Nauru is the world’s smallest independent island nation (and the third smallest of all sovereign nations). It’s located in an isolated spot close to the equator in the south-west Pacific far from any other islands. I first heard about Nauru as a teenager in school and was fascinated by its extreme rags-to-riches-and-back story. Back then in the late 1970s Nauru was still one of the richest nations on Earth, thanks to the mining of high-grade phosphate deposits on its central plateau (a substance derived from guano – bird poo to you and me – which makes for a much sought-after fertilizer). But even back then it was clear that the deposits would be depleted before too long. Indeed from the late 1980s/early 1990s mining declined to a mere fraction of its former output, though a small-scale operation is still ongoing.

With the main source of income disappearing Nauru tried all manner of investment projects, e.g. in Australian property and construction, but most of them failed. For a while Nauru invited alleged “banks” to have (virtual) branches on the island – basically for money laundering, which brought some revenue in but resulted in even more international criticism. Despite all the desperate (and mostly botched) efforts to boost the economy, unemployment skyrocketed and the average per capita GDP shrank to a fraction of what it used to be. Now Nauru is about the poorest nation in the Pacific.

From the early 2000s, another form of income generation arrived, namely in the form of the so-called “Pacific Solution” to Australia’s refugee problem. Under that scheme the asylum seekers were “outsourced” to specially established refugee detention centres on the mining-depleted wastelands of inland Nauru (referred to locally as “Topside”). In return Australian aid for Nauru was coming in. The refugee detention camps, euphemistically dubbed “Regional Processing Centres” (RPCs), operated for a few years, attracting much international criticism from human rights organizations in the process, then the scheme was stopped, only to be restarted again a few years later. At the time I started planning my trip to Nauru, the RPCs were closed, but in the meantime they reopened, with just over a hundred refugees on Nauru at the time I travelled there.

Finally making it to Nauru in August 2024 is one of the jewels in my travel history crown, I think, even though the destination in itself is hardly of great attraction. It’s the least visited country on the planet – and there are many reasons for that, beginning with the bureaucracy involved in getting a visa, incredibly expensive flight fares (and somewhat erratic schedules) on the national airline, complicated logistics to arrange accommodation and on-the-ground transport, and then really not all that much to see once you’re there. But for me it had been a lingering dream since my schooldays to one day travel there. I’m glad it worked out as an add-on to my longer Australia trip (for that see this recent Blog post). And of course I had good professional reasons for going there …

And here dark tourism comes in to play. Nauru is anything but your typical cliched Pacific coral island paradise, and instead it has dark history in spades. From early encounters with European explorers, traders, whalers and convicts, to colonization by Germany and subsequently Australia, foreign exploitation of its riches (all that phosphate), then occupation by Imperial Japan during WWII, which left many relics, then again under Australian control until independence in the late 1960s and subsequent over-exploitation of the phosphate deposits making the island so rich for as long as it lasted, and then most recently those RPC detention centres.

In what follows I’ll give you just a photographic overview of what there is to see on Nauru, so it’s basically another photo essay. For more information refer to the Nauru chapter on my main website.

First off, here’s a photo of the little island’s tiny airport with one of the national airline’s 737 jets parked on the apron:

The story of the airline fits in with Nauru’s contemporary history. Even insisting on having a national airline for a people numbering under 12,000 seems a bit preposterous, especially at a time of economic decline. And indeed the airline contributed to that decline, flying mostly with the majority of seats empty and thus remaining deep in the red, until “Air Nauru” was shut down. It was resurrected under the new name “Our Airline” (a weird marketing attempt that yielded no positive results). But since 2014 it’s been operating under its current name “Nauru Airlines”. Now completely state owned and benefiting from heavy subsidies from Australia, the airline has grown into a small fleet of 737s, which Australia reserves the right to requisition as needed, e.g. when another contingent of refugees are to be transported there. Its actual commercial operation is mainly between Nauru and Brisbane in Queensland, Australia, plus a few destinations on other remote islands in the Pacific. In fact, on my flight out to Nauru most other passengers were using Nauru merely as a hub for onward flights … including a sizeable group of men all wearing T-shirts showing the famous Baker shot mushroom cloud on their final destination: Bikini.

The next photo shows a sign-pole outside the Capelle & Partner supermarket at Ewa Lodge (where I stayed for two and a half nights):

As you can see the distances marked on these signs are considerable, even the Pacific ones, while Israel is halfway around the globe and Taiwan still 3500 miles away. Incidentally, Nauru’s relationship with Taiwan is also, well, interesting. Nauru switched allegiances to either the PRC or Taiwan repeatedly, each time benefiting from subsidies/investment paid by the respective countries (and yes, Taiwan IS a “country” to all intents and purposes, no matter what nonsense the Xi Jinping regime may claim). With the latest move in early 2024, Nauru severed ties with Taiwan one more time, and fell in line with the PRC again, recognizing that country as the sole China. I wonder whether they will switch back again at some point.

