As I had half announced in the latest DT Newsletter, here’s a Blog post about the Sered Holocaust Museum, which I visited in late October this year.

The museum is housed in the original barracks of what was Sered’s labour/concentration camp in the Holocaust in Slovakia during WWII.

As is often the case on this Blog, the post is primarily a short photo essay with just essential information. For more substantial background info and more detailed descriptions of the museum (plus practicalities) please refer to the full-length new chapter about Sered and the Holocaust in Slovakia that’s already on my main website.

There were in fact several labour camps for Jews in Slovakia from ca. 1941 onwards. After the Slovak National Uprising in August 1944, which was quickly and brutally crushed by Nazi Germany (see Muzeum SNP), these camps became proper concentration camps, now run by the SS, and also served as transit camps for deportations to Auschwitz and other camps.

Most of these camps in Slovakia disappeared after the war, only the barracks at Sered survived (being used for other purposes for decades). During the socialist period, which lasted until the November 1989 “Velvet Revolution” in the CSSR, there was little commemoration of the Holocaust or Jewish victims in general. The preferred memorialization was that of brave communists and partisans glorified.

Since then things have changed a bit and a few years ago the Sered Holocaust Museum first opened to the public. It started with just a single exhibition in one of the barracks. Meanwhile five of these structures have been refurbished and four contain exhibitions, all with a slightly different angle. There’s a general Holocaust exhibition with a focus on the “Final Solution”, another on how anti-Semitism and the persecution of Jews panned out in Slovakia specifically, another one is about Sered itself when it was a labour camp, and yet another one focuses on other former camps in Slovakia and the National Uprising.

First of all, here’s a photo of the row of original camp barracks as they look today:

.

.

The very largest exhibit at this site is an original cattle car that was used in the deportation of Jews during the Holocaust in Slovakia, now placed (sans wheels) on open-air display between two of the barracks (same photo as the featured one at the top of this post):

.

.

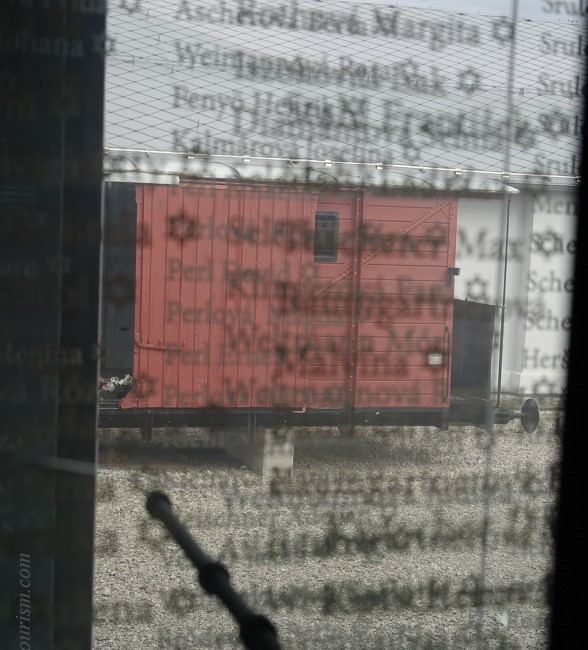

The first barrack’s exhibition features a “wall” of victims’ names etched on to glass panes partly in front of a window through which you can see the deportation railway car outside. This invited creative photography to me. Here’s an example:

.

.

Artefacts on display in the exhibition included a few predictable types of items, such as these:

.

.

Shoes, and especially children’s shoes, are indeed a typical type of exhibit in many a Holocaust exhibition, sometimes amassed (as in Auschwitz and Majdanek), sometimes more individual pairs, like here.

Stacks of victims’ suitcases are another “trope” of Holocaust exhibitions, and this is also to be found at Sered:

.

.

Also to be expected is the display of at least one of the infamous blue-striped garments inmates had to wear in concentration camps:

.

.

Equally predictable are displays of those yellow stars Jews had to wear to mark them as Jews. The Sered museum has several on display; here is one of them:

.

.

What I thought really set the Museum at Sered apart from most of its equivalents elsewhere was the life-size reconstructions of the interiors of the labour camp that you can see in the third of the barracks. This includes a faithful representation of what the living quarters of female inmates looked like:

.

.

Also reconstructed were several workshops, like this one for female seamstresses:

.

.

Workshop reconstructions more likely representing those for male inmates included ones for joinery, metalwork or making concrete pipes. Perhaps the most unexpected reconstructed “workshop” of sorts was this stack of rabbit hutches, one even with a taxidermy resident:

.

.

The explanation is that Angora rabbits were indeed bred for their fur at several concentration camps, apparently including Sered (also e.g. at Neuengamme).

Perhaps also a bit surprising is this reconstruction of a small school classroom (they did indeed have children in the camp and apparently some form of schooling was allowed):

.

.

There are also various smaller items on display in this part, including some that belonged to the infamous camp commandant Alois Brunner, who had already seen to the deportations of Jews from Austria and Greece, and later was commandant of the Drancy transit camp in Paris, before being sent to Slovakia to finish off the remaining Jews there. On display are a suitcase with his name on it, his hand-wash basin, and two of his walking sticks, which allegedly he often used to pull individual victims out the line at selections:

.

.

The grimmest artefacts on display are in the final barrack with the general Holocaust/“Final Solution” exhibition, especially this little jar containing a specimen of tattooed human skin of a victim:

.

.

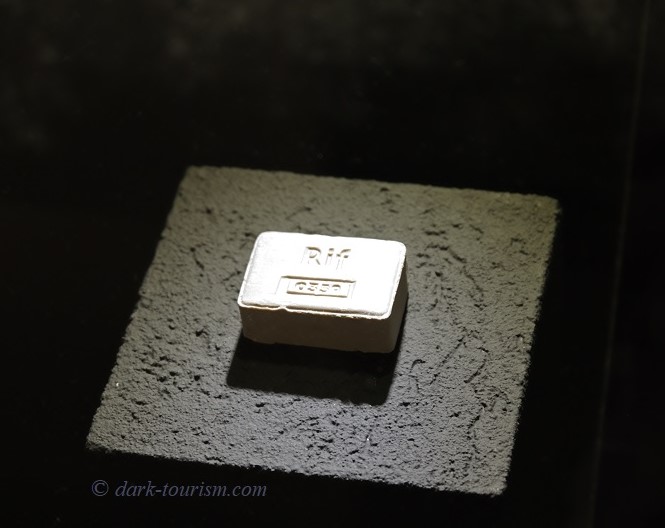

Also in this section was a block of soap from the Ravensbrück concentration camp in Germany:

.

.

But so much for a few visual impressions of the museum.

Sered is now certainly one of the most significant dark-tourism sites in Slovakia. I was positively surprised by the breadth of the coverage and the mix of visual elements with textual background information, some rather brief and basic, others in great detail. I spent well over two hours at this site and it could have been much longer had I watched all the videos that were screened at the museum too. But I was a little pressed for time, so I only watched the main part of the general intro film in the foyer. I also did most of my reading of the text panels later at home from the photos I specifically took of them for such later research (I often do that to speed things up at a given site – and it also helps with my photography if I don’t have to do all the reading when there).

It might be interesting to return to Sered in a few years time to see if the fifth barrack will also be given yet another exhibition (as was indicated to us at the museum reception). But it’s already quite impressive as it is now and deserves to be better known.