This is the second blog post derived from my recent week-long trip to Albania (see the previous post about Tirana). During that week I had also booked a day excursion with a driver/guide to the former ruined Spaç prison.

Under the long communist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha, Spaç was one of dozens of political prisons and forced labour camps dotted all over the country. It was set up in such a remote location that the prison designers didn’t even bother with a perimeter wall. And as I was told by my guide, one prisoner who did manage to escape, during winter, actually returned to the prison and gave himself up … rather than facing starvation or freezing to death in the rugged, largely unpopulated mountain terrain.

After the collapse of communism, Spaç prison was closed and has since suffered severely from vandalism and decay, even though in 2007 it was declared a national monument. But it lacks protection. In fact I first came across the site via the World Monuments Watch website (external link, opens in a new tab), where Spaç is listed as one of the most endangered such sites in the world. Some rudimentary stabilization work to save the remaining buildings from collapse was undertaken in 2017, and a few bilingual (Albanian and English) information plaques have been put up, but overall the site lacks proper commodification and interpretation. So it’s best visited with a guide.

And when I found a tour company (North Albania Tours, based near Shkodër ) that advertised such a tour, this instantly became my top priority for a return trip to Albania (in 2011, when I was first in the country, I did not yet know about Spaç). The tour wasn’t cheap, but worth it.

Access has been made easier thanks to a new dual carriage road through the mountains, so that only the last few miles have to be navigated on an unpaved, rough mountain road. Driving time from Tirana was thus ca. two hours.

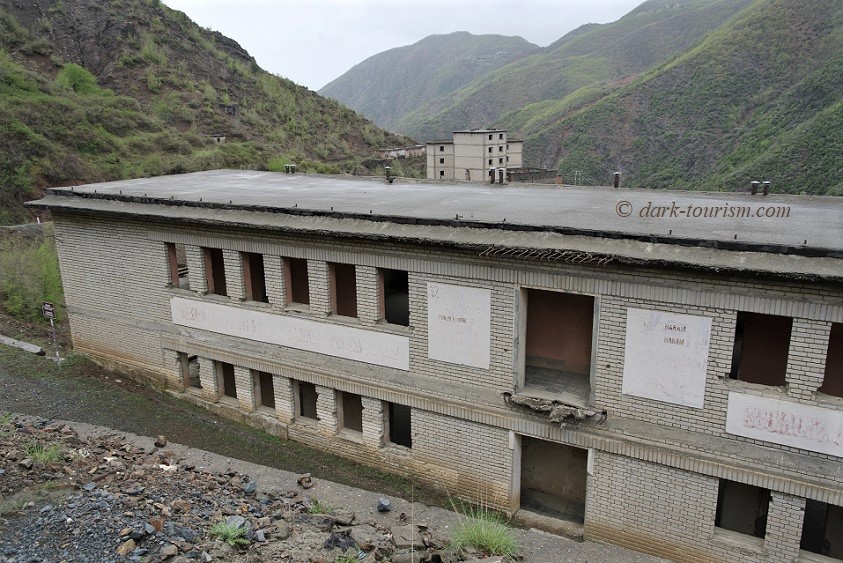

The first thing you see of the Spaç complex is this:

This was actually housing for the “free labourers” who were employed at Spaç for work in the adjacent mine that the prisoners had to do forced labour in.

From here you can see the terraced complex that was the actual prison … and the current mine, commercially extracting mostly copper, on the hillside behind:

The road below the prison is one of those leading to the various entrances to the mine inside the mountain.

Also at the southern end of the Spaç complex is this weathered plan of the site, also bilingual but barely legible any more:

We then drove on to the actual prison part. This was the administrative tract – with communist slogans on the outer wall that are even less legible now, almost completely faded away:

Within the prison complex at an upper terrace you find a lone and rusty tipping mine trolley. This is also the site where the isolation cells used to be (now demolished).

