):

This is the skull of a soldier who decided to take his own life by shooting himself through the mouth, thus taking out the central parts of his skull. Chilling to behold.

I once encountered a similarly damaged skull at the British Museum in London:

These were probably ancient skulls, but I cannot recall the exact history behind them. Similarly with this next example, displayed in a temporary exhibition augmenting the Sepulchral Museum in Kassel, Germany – involving a completely smashed-in skull:

Another partially smashed-in skull I saw at the Vučedol Culture Museum in Vukovar, Croatia:

The museum is not so dark as such, being about an ancient culture long before the modern age that my main website is based on, and it only features on my website precisely because of its often artful displays of skulls. Here’s another example, a photo that also plays with the photographic effect of bokeh (depth of field, here put back to front, as it were):

And here’s yet another example, also a photo taken at the same museum, this time putting the focus on the middle one of these three skulls:

The appearance of skulls in art is not uncommon, as I recently saw again at the Modern History Museum in Sarajevo, whose 1960s-designed staircase features mosaics with skulls like this one:

A skull famously also plays an iconic role in the famous “to be or not to be” scene in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. I was reminded of that, somehow, when I saw this display in a curio shop window in Milan, Italy, except that the “Hamlet” in this scene is a stuffed monkey, holding a monkey’s skull:

Also almost artistic, I thought, was the placing of a coin in the eye socket of the skull of this mummy I saw in Bolivia (note also all the coca leaves in the hair!):

Coins were also placed by the skull that welcomes visitors to the fabled Trunyan burial site on Bali, Indonesia:

Further in the back of the Trunyan burial site are skulls stacked together, and partially overgrown with moss:

Another burial site featuring (parts of) skulls I encountered in the Bandia wildlife reserve in Senegal. This is a “griot” shrine (griots = a travelling musician caste preserving oral history):

Skulls, especially in some way deformed ones, also feature a lot in the DT category of medical museums. I have only a few photographic records of these, however, as very often (especially in the West) taking pictures is not allowed in such museums. A notable exception I found was the Medicinsk Museion in Copenhagen, Denmark. Amongst its exhibits was this skull, deformed as a result of leprosy:

And finally, here’s a random set of skulls I spotted in a recess in the outer wall of a church in Lucerne (Luzern), Switzerland:

And that concludes this themed Blog post “DT & Skulls”. I hope you liked it.

2 responses

Grim!

But interesting to read

Thanks – I thought so too.