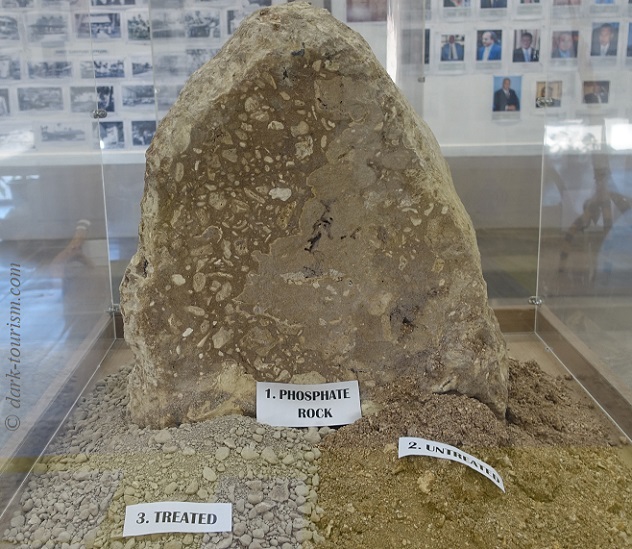

The first stop on the tour of Nauru I was on was the island’s small museum. Inside is an endearingly amateurish exhibition with plenty of photos, historic and contemporary, as well as artefacts, many of which are related to WWII (wreck pieces of Japanese and US war planes, say). Of course the phosphate mining industry is also a major topic. The photo below shows an exhibit of phosphate rock and the derived material:

After a look around the government quarter next to the museum another stop was at the island’s WWII Memorial:

Behind the memorial you can make out parts of the phosphate cantilevers. Here’s a photo of them without obstruction:

These are still used for loading processed phosphate on to cargo ships, just no longer all that often (I never saw any such ships during the time I was there). These cantilevers are indeed perhaps the most iconic sight of Nauru. They even feature on postcards and souvenirs! (It says something about how attractive an island it is overall – but I for one find such industrial structures genuinely fascinating!)

There’s a second, older set of cantilevers, these partially collapsed into the coral reef that rings the entire island (same photo as the featured one at the top of this post):

It is not quite clear why these cantilevers collapsed. My guide said they were casualties of bombing during WWII – and since Nauru was indeed the target of German, Japanese, Australian and US shelling/bombing that could well be so.

The next day we explored the Topside and Nauru’s colonial and war relics. The first stop was a site that was once a communications post during the German colonial period, later allegedly used as a prison, both by Germany and later Japan:

The place is not commodified in any way, you just clamber about trying to ignore the many graffiti. At one point you come to a kind of bunker with a steel door and tiny shuttered windows:

This may have been a prison cell. There are also claims there’s a former gas chamber here, used by the Germans to execute islanders who refused to work for them. But I’ve not found any halfway reliable evidence for this, so it remains an anecdotal and perhaps somewhat dubious story.

Behind another steel door a tree was growing inside the cell (if it was one). I always find such images especially atmospheric (see also Île St-Joseph):

After this we climbed to the top of what’s called “Command Ridge”, the highest point on Nauru (at ca. 70m above sea level). Here various relics from the military occupation of Nauru by Japan during WWII can be found. The “star piece” amongst these is this massive dual anti-aircraft gun:

Driving around Topside you can see how ravaged the once fertile land on the plateau became due to the phosphate mining:

Immediately after the phosphate mining had devoured these lands it would have been a totally lifeless moonscape. Now that mining is over in most places, some vegetation is beginning to return. But the soil is so depleted that nothing of agricultural use could grow here again.

That’s also for sheer physical reasons. The ex-coral pinnacles from which the phosphate rock has been stripped away can stand over 10m (30 feet) high in places, and are often densely packed together. You could hardly get through these forests of rocks.

Exploring Topside we also stopped by the current small-scale phosphate plant, seen in the next photo:

Rumbling about in this bizarre netherworld are huge mining trucks transporting the phosphate rock to the plant, all the while kicking up clouds of polluted dust.

Also on Topside we passed a couple of those controversial asylum-seeker detention camps. The one in active use at the time, RPC 1, was guarded and taking photos was strictly forbidden. But when we passed one of the camps currently only “on hold” but not in active use, I was able to snap this photo of the gate:

We also passed a former high-security refugee detention centre, which has meanwhile been turned into Nauru’s National Prison:

Outside guided touring I also had a hire car to drive around the small island myself … It’s so small, in fact, that it is impossible to get lost, and no maps are needed. There’s only the one tarmacked ring road going round the coastline fringe and that’s only about 12 miles (19 km) long, so doesn’t take long to drive.

Driving around Topside, mostly on dirt tracks, is slower still and very bleak indeed. Apart from the phosphate mining remnants and the moonscape it left behind, and of course those detention centres, there’s precious little of note to see here from a car. One exception is what I would call a “car cemetery”: dozens and dozens (possibly hundreds) of old cars simply dumped next to the roadside, often piled three or four high. Here’s one photo:

You can find lots of car wrecks elsewhere on the island too, just not as amassed as here. I presume it’s just too expensive and too much effort trying to get old, no longer used cars off the island, hence they’re simply dumped and left to rust away.

