On this day, 76 years ago, in the early hours of 21 July 1944, Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg was summarily executed by firing squad in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock building in Berlin, together with some of his co-conspirators.

Their plot, code-named “Operation Valkyrie”, had been to assassinate Adolf Hitler at his command post of Wolfschanze (‘wolf’s lair’) in what today is in north-eastern Poland (then German East Prussia).

Stauffenberg, thanks to his high rank in the military, had access to Hitler, and so it was decided that he would plant a bomb hidden in a briefcase near Hitler during a meeting at Wolfschanze. Stauffenberg was to leave the briefing early and fly back to Berlin from the Wolfschanze airfield and once Hitler was dead, the conspirators would take over the leadership. The aim was primarily to save Germany from total destruction in the war (but to retain military rule). Unlike Hitler, Stauffenberg and co had already realized that the continued war effort had become futile.

However, during the briefing at Wolfschanze on 20 July 1944, the briefcase placed under the conference table by Stauffenberg was later moved by one of the participants in the meeting so that when the bomb blew up, Hitler wasn’t so close to it any longer. And so it came that he survived, only slightly injured, as he had been shielded by the heavy conference table. Four others in the briefing were killed, however, and everybody in the room suffered injuries. Yet the main aim of the plot had failed.

Unaware of this, Stauffenberg arrived in Berlin at the Bendlerblock military offices, where the second phase of the coup was to be initiated. But instead Stauffenberg and his co-conspirators learned over the radio that Hitler had survived. One of the conspirators, to save his own neck, switched sides again and a court martial was staged at which Stauffenberg and the other ringleaders were, predictably, sentenced to death.

The spot where the execution took place in the first hour of 21 July 1944 is today marked with this plaque and wreath. The plaque gives the date of the event and the names of the five executed here and the inscription above, “Hier starben für Deutschland”, translates roughly as ‘they died for Germany here:’.

Also in the courtyard is a statue of a resistance fighter that is said to somewhat resemble Stauffenberg’s features.

Moreover, the Bendlerblock is also the location of the German Resistance Memorial Centre (“Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand”). In its elaborate permanent exhibition one can learn not only about Stauffenberg’s plot but also about the many forms resistance against Nazism took, including other assassination attempts, e.g. that by Georg Elser much earlier, during the earliest phase of WWII, in November 1939, also by a secretly planted bomb, which however also failed. Elser, who was murdered at Dachau in April 1945, had been a man of “proper” resistance to Nazism in general. Stauffenberg, in contrast, had been an ardent participant in Nazism and WWII, and only became critical of the war effort after Stalingrad.

At the site of Stauffenberg’s assassination attempt, now in Poland, another memorial plaque (in Polish and German) marks the spot where the building stood in which the bomb went off.

The Wolfschanze HQ was given up in November 1944 as the Soviet Red Army advanced westwards. The massive bunkers were blown up, but several were so solid that the explosives had little effect on them. And so, at the memorial site today you can still see big, brooding concrete monsters, overgrown with moss, in the middle of the Masurian forest. Here’s an example:

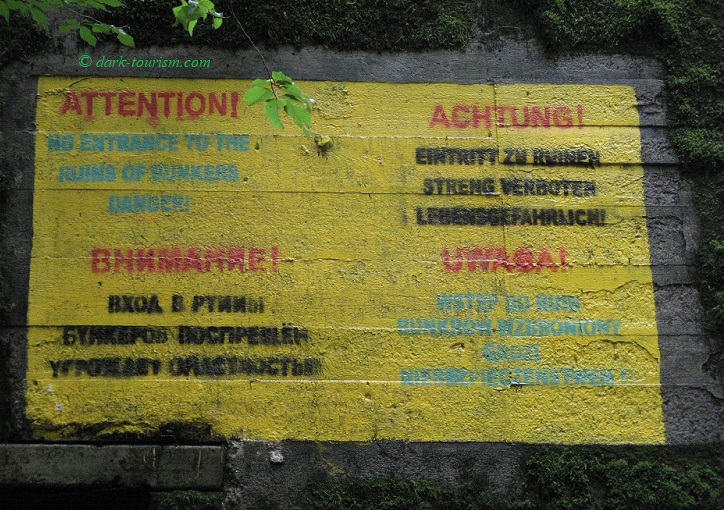

The yellow sign visible in the photo above is a warning admonishing visitors not to enter any of the bunker ruins, here’s a close-up:

Despite these warnings, visitors do enter the ruins quite routinely, as seen in this picture:

I have to admit that of course I, too, went against the signs and entered some of the bunkers. Here’s a photo I took inside one of them:

My favourite photo from Wolfschanze, however, is the following one – where the sticks placed against the big broken concrete block look like they are actually supporting it and keeping it from falling over completely (but that’s of course only an optical illusion).

Wolfschanze is a strange place to visit in some ways. On the one hand, dark history hangs heavy over these massive relics, but the commodification also has its dodgy elements. In the summer, bike rides on historic Nazi-era motorcycles are offered, and the souvenir shop on site has many items on sale that some may find questionable – e.g. mock hand grenades with a picture of a wolf on, or little metal skulls with Wehrmacht helmets and such like.

Amongst the visitors are also some that make you wonder about their motivations for coming here, especially some of the bikers in military fatigues and leather vests with big wolf images on the back. There’s also graffiti … and yes, that does include the occasional swastika!

On the other hand, during my visit to the site I also spotted a group of young German Bundeswehr soldiers, in uniform, apparently on an organized tour of the site as part of their political/historical education. I wonder what narrative they were given by their instructor …

2 responses

Here is an interesting site for Dark Tourism archives. It’s the Oekumenische Marienschwestern near Frankfurt, a community founded by 2 German women after WW2 in an attempt to compensate morally for the crimes committed during the war by practising chastity, poverty and discipline, in a way rediscovering the monastic concept in the Lutheran world. I have no idea where this would fit in the Dark Tourism concept but it’s an interesting act of reparation sustained over the years. Their itinerary is likewise interesting as the pan-religious welcoming.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evangelical_Sisterhood_of_Mary

indeed, not really dark *tourism*, at least not in the usual sense (though pilgrimages are sometimes seen as an early form/precursor of DT), but an interesting angle on what in German is called “Vergangenheitsbewältigung” (very roughly ‘coming to terms with one’s past’)