We then headed one terrace down, where there is this building, which used to have a mixed function (including serving as an infirmary) and which has been partly renovated, with new windows and doors. These doors were locked but we peeked in through the window and saw rows of benches or pews – so presumably this is where occasional memorial services or other events take place:

At the lowest terrace level we came to the former roll-call square and next to it stands the imposing main former cell block, seen in this super-wide-angle image (same as the featured photo at the top of this post):

Here you can see the stand-in measures taken to keep the building from collapsing. Note also the missing handrails – all taken away by looters for scrap metal. The right-hand-side wing has these wooden supports:

We used one of the staircases – with care – to get to an upper level:

The cells, which once held up to 54 prisoners each in multi-tiered bunk beds, are all bare now, save for the metal support columns that have been installed everywhere:

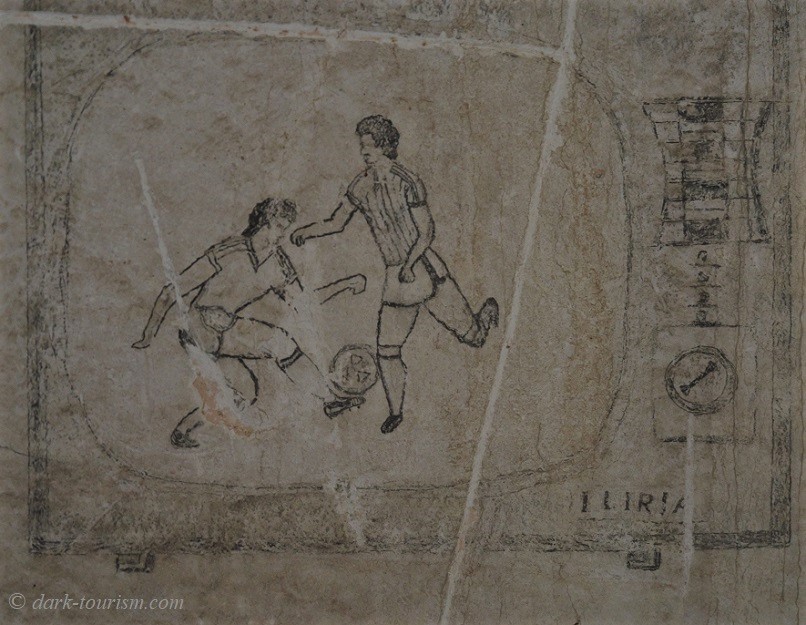

Our local guide, however, pointed out some doodles on the walls left by prisoners, including this rather elaborate example:

Note the word “Iliria” on the TV set – that was the make actually produced within Albania during the communism era.

Football also features in other doodles left behind, but that was clearly not all that was on prisoners’ minds, as evidenced here:

Note the year on the crude rendition of a football trophy (maybe it’s supposed to be the FIFA Wold Cup?). It says “1990”, so this must be from the final days when the prison was still in operation, just before the fall of communism.

Going from cell to cell on the outer galleries along the upper floors was a bit precarious, so we had to proceed with great care, as you can guess from this image:

In the bottom right corner of this photo you can see the ruins of what was once the prisoners’ latrines.

Eventually we made our way back to where the main gate of the prison part would have been, with a guard checkpoint and everything. The building on the right with the big hole in it used to be the visiting room, where relatives of prisoners could meet their loved ones for 15 minutes in the presence of a guard – hardly any privacy …

The building in light-coloured bricks opposite the checkpoint and visiting room was the administrative block. We also entered that:

In one room at the far end we discovered a wooden bed, complete with a woolly blanket, as if somebody had been squatting in here:

And finally here’s a view through one of the administrative block’s missing windows affording a view over the mountain scenery with the free workers’ housing block and the mining road below:

As you can see this really isn’t much of a tourist site, and indeed our guide confided that my wife and I were in fact only the second set of foreign visitors he’d ever taken here. As a memorial site it is also still seriously underdeveloped, though some welcome first steps have been made. There are in fact grand plans in the pipeline. The organization who, with support from the Swedish embassy in Tirana, saw to the initial stabilizing efforts and crude signage/text panels have a big master plan with detailed suggestions for improvement, including the addition of a proper visitor centre, toilets and other infrastructure, as well as a partial reconstruction of the first upper floor of the cell block (with rebuilt handrails and some doors and windows brought back). You can peruse the 70-page plan online at this address (external link, opens in a new tab).

But in reality, nothing much seems to have happened in the years since 2017. Still for people like us who also enjoy a bit of urbex, this was a totally worthwhile visit. It will also be the topic of the first new Albania chapter for my main website, which will also feature more historical background and a larger photo gallery. I just got a bit distracted by other things (as I will explain in the next DT Newsletter – you can sign up in the top right corner of this page), so I haven’t yet got round to that. But bear with me. It’ll come soon. This blog post is basically just a taster …