Speaking of cars: there goes a story from Nauru’s rich days that one official imported an Italian sports car (the luxury name beginning with “L”), only to find out when it arrived that he couldn’t fit behind the steering wheel … Nauruans are notoriously the most obese people in the world by far (due to the mostly over-processed imported junk food Nauruans eat, also resulting in the world’s highest diabetes rate).

The one food Nauru has plenty of itself, other than coconuts that grow on the coastal fringe, is tuna from its wide expanse of otherwise rather untouched ocean. I saw fresh tuna advertised at many a private house and it also featured heavily on the menu of the island’s only proper restaurant. The small fishing harbour at Anibare Bay has a structure marked “Nauru Fish Market”, but I never saw any action there:

The memorial cross, by the way, is dedicated to all those who lost their lives as a result of rip tides at the previous boat channel that was once located here.

Not far from the boat harbour and fish market is what is/was the island’s largest Hotel, called Menen (like the district it is located in), totally oversized at 119 rooms for a nation that receives as few as 200 visitors a year. I had read about its already near-defunct status years ago (in Tony Wheeler’s “Dark Lands”). When I visited the place it was practically deserted altogether. The lobby, reception, bar and other public areas were all empty and dark, the swimming pool still waterless, and whole blocks seemingly crumbling away:

However, there were a couple of cars parked outside and on a few of the hotel room balconies I spotted washing drying. So maybe it is used for contract-worker accommodation on a smaller scale (or maybe for people involved in the running of the refugee camps).

Another spooky place we visited on our last day was a cave that was allegedly once used by the Japanese occupiers as a hospital.

Inside next to nothing was left, and apparently the limestone is still growing so that the cave gets smaller and smaller over the decades. The walls inside feature plenty of graffiti, mostly boring and uninspired, but this one was quite fitting for the gloomy atmosphere in here:

The last day I had on Nauru was a Sunday – and as the island is a deeply old-school Christian country, life more or less stands still on a Sunday. All shops are closed, except for a few ones run by Chinese, and the only places that are operational are the churches (and, thankfully, the airport for my flight home later that afternoon). It had the advantage that the old phosphate plant in Aiwo district, which we had driven past a few times before, was totally deserted on a Sunday. So I grabbed the opportunity for a bit of urbexing in the tropics, as there were no guards to stop me:

Earlier we had already explored a huge former phosphate storage hall next to the plant – with a heap of old phosphate now growing a green veneer of moss:

Finally, on the western side of the island there are two quite prominent Japanese-era pillbox bunkers directly by the roadside on the beachfront behind the coral reef ring.

Those were the highlights of my short trip to Nauru in August 2024. It was interesting (and very different from anywhere I’d been before) and also the fulfilment of a near lifetime dream to visit this forlorn place. But I honestly do not think it’s a place I’d ever visit again. The extremely humid tropical climate was taxing and there’s next to nothing to keep you entertained once you’ve seen the few sights (many of which in other countries would not remotely qualify as tourist sights to begin with).

It really is a hard-core destination. No wonder most tourists who make it here do so merely because they are on a mission to visit every country on Earth recognized by the United Nations (not a mission I share). So I must have been quite an exception, having wanted to visit Nauru for what it is and its dark history and not just to tick it off a bucket list.

10 responses

Fascinating, thank you

thanks

Your blogs are always so informative and well-written. Thank you for making the effort to include all of us in your travels!

oh bless – thank you!!! It’s comments like this that keep me going!

Very interesting read – thank you!

thanks!

Newly discovered your site…and the existence of Nauru. Thanks for making me both consider it for a holiday destination, and then convincing me to stick to Spain 😉

haha 😉

Very well written and I subscribe to everything you said, especially “But I honestly do not think it’s a place I’d ever visit again.”.

I stayed in Nauru for about two weeks in autumn 2024 in the Menen hotel. Some of the rooms are sort of renovated and “decent” for a hotel in the south pacific. They even have hot (yes, hot!) water (although a little rusty in the beginning) in the shower.

If one could summarize the attitude in one word, it would be “whatever”. While being friendly, most people just don’t care. Although, as always, there are a exceptions to that.

The amount of traffic on the island is also astonishing – given the amount the roads the island provides.

Restaurant tips: “Crystal Kitchen” and “The Bay” (both on the Island Ring Road in the southeastern part).

Ah! And don’t bother to try to get to the Nauru Lookout Tower ;). It no longer exists.

Given all that: the island does have some potential but IMHO it’s still a looooong way. According to Nauru Airlines visitor numbers are going up significantly. We’ll see…

thanks for the comment. What did you do for two whole weeks on Nauru?!? I had run out of things to do after just a couple of days. Ate at the “The Bay” twice, though. And yes, the “whatever” attitude is a good description. “island time” is another. My guide was good though. Where can you find visitor numbers that are up to date I wonder …