This is the most fabled of Namibia’s ghost towns, in fact one of the most photographed ghost towns in the world. And indeed it is immensely photogenic. Hence this Blog post will essentially be a photo essay (as promised in the previous Blog post). But first here’s just the briefest of summaries of the history of Kolmanskop:

The town owes its existence to diamonds. In 1908, so during the German South-West-Africa colonial era, a railway worker who had previously had a job at Kimberley Mine, South Africa, discovered a diamond while clearing desert sand off a railway track. He showed the find to his German foreman, soon more diamonds were found and before long a veritable diamond rush ensued. The whole area south of Lüderitz was declared a “Sperrgebiet” (‘forbidden zone’) and to this day this region stretching all the way to the southern border with South Africa can only be entered with an official permit.

At Kolmanskop, or “Kolmannskuppe” in German, originally no more than a lonely stop on the Lüderitz-Keetmanshoop railway line, a small town had established itself by 1912, with a peak population of ca. 350. And it was a wealthy place with all manner of then cutting-edge modern facilities, including an ice factory (for the townsfolk’s fridges, or ‘ice boxes’), a bowling alley and a hospital equipped with state-of-the art machinery, amongst which was the first X-ray machine in southern Africa. But as soon as the easy-to-mine diamond deposits (initially diamonds could simply be picked up from the desert sand by hand) were being depleted and newer, much richer deposits were discovered further south, people left Kolmanskop and flocked there from ca. 1928 onwards. The population of the settlement dwindled and dwindled until sometime between 1956 and 1959 the last residents gave up and moved out, leaving the place a completely abandoned ghost town.

Over the past two decades or so, Kolmanskop has become a veritable tourist attraction. Many visitors coming to Lüderitz do so primarily in order to see Kolmanskop, which is about six miles inland from that coastal outpost. During the regular opening hours (8 a.m. to 1 p.m.) it can get quite crowded here, but I opted for the special “photographer’s permit”, which had to be obtained in Lüderitz the day before and cost three times the regular admission fee. But it was a worthwhile investment as it allowed access to Kolmanskop outside the normal opening times. So I got up really early and arrived at the gate before sunrise. And it was cool to be able to explore and photograph the beauty in decay of this ghost town without ever having to worry about getting other people in the frame, well at least for the first hour and a half or so.

This is the very first photo I took that morning:

This is the part of town that informally was known as “Millionaires’ Row”, as it was here that the diamond mine director and other privileged people had their mansions. The director’s house is actually set back from the rest of the town, seen here by moon- and pre-sunrise light:

I couldn’t enter this house, though, as it was cordoned off because at that time it was being used by a film crew as a set. So I headed in the other direction and before long came to the town’s “Krankenhaus”, i.e. the hospital, pictured below:

Exploring abandoned hospitals I often find additionally eerie, as their silent and lifeless atmosphere so contrasts with what a functioning hospital is usually like (busy, hectic, full of people and activity). And you can come across some abandoned medical machinery too, such as this:

In the rooms to the rear, i.e. facing west, sand is increasingly encroaching on the interiors – including the toilets, such as this one, also still in the hospital:

From the northern wing of the hospital I took this photo through a window – the neighbouring house was the residence of the head “Arzt” (doctor/physician):

From the inside of the doctor’s house I took this photo, looking south towards the hospital on the left and the residential buildings beyond:

By that point the first golden rays of sunlight were streaming in, creating a beautiful atmosphere, as seen in this photo taken by the staircase in one of the larger mansions:

Some of the bathrooms still had bathtubs – though these days they are often filled with desert sand rather than water:

One of the grander buildings on “Millionaires’ Row” is the one marked “Architekt” (‘architect’), seen here in early-morning golden sunlight.

Inside you can still find some stylish wallpaper, only partially damaged by vandalism:

And from the balcony I took the following photo, with the badly damaged house of the “Lehrer” (‘teacher’) next door and the large community hall on the left (more on that below).

Beyond the community centre hall are various workshops, such as the ice factory and the butcher’s. This next photo was taken in the latter and shows vats in which sausages used to be made:

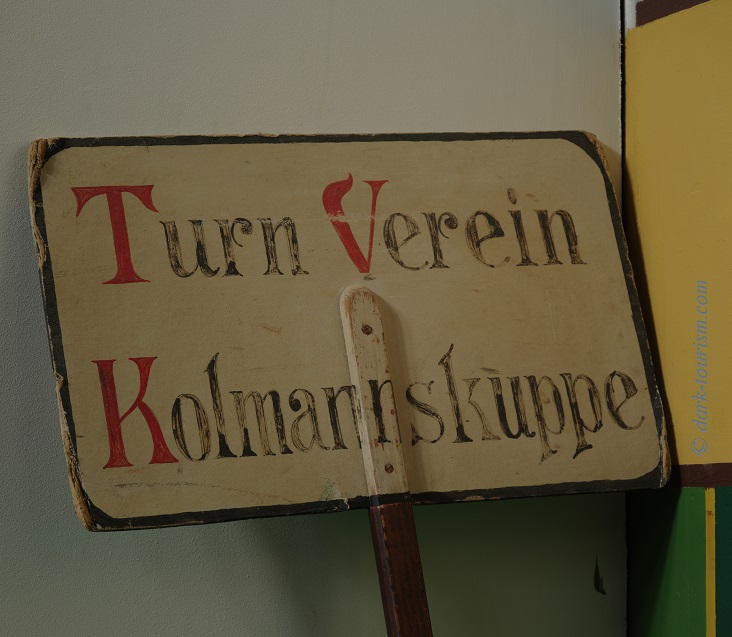

This is also the part of town where the trains to Kolmanskop used to arrive, and an old station sign, giving the German name of the place, is still in situ:

Outside the former shop building, a few narrow-gauge railway carriages are on display, both for passengers and for transporting drinking water into the desert town (the most valuable commodity in such a place without its own water supply):

The shop building is one of the few that have been refurbished. Another is the residential building of the “Ladenbesitzer” (‘shopkeeper’). The interiors have been outfitted with period furniture brought in from elsewhere to roughly emulate the German interior design of Kolmanskop’s early heyday:

.

.

Also in the same building are two restored bedrooms; this is one of them – note the very German-looking garment hanging from the wardrobe:

.

.

In the southern half of the town stand the somewhat more modest residential buildings of Kolmanskop’s former “middle class”. These are clearly less visited by tourists, going by the far fewer footprints left in the sand:

.

.

In the background of this photo you can also see a band of coastal fog that often rolls a few miles inland from the coast, where it is produced by the cold Benguela Current.

It is also in this part of the town where you can find the best and most atmospheric evidence of the shifting desert sand that is slowly taking over the houses (same photo as the one featured at the top of this post):

.

.

Note also the collapsed ceiling in the next room behind the wide-open door. In fact some of the buildings are quite dilapidated and entering is at one’s own risk, as little warning signs inform visitors.

An especially atmospheric photo I find is this next one, where the wall painting seems to continue the desert dunes theme of the floor half filled with actual sand:

.

.

In one of the houses on the furthest edge of the town I even found an indoor sand dune that was still completely untouched:

.

.

And in another I found tracks left by various animals:

.

.

I can’t say what kind of animal would have left the larger prints, possibly some rodent (?), but the finer double-row tracks are the telltale spoors of the tok-tokkie beetle, a species that has adapted to the arid Namib Desert by getting the moisture it needs to survive from the coastal fog that often rolls in from the coast (see above). You can find tok-tokkies performing a kind of headstand in order to capture as much moisture as possible from the morning fog and letting it run straight down into their mouths.

Not all of Kolmanskop is accessible, some seriously dilapidated buildings on the town’s edge as well as the old diamond processing plant and workers’ living quarters are off limits (and fenced off), as seen in this panoramic photo, which also gives an impression of the larger desert setting of the town:

.

.

Also located within the southern part of the town is the former school building (at its peak it had just under 50 pupils), where I took the following photo:

.

.

The very largest building in Kolmanskop is the community centre, which has been painstakingly restored. And its centrepiece is the cavernous theatre and concert hall:

.

.

The various objects seen on the floor here would have been used by Kolmanskop’s “Turnverein”, or ‘gymnastics club’, as a sign in the corner indicates:

.

.

On the lower level of the community centre there’s also a restored “Kegelbahn” (a nine-pin bowling alley) that’s even still in working order, as was demonstrated on the guided tour that visitors can join mid-morning:

.

.

“Kegeln” must have been a very popular leisure activity in German South West Africa at the time. I also spotted a building marked “Kegelbahn” in Lüderitz, and two other ghost towns that I visited in Namibia also featured such bowling alleys, albeit in a far more dilapidated state …

… but I’m getting ahead of myself. Those other ghost towns should be left for another post or two. At 27 images this is already one of the longest photo essays on this Blog. So I shall bring it to a close here. But you can look forward to yet more ghost town images from far less famous and far, far less often visited ghost towns.

2 responses

A great evocative set of photos with lovely descriptions and site history. In a former employment i visited Chile and in particular visited copper and nitrate installations in the Atacama desert, these photos remind me of those visits. In particular Mantos Blancos, Pedro de Valdivia, Maria Elena, Chuquicamata and Calama were some of the places i visited. The layout of the streets in Maria Elena are evocative of the Union Jack.

Thanks! And yes, there is a certain similarity – more so with Pomona and Elizabeth Bay, actually, which are nowhere near as touristy as Kolmanskop. In Chile I visited the former nitrate town of Chacabuco, also because of its history as a politcal prison at the beginning of the Pinochet regime’s brutal rule. That place also has a wonderful middle-of-nowhere feel, and a lovingly restored theatra building …