The idiomatic phrase ‘light at the end of the tunnel’ is probably being used a lot in these weird times– as something that is hoped for, the end of a crisis. Alas, with regard to the current pandemic, that light remains very faint at best, if it’s discernible at all. There’s still no cure, no vaccine, no clear outlook of what’s yet to come. The best we can do is hope that medical science will eventually get us out of this crisis and meanwhile we should behave sensibly … and try not to fall for, let alone help spread, those wild conspiracy theories that are around and apparently are getting as viral as the actual virus – check this (external link)!

With regard to my book, on the other hand, I am seeing the light at the end of that tunnel quite clearly now. I’ll soon have finished the editing of the first proofs, then of course in due course, when all changes, corrections, amendments etc. have been integrated, I’ll get the second proofs to check through again, but the bulk of the work on my part is basically over.

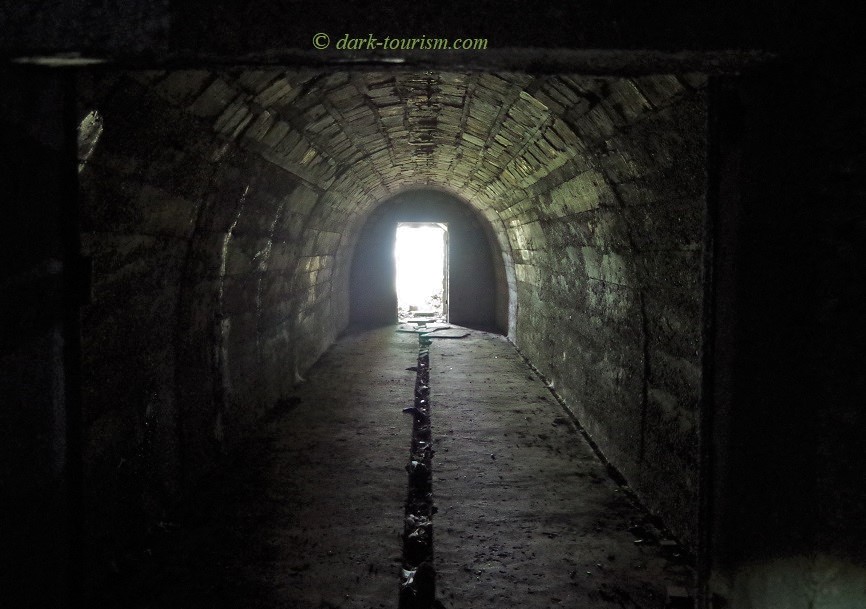

These thoughts inspired me to look through my photo archives searching for images of tunnels with lights at their ends, and indeed there have been some on my extensive travels. Here we go, the first one is this:

This is actually deceptive, in so far as that light far inside the tunnel is a) artificial rather than natural daylight, and b) not yet quite at the end of the tunnel. This is inside Mimoyecques, the spooky underground complex that was to become a multiple “V3” super-gun installation. The V3 was to be the next generation of the Nazis’ ‘wonder weapons’, or ‘retaliation weapons’ (“Vergeltungswaffen” in German – hence the V1, V2, V3 designations). The Nazis hoped, somehow, that these would turn the tables towards the end of WWII, at a time when that war was in actual fact basically already lost for Germany. So what these new technologies really were was pure terror weapons, of next to no military value, just there to indiscriminately destroy and kill civilians. Thankfully, this system at Mimoyecques, which was intended to shower London with projectiles at a rate of 600 per hour, never got beyond a prototype, which didn’t even work, and the underground site in the Pas-de-Calais region of France was put out of action by the Allies by means of deep-penetration ‘Tallboy’ bombs even before the tunnels could be completed.

Next up is this tunnel:

This time the light at the end of the tunnel is real, i.e. it is daylight, but the nature of the tunnel is vaguely related to the previous one. This is at Ebensee in Austria and it’s also a Nazi tunnel. Here, an underground arms production facility was to be installed inside a mountain where it would be safe from Allied bombing. It was intended for the manufacture of engines and parts for tanks and fighter planes as well as the assembly of V2 missiles. But, again, there wasn’t time for it to be completed and become operational before the end of WWII. So the tunnels remain unfinished.

As was usually the case with such Nazi projects, it was constructed by making use of forced labourers from an adjacent concentration camp. The worst site of that nature was Mittelbau-Dora, where V1s and V2s were indeed mass-produced by forced labourers under atrocious conditions so that the camp became one of the deadliest within Germany. Ebensee could have been similar, but only one main tunnel was finished (the one you see in the photo above), the side tunnels were in their early stages of drilling when the project stopped with the surrender of the Third Reich. After the war, the remnants of the adjacent concentration camp were cleared away to make space for a new settlement. Only a cemetery with a modest memorial commemorated the dark history of the place. The tunnel was later made accessible for the public and a small exhibition about its history was added. In German the site is referred to as a “Gedenkstollen”, roughly ‘commemoration tunnel’.

