There has been extremely worrying news the last few days from a little-visited region in the Caucasus that was included in my trip there ten years ago – Nagorno-Karabakh. Apparently the ‘frozen conflict’ over this contested region has flared up again and escalated into military confrontation and fighting, with already over a hundred dead, so it’s worse than the last time around in 2016. Moreover, now Azerbaijan is receiving open backing by Turkey, while Armenia is banking on support from Russia. So this has the potential to spiral into a full-on proxy war (as nearly happened in Syria a few years ago).

A little bit of background: Nagorno-Karabakh was a semi-autonomous region (‘oblast’) within the Azerbaijani SSR during the Soviet era, even though most inhabitants were of Armenian descent. Allegedly the region was integrated into the Azerbaijani SSR by Stalin himself redrawing the borders of the young USSR. As long as the Soviet Union lasted this wasn’t quite such an issue, although there were already calls for separation from Azerbaijan in the late 1980s. After the dissolution of the USSR, Nagorno-Karabakh found itself part of the newly independent state of Azerbaijan, a predominantly Muslim country with a Turkic population. The Armenians, non-Turkic Christians, weren’t accepting this and took to arms. In the early stages of the conflict, the Azeris had the advantage, but later, with military aid from Russia, the tables were turned. After a few tens of thousands had lost their lives in the conflict, a ceasefire was brokered, but the situation has remained unstable ever since. The bizarre situation is that under international law the region remains de jure part of Azerbaijan, but de facto it is controlled by Armenia. The region’s inhabitants are ethnic Armenians, while the Azeri minority who used to live within Nagorno-Karabakh fled eastwards, becoming internally displaced persons within Azerbaijan.

Nagorno-Karabakh declared itself an independent state, and now calls itself Artsakh, but is recognized only by a couple of other ‘breakaway republics’ that are also mostly unrecognized by the international community. But on the ground the situation stabilized to a degree, the odd skirmish in the ‘buffer zone’ notwithstanding.

What will happen this time is anybody’s guess. But the news of the renewed outbreak of the conflict brought back memories of my trip there in the summer of 2010, at a time when things were much calmer though it was always potentially volatile. So in this post I give you a little photo essay drawn from my archives.

The photo at the top, repeated below, may in fact be familiar to those who’ve followed this blog from its beginnings, as it featured in a post on the theme “the fluffy side of …”. I like to refer to it as a “tapestry of war”. It’s an exhibit in the Museum of Fallen Soldiers in Artsakh’s ‘capital’ Stepanakert.

The figures behind the tank in the bottom right corner are a depiction of what could be called the “national monument” of Artsakh, officially named We are our Mountains, but better known informally as Tatik Papik, meaning “grandma and grandpa”. Here’s a photo of the monument depicting a veiled woman and a bearded man:

In Stepanakert I spotted some flagpoles that in addition to the “national” Artsakh flag and the Armenian flag (which are identical except for the line of white steps that runs through the right half of Artsakh’s flag) also had a tattered Russian flag and a stars-and-stripes flag (due to the large Armenian diaspora in the USA there’s a connection).

And here’s a photo of an ‘official’ building in Stepanakert (I think it was the Ministry of Foreign Affairs where I had to collect my Artsakh visa) with walls clearly showing signs of war damage, only half-heartedly touched up:

In the town centre I saw a fence around a construction site that featured large photos from Artsakh heritage sights alongside martial images of military parades:

The fence even featured a photo of a wartime tank wreck:

Another exhibit in the Museum of Fallen Soldiers was this diorama of the region, with little lamps highlighting battle hotspots from the war in the 1990s:

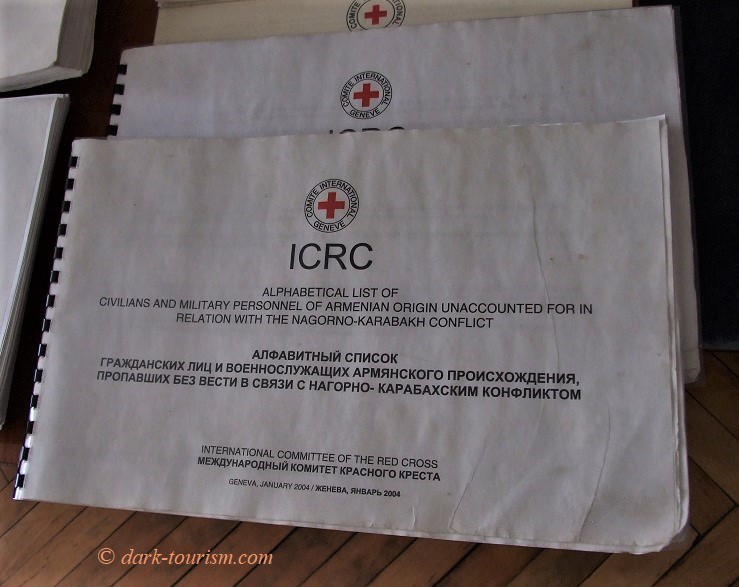

In the neighbouring Museum of Missing Soldiers, amongst plenty of more symbolic and glorifying artefacts, there were also these copies of a Red Cross report about people from the Armenian side who were still “missing” after the ceasefire.

When touring the region a definite top sight is this monastery church – and frankly, how much more Armenian could it get?

In the grounds of the monastery are also typically Armenian religious stones called “khachkar”:

Behind the monastery there is also a cemetery where some of the tombstones are clearly for fallen fighters from the 1990s conflict here:

Before you get the wrong impression that I’m one-sidedly standing with the Armenians in this issue: I am not. I’m also aware of Armenian wrongdoing. For instance, contrast that Armenian cemetery with this damaged former Muslim cemetery:

This is clearly a victim of the Armenian advance into Azeri territory towards the end of the conflict in 1994, when the Armenians declared a ‘buffer zone’ of occupied Azeri territory around Artsakh (this includes not only the corridor between Armenia proper and Nagorno-Karbakh to its west, but also a strip of land to the east of it). The scorched-earth cemetery is on the outskirts of what was the Azeri city of Ağdam, now the world’s largest ghost town – although it is effectively just a sea of ruins since the Armenians have stripped the buildings bare of anything that could be useful. Here’s one of those ruins:

Ağdam is not the only ghost town here, though, you can see lots of abandoned settlements in the buffer zone, alongside wrecks of vehicles, such as these shells of buses:

Also by the roadside I spotted the odd surviving Soviet monument, like this one:

Nagorno-Karabakh’s second-largest town is Shushi (or Suşa in Azeri), which used to be a mostly Azeri pocket within the otherwise predominately Armenian region, and hence became a semi-ghost town. Back in 2010, I could still spot plenty of ruined shells of apartment blocks such as this one:

The capture of Shushi was a decisive moment in the war for the Armenian side and is hence celebrated in the war-themed museums as well as by this roadside tank monument on the approach road to this hilltop town.

As is tradition all over the former USSR, this kind of tank monument is a must-do stop and photo shoot backdrop for wedding parties. And so it happened when we were there. Really quite a bizarre scene. I waited until the party had moved on (presumably to the next monument) before I took this pic.

In fact the three days I had in Nagorno-Karabakh weren’t all just gloom and doom and war remnants. In Stepanakert I also spotted this cute mural:

What I never saw, though, were any other foreign visitors. Consequently we were eyed with curiosity by the locals, but not in a threatening way. Stepanakert, incidentally, was still very Soviet in atmosphere and the dominant language spoken was not Armenian but Russian.

In terms of food and drink, offers in town were a bit limited, but we did find an open-air cafe that served local wine and a rather Eastern take on pizza. This was called “Pizza Gorgonzola”, but probably only so that it sounded somewhat Italian, as it did not have any actual Gorgonzola cheese amongst its toppings – but it featured tinned peas!

But so much for reminiscing about my Caucasus trip back in the summer of 2010. You obviously wouldn’t want to go there right now. But I sincerely hope that full-on war can somehow be averted and a return to diplomatic modalities can be achieved. However, how to bring about any real and lasting resolution of the underlying conflict, I cannot see, to be honest. The situation is at least as vexed as the Palestinian question is in the Middle East. I just hope that Turkey doesn’t now push for a proper war, which would then most likely draw Russia in as well, and that could be really dangerous for the entire Caucasus region. So fingers crossed it won’t come to that (though I’m struggling to be overly optimistic right now …).