———————–

UPDATE: I know that most readers’ eyes will currently be on Ukraine/Russia; but I had prepared this post already on Monday/Tuesday, so I thought why not use it … I’m pretty much lost for words about what’s happening in Ukraine anyway. So here we go, with a distracting post about a little-known small country far away in South America.

———————–

On this day, 42 years ago, on 25 February 1980, the so-called “Sergeants’ Coup” took place in Suriname, led by the later military dictator Dési Bouterse.

Suriname is the smallest independent country in South America and is rather little known in the outside world – except in the Netherlands, where there is a sizeable Surinamese expat community. That’s because Suriname used to be Dutch Guiana, the Netherlands’ only colony on the Southern Cone of the Americas (they also still have colonies in the Caribbean, of course). