It’s been a long while since the latest Blog Post, and a new one is more than overdue. So here we go.

I’ve finally finished processing the many photos I took in August in Namibia. Most were taken in RAW format so required a lot of developing/processing (white balance, exposure, etc.) so that was quite a bit of work, but that’s now done. In this new post I’ll give a general overview and a few taster photos (15 in total) – naturally with an emphasis on dark-tourism-relevant aspects.

The main type of dark destination that Namibia excels at are ghost towns, the most famous being Kolmanskop. But I also visited a few additional ones that are far less well known and where access is much more restricted. I’ll give all these places their own separate Blog Posts (and stand-alone chapters on my main website), as well as a couple of extra ones about other places, over the course of the next few weeks and months.

In the text below there will be a number of references to Namibia’s unique history. I suggest you take a look at this short summary text before reading on if you’re not yet so clued up about Namibian history (and I wouldn’t be surprised or hold it against you – I knew precious little myself until I started reading up on these things as I prepared for travelling to the country).

One of the very darkest chapters in Namibian history was what is widely regarded as the 20th century’s first genocide, namely against the Herero and Nama peoples at the hands of the German colonial military, the so-called “Schutztruppe” (‘protection force’). This took place (mostly) between 1904 and 1907. One particular place of infamy was Shark Island – a rocky outcrop to the north of the town of Lüderitz on southern Namibia’s barren desert coast. Here, the Germans set up a concentration camp. “Living” and working conditions were atrocious and about half the inmates did not survive. The bodies of the dead were often simply thrown into the ocean where they would become food for sharks – hence the name of the place allegedly came about (so the park warden told us at the gate). A number of skulls of the dead were severed and sent back to Germany – for “research” … into the then en vogue discipline of “eugenics” (which paved the way for the later racist policies of the Nazis too). Today Shark Island is linked to the mainland, thus having become a peninsula. This it what it looks like now:

.

.

Nothing remains of the concentration camp – and ironically most of the land is now in use as a camping site. There’s only a small cluster of memorial monuments and plaques – an uncomfortable juxtaposition of ones commemorating the victims next to German ones commemorating the “Schutztruppe”.

Lüderitz has many architectural relics of the German colonial period and every so often you come across German names and signs, such as in this next photo:

.

.

“Lesehalle” means ‘reading hall’, so that was probably a library, and “Turnhalle” means ‘gymnasium’ – so both body and mind were looked after in this so very German town …

In Swakopmund, which is Namibia’s second-largest city – and its most touristy – you can also find plenty of architectural relics from the German period. And there’s also another controversial monument erected in honour of the fallen soldiers of the “Schutztruppe”. Here’s a photo:

.

.

A German-era relic of a very different sort – and in the middle of nowhere – is Duwisib Castle. This most unexpected folly was the dream home of a German ex-Schutztruppe officer and his American wife. It was completed in 1909, and the couple had only a few years to live in it before WW1 ended it all. Unfortunately I was only able to see this strange pseudo-Gothic edifice from the outside. The interior, said to be even more outlandishly OTT, was sadly not accessible at the time I was there.

.

.

While the Germans were the first ones to get a proper colonial foothold in Namibia (followed by decades under South African rule until independence in 1990), the very first colonial power to drop by was Portugal, when a certain captain Diego Cao made a brief landing at a peninsula on the Skeleton Coast in 1485 and erected a cross. Hence the place became known as Cape Cross. The Portuguese didn’t linger, though, having seen that this stretch of coast was pure desert with no drinking water anywhere near and next to no vegetation. So they lifted anchor and sailed on. The original cross was dismantled by the Germans centuries later and taken to Germany. But there’s a replacement replica today:

.

.

Cape Cross is also home to a very large fur-seal colony, as you can see in the background behind the cross. In fact up to 100,000 individuals come together here to breed. It’s anything but a peaceful place. It’s noisy and the stench of the amassed seal excrement is quite overpowering, much worse than what I had encountered at penguin colonies in the Falklands …

The Skeleton Coast is so called because of the many wrecks of ships that found an unfortunate final resting place on this forbidding desert coast. These days only a few older shipwrecks remain, as they are slowly eaten away by the elements, especially the waves of the salty ocean. So often all that’s left are some rusty engine hulks. In recent decades hardly any new wrecks have appeared on this coast – thanks to modern GPS-based navigation aids. One exception, however, is this fairly new wreck:

.