With the next place we switch sides, as it were:

This is the main connecting tunnel underneath Valetta, Malta, with the Lascaris War Rooms deep inside the rock. It was the Allied HQ from where, amongst other things, the Allied landing operation in Sicily, Italy, was planned and orchestrated, which was a decisive step in the WWII operations in the Mediterranean and would soon after topple Mussolini. The light just about visible at the far end of this tunnel is at the western end of the Lascaris Tunnel. The war rooms have been faithfully restored and are now a major visitor attraction in Malta and a must-see for any war history buff.

But back to the Nazis one more time:

This image may be familiar to those who’ve been following this blog for a while, namely from a post on 21 July. This is inside a bunker (so not strictly speaking a tunnel, but close enough) of the Wolfsschanze complex in north-eastern Poland, which is where Hitler had his main HQ during most of WWII. Here the upper echelons of the Nazis hid in gigantic reinforced concrete bunkers as they directed the war, especially on the Eastern Front. As fortunes turned against the Nazis (esp. after their defeat at Stalingrad) and eventually the Red Army drew close in their push westwards, the Wolfsschanze Nazis upped sticks and fled. They tried to blow the bunkers up before they left, but with only limited success. Now they provide an eerie memorial site: huge hulks of overgrown blocks of concrete, some broken and semi-toppled, others still standing. There’s also a plaque commemorating Stauffenberg’s assassination attempt on Hitler on 20 July 1944 that took place here. But still, some of the clientele you can encounter here seems a bit dodgy. I’ve even spotted swastika graffiti. That’s always the problem with such difficult sites: how to keep the balance between commemoration and making authentic places accessible and at the same time preventing the sites from becoming pilgrimage destinations for neo-Nazis nostalgic for the olden days of Hitler & Co. The curators of the documentation centre at Obersalzberg, Hilter’s retreat resort in Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, face a similar task.

But back to tunnels. The next one is associated with one of the Nazis’ allies, who, we’ve already mentioned:

This was taken at Villa Torlonia, which used to be Italy’s fascist leader Mussolini’s home in Rome. Here he had a wine cellar converted into a first air-raid shelter as he was getting increasingly paranoid about the possibility of becoming the target of Allied air strikes. As Mussolini considered this first shelter to be insufficient, he later had a proper reinforced-concrete bunker constructed … but never had chance to use it as he was deposed before the bunker was finished. This underground site has only recently been rediscovered and made accessible to visitors on guided tours.

And here comes another tunnel associated with yet another Nazi ally:

This light at the end of a tunnel is at the end of an underground escape tunnel that Croatia’s Ustashe Nazi leader Ante Pavelić had had constructed under his Zagreb home of Villa Rebar. Of the house of that name next to nothing remains today, beyond the foundations and remnants of a garage, but the underground tunnels are still there and form an attraction for urban explorers. Only tours of that nature ever take foreign visitors to the site – it is otherwise totally non-commodified for tourism.

Next tunnel, staying in Croatia – this might also be familiar to long-term followers of this blog:

This is the end of one of the four tunnels that provided access to the underground airbase of Željava, which was constructed during the Cold War for the Yugoslav Air Force to station squadrons of MiG-21 fighter jets safely protected inside a mountain. But in the wars that accompanied the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, this site was given up and largely destroyed, but the huge tunnels remain, burnt out and now strewn with debris. Inside it’s pitch-black dark once you get in more than a few dozen yards. It’s probably the No. 1 attraction for urban explorers in the Balkans today. Powerful torches are essential! See this earlier blog post about this extraordinary site.

Next up is another Cold-War-era relic, this time in Germany:

This is at the former West German ‘government relocation facility’ Marienthal near Ahrweiler, south of Bonn. This was constructed in the 1960s/70s for the FRG’s government to take shelter in in the event of (nuclear) war. It was constructed inside former train tunnels which were vastly expanded to become an underground town and command centre with space for thousands of officials and their support staff. By the time it was ready for use, though, it was as good as redundant, because by that time intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) had become the main nuclear threat and the bunker would a) not have withstood a direct hit by a thermonuclear weapon, and b) it was too far from the then capital Bonn for all those hundreds of government members and their personnel to make it here in time before the missiles hit (the forewarning time was reduced by ICBMs to no more than half an hour).

After the end of the Cold War, the Marienthal site was decommissioned and largely gutted – except for a short stretch that now serves as a unique Cold War museum of sorts (visitable on guided tours only). This view was at the end of the preserved part, looking into a gutted tunnel section.

I admit that strictly speaking there is absolutely no light at the end of this tunnel – however, there is a little light coming from an opening on the side of the tunnel. What may be behind that opening, I have no way of telling. It’s a little intriguing bit of mystery.

And finally I take you back to the beginning (and to the lead photo at the top of this post), namely back to Mimoyecques in France. And I can make up for the lack of genuine natural light seen at the ends of some of the previous tunnels. In this photo you can see daylight flooding in in abundance as we emerge from inside the tunnels back into the world outside …