A week ago I came back from my two-week trip to Poland and Germany. One key element of this trip was to revisit Sobibór. Of the three sites of the Operation Reinhard (and “Final Solution”) death camps in eastern Poland, Sobibór had long been the most neglected, despite the famous revolt there in October 1943, which has twice been turned into a movie. In recent years, however, the Sobibór site has been totally transformed. First it was closed to the public for a number of years while comprehensive archaeological digs were undertaken. Then a brand-new museum was constructed that replaced the rather meagre older predecessor. This new museum (run under the auspices of Majdanek) opened in October 2020. So it was time for me to travel there again to see it for myself and check what else has changed since my first visit back in March 2008.

I’m currently also reading “Escape from Sobibor”, the book from the early 1980s that was the basis for the British TV film of the same name. When I’m done with that I have to substantially rework, expand and update the Sobibór chapter on my main website. But I can already give you some photos here on the blog and a brief update on what has changed at the Sobibór site, as a kind of preview. Here we go:

As far as the open-air parts of the memorial site are concerned, the main change is that the former site of the gas chambers, mass graves and cremation pyres, what was referred to as “Camp III” back in 1942/43, has been drastically transformed:

Compare this to an old photo I took over 13 years ago:

As you can see, several trees have been felled, the mother-and-child statue has disappeared (I later found it in the yard behind the museum – see below) and the main stone monument is ringed by a fence. The reason for this, as I deduced from the museum, is that this is the site of the gas chambers. During the archaeological digs some remnants of the foundations of these gas chambers were found. Whether these may be incorporated into any future commodification I don’t know. But for now visitors can no longer step on to that area, as had been the case before – in the photo above the benches on the right would have been directly on top of the gas chamber foundations. This has clearly (and rightly) been deemed inappropriate, so they are gone too now.

The biggest change here, however, is the disappearance of the mound-of-ash monument that stood atop the mass graves, as seen in this old photo:

Now the whole area is covered by a field of whitish stones and gravel, presumably concealing the old monument – or maybe that was removed before the reconstruction (same photo as the featured one above):

There are now also signs on the perimeter of this area prohibiting you from entering it. In fact I was lucky to get even this far, as nominally the open-air parts would have been closed to the public again from 16 August and fenced off entirely, but when I got there on the 17th the workers had yet to arrive so I was still able to explore. That way I also got to see the row of a good dozen information panels along the path leading to the main memorial. These provide a general overview of the history of Sobibór, like a small-scale open-air museum.

But the main reason why I came back to Sobibór was the brand-new museum. This is housed in a slick, modern, single-storey building:

I hadn’t seen the old museum – as that was closed at the time of my first visit – but it was clear from the size difference of the buildings that this new one would be a much more elaborate affair. I had also attended a seminar here in Vienna a few years ago, when the archaeological digs were still in full swing and plans for the new museum were being made. The previous curator of the museum gave a talk and it was clear that big changes lay ahead. Now I had a chance to inspect this new museum for myself.

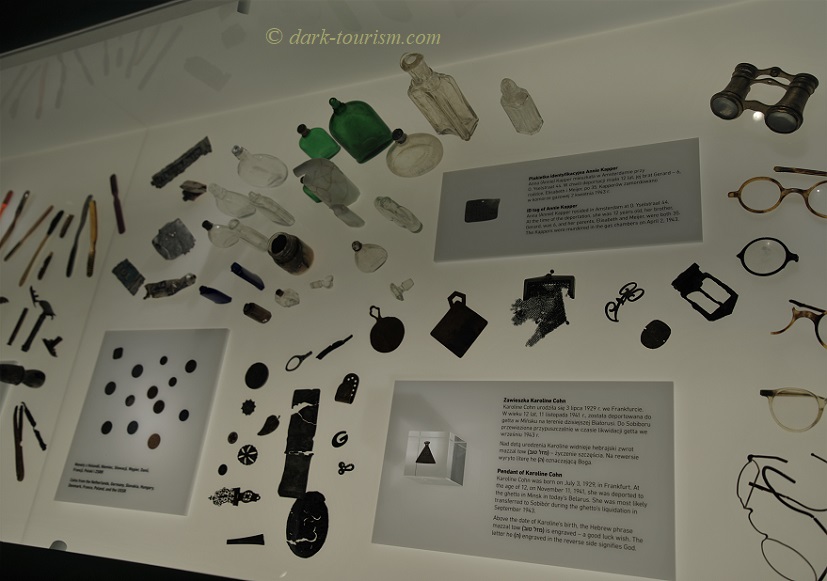

In addition to the usual text-and-photo panels and a few interactive screens and audio points, the main feature is a long glass display case that runs through the entire exhibition space, separating it into two halves, and you visit sections of it from both sides during the circuit through the exhibition. It thus forms the core of the museum. In it are displayed various items retrieved from the site during the extensive archaeological digs:

I found it quite astonishing how many personal belongings of victims could still be found at the site:

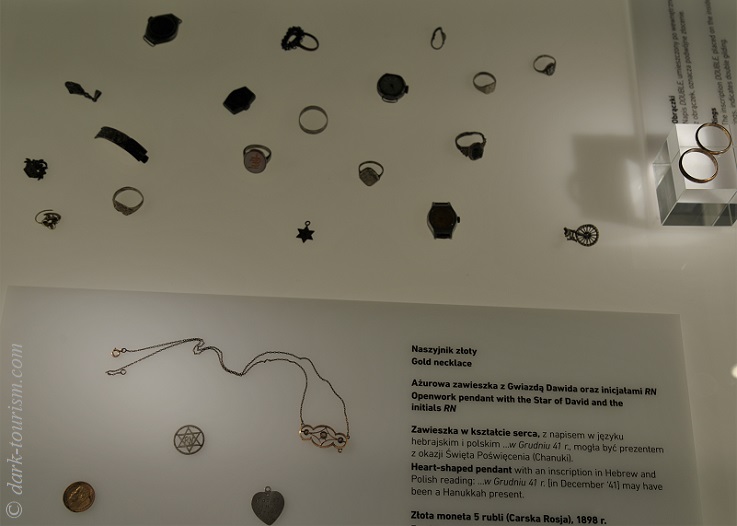

Most remarkable I found the items of jewellery – given that the victims were usually stripped of everything they had before they were sent to the gas chambers, and in particular valuables would have been robbed by the SS. But apparently quite a few items remained undiscovered. Maybe victims had thrown them away, maybe the Jewish workers who had to sort through the belongings hid a few items in the ground instead of handing them over to the Nazis (which would have been considered acts of “sabotage” that carried the risk of immediate execution had they been caught in the act).

In addition to such items from the victims, the digs also unearthed a few items that obviously belonged to the perpetrators, such as these pieces featuring Nazi insignia:

Also on display are some of the bullets and casings found in the ground that were most likely used in the shooting of victims:

Not all victims were gassed, those who were selected for work were often shot dead instead when had they been found guilty of any wrongdoings … or just on the whim of one of the sadistic SS men. Those from the arriving trains who were too weak or ill to walk to the gas chambers were often taken to an alleged “hospital”, which actually was an execution site, where they were then shot.

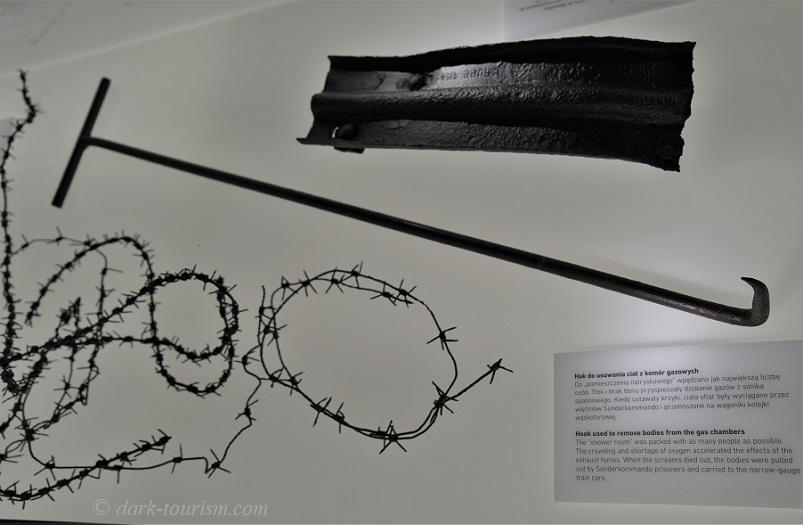

But the very grimmest exhibit in the display case I thought was in this part:

The metal hook seen here was used by the “Sonderkommando” Jews who had the gruesome task of emptying the gas chambers after each batch of victims. The bodies would usually have become totally intertwined and so such metal hooks were used to separate the corpses and drag them out. The piece of metal next to this corpse-retrieving hook is a part of the narrow-gauge rail tracks that led from the ramp to the gas chamber and mass graves / cremation pyres behind them. This rail track was used to transport victims to Camp III who were already dead on arrival along with those shot on the ramp. The blackened barbed wire must have been from the fence around the camp.

On display are also three wooden poles with remnants of barbed wire attached that must have formed part of that camp fence too:

An exhibit between the first and second half of the exhibition is a large scale model of the camp showing its layout as it would have been in early to mid 1943:

On the bottom far right is the railway ramp from where the victims were led to the first barrack, where they had to deposit all their luggage (to keep up the deception that they were merely being transferred to a labour camp, they were even issued with retrieval tokens for each piece of luggage). The yard beyond was the undressing area. Victims were told they had to take a disinfecting shower so they had to discard their clothes (again, retrieval tokens were issued for each bundle) and then they were herded in batches down a narrow corridor with fences on both sides that bent slightly to the right, so that its end was not visible from the entry point. This was referred to as the “Schlauch” (or ‘hose’). At a small barrack towards the end, women’s hair was sheared off, then the Schlauch led straight to the gas chambers where the naked victims were packed as tightly as was possible inside, the doors were sealed and the tank engine producing the lethal carbon monoxide gas was started. The two barracks next to the gas-chamber building were for the “Sonderkommando” Jews who had to clear out the gas chambers afterwards and then search the corpses for gold teeth or hidden valuables (in orifices). This whole complex was “Camp III”.

The three larger barracks in between the Schlauch and Camp III were for sorting victims’ clothes and luggage. On the left of the Schlauch was Camp II with warehouses and workshops and behind that, beyond the central watchtower, you can see a bit of Camp I where the barracks for the worker Jews were. The SS quarters are not visible in this image – these would have been to the left of the frame, right by the railways sidings.

After visiting the museum I also went into the yard behind it where I had spotted the old mother-and-child statue, which had been placed here temporarily:

The only original structure of the Sobibór camp that still survives to this day (the rest was razed to the ground after the camp was closed following the October 1943 revolt) is the railway ramp and spur that lead off the main tracks (which connect the provincial towns of Chełm and Włodawa).

The station building on the other side of the main rail tracks is, so I was told, also still original (but had clearly seen some refurbishment in recent years):

Whenever I spot non-smoking signs at a site like this, I find it rather odd. I have also seen such signs at the crematoria in Mauthausen and Stutthof! I’m normally all in favour of non-smoking rules, but at such sites they take on a certain irony …

The rusty station sign I saw by the tracks in 2008 has meanwhile been moved into the museum exhibition:

By the way, I’ve found out on this visit to Sobibór that the two photos in my forthcoming book (see the latest DT Newsletter!) illustrating this place are both now outdated, as one shows that old rusty sign and the other the former mound-of-ash monument. Oh well. Other places will change too. That’s the advantage of a website over a book – that it can always be updated later, whereas a book, once printed, is what it is. But it’s still nicer to leaf through a physical book …

But back to Sobibór, and one final photo:

In the overgrown area south of the museum and the railway spur some foundations and remnants of the outer fence can still be seen, as a local guide pointed out to me (I wouldn’t have stumbled upon these on my own – or known what I was looking at). The sign on the right points out the southern perimeter of the memorial site. This is where Camp I and the SS compound would have been.

But so much for Sobibór.

With 19 photos and nearly five pages’ worth of text it’s become one of the longer blog posts – this is also to make up for the previous three weeks without any new posts.

Next I will post more from my latest travels and then I think it may also be time for another theme poll …

But this is it for now.

2 responses

I visited Sobibor in 2017 and it looked the same as your 2008 photos except there was some digging going on. I will now go back and re-visit it again. Thank you so much for all of your blogs but especially this one.

Thanks – and yes, it’s all very recent developments. Certainly worth a re-visit now (or in a year’s time when the additional archaeological digs have finished). It seems to have helped that they’ve put Sobibor under the administration of the Majdanek State Museum (just like Belzec).