.

This is the “Zeila”, which became stranded here in 2008. The fishing vessel had actually been towed towards India where it was supposed to get scrapped, but apparently the towing line came off and the boat ended up here instead. Nobody got hurt in the incident, but it’s a sobering sight to see such a relatively new and intact wreck being battered by the waves here.

Many of the older shipwrecks are very difficult to access. Amongst the most fabled ones is the 100m long “Eduard Bohlen”, which beached here in 1909. In the meantime the desert dunes have moved on, so that the wreck now lies over 300m inland – and has formed its very own dune:

.

.

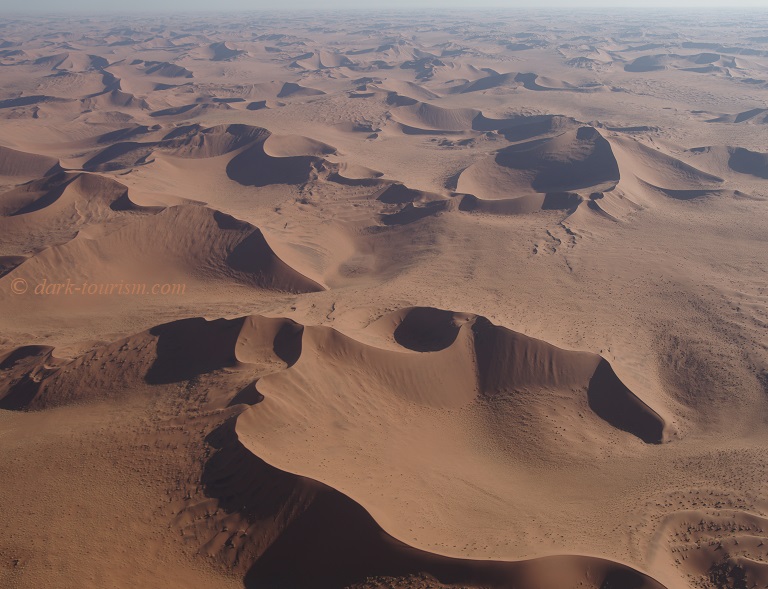

This is in a very remote location, only accessible overland by guided tour with a sturdy 4×4 and skilled driver and it’s a very long all-day excursion. I saw the wreck from the air, as part of a two-and-a-half-hour scenic flight in a small plane that took off from Swakopmund, flew inland over some spectacular desert scenery (see below) and finally up the coastline passing some abandoned settlements, mines and a couple of shipwrecks, including this one, which the plane circled three times at relatively low altitude so everybody could get decent photos.

Apart from shipwrecks you also encounter quite a few car and truck wrecks, such as this pair at Solitaire:

.

.

Solitaire is indeed a place of solitude – basically just a fuel station with a shop and a famed bakery, surrounded by vast empty land. These days there is also lodge accommodation at Solitaire, but most people just drop by to refuel and maybe shop for provisions before pushing on, as Solitaire is en route to Sesriem. That’s the name of a place that serves as the gateway to Sossusvlei, the jewel of the Namib-Naukluft National Park. It’s here that you find those famous red dunes, including allegedly the world’s highest at ca. 350m (that’s higher than the Eiffel Tower!), sheer mountains of sand! I first saw them from the air on that scenic flight already mentioned. That’s when I took this aerial shot of a part of the desert that is totally desolate and never visited by anyone (same photo as the featured one at the top of this post):

.

.

There’s always something slightly disconcerting about flying over territory so in the uninhabited – and uninhabitable – middle of nowhere. You really don’t want to go down in a plane crash there …

A central stretch of this desert, however, is quite easily accessible by road and has become one of the main tourism draws of Namibia: Sossusvlei. This is the course of a mostly underground river – hence you can find some shrubs and trees here. At the end of Sossusvlei I even spotted a small lake from the air. The main attraction, apart from the towering red-sand dunes, is a place called Dead Vlei. This takes its name from a grove of dead acacia trees, some several hundred years old, that all died when the underground river changed its course thus cutting the water supply. Now the dead trees standing like sculptures in the bone-dry clay pan make for fantastic photography opportunities:

.

.

The Namibian deserts aren’t all dead, though. In fact, the Namib is one of the planet’s oldest deserts, and hence some life forms have had the time to evolve into some extreme ecological niches. One fabled example is a type of beetle called tok-tokkie. These get their water from standing on their front legs with their rear raised up in the air catching the frequent morning mist drifting in from the coast, thus collecting a minimum amount of moisture to survive on.

I went on a “Living Desert” tour, which was immensely educational. We were introduced to a number of desert-dwelling species referred to as the “Little Five” (in allusion to the “Big Five” of African safaris), creatures that somehow manage to survive in this extreme landscape. Amongst these was also a sidewinder snake, seen in the following photo:

.

.

Normally these snakes hide just under the sand surface with only their eyes poking out, almost invisibly. But when disturbed (or hunting) they move across the dunes in a sideways fashion leaving characteristic S-curved trails. These snakes are actually quite poisonous and our guide reported that a colleague once got badly bitten. The bite is not necessarily deadly, but excruciatingly painful, and it can have long-term after-effects such as blurred vision. So utmost care has to be taken to avoid getting bitten.

On this trip I concentrated mostly on things that are uniquely or at least typically Namibian, so I gave the not so arid north a miss and did not go on any conventional safaris. I had done that before in South Africa, Zimbabwe and other African countries, so I thought I’m not really missing out.

However, there were some wildlife encounters, though not in the real wild but in sanctuaries set up for animals that were either orphaned or had become problematic in terms of wildlife-human encounters and are now too habituated to be released back into the wild. This included a bunch of cheetahs at a wildlife sanctuary farm in the inland Kalahari bush, where I was able to witness a cheetah feeding. Here’s an image of one of the cheetahs having just been fed a big bowl of raw meat … you can see blood still dripping from his mouth:

.

.

At another wildlife sanctuary they had yet more carnivores whose feeding one can witness on a special tour. This sanctuary also included a pack of African wild dogs relocated from the north of the country (so they were out of their natural habitat). Here’s one munching somewhat gruesomely on one of the dead chickens they were thrown:

.

.

By the way, I really don’t know why that is, but so many people when they see an African wild dog (aka “painted dog”, because of their individual patterns) cry “oh, hyenas!” … why? The two species barely look alike (hyenas are much, much stockier and more muscular, have lower hind legs, and regularly spotted fur – check out this older animal-themed blog post featuring hyenas to see the difference!).

One extremely rarely seen predator cat to behold on this tour was a pair of caracals. They are so elusive that you never see these on safaris. They are normally semi-nocturnal and live as loners. Here they had two individuals – who nervously eyed and hissed at each other, as seen in this photo:

.

.

Seeing one of these beautiful felines was definitely a highlight of the whole trip … though admittedly we’re now going beyond the outer fringes of what constitutes dark tourism. But I didn’t want you to miss out on this nice photo 😉

Finally, one very special dark-tourism activity I had hoped to go on during this trip did not happen: the tour of Rössing uranium mine. This is one of the largest open-cast uranium mines in the world – and until recently one of the very few that allowed visitors in. Anything to do with the nuclear industry is normally highly secretive and away from the public eye. Unfortunately these tours, which used to be organized from the Swakopmund Museum, were suspended with the onset of the Corona pandemic in March 2020. Then the mine was taken over by a Chinese company. And, as I already feared, the new Chinese owners do not like anybody from the public seeing anything here and so never resumed those tours. Shame.

However, as a slight consolation, I visited an abandoned former tin mine near the provincial town of Uis. And that big, brutal hole in the ground was also quite something to behold (not with the dark association that comes with uranium, but this was the best I could get):

.

.

And that’s it for now. Following this rather kaleidoscopic post about Namibia generally, the next few posts will be more targeted on specific dark-tourism attractions in that country … if there aren’t any independent current-affairs posts in the meantime.

By the way: I actually enjoyed being away and largely cut off from current affairs in the wide, empty and wonderfully silent expanses of Namibian desert. There was often no Internet or mobile reception. But not hearing constantly about war and other woes in Europe and beyond, was, to be honest, quite relaxing. Also, the dark-tourism proportion on this trip was relatively lower than on most of my previous travels over the past 15 years, and it was organized in such a way as to go at a slower pace than I normally do. And that too had a pleasant effect. I really felt I was able to recharge my batteries on this trip.

But now it’s back to city life and noise – and back to writing up for dark-tourism.com and this blog … and at some point there will be further travel planning (so far no ideas are concrete enough to be brought up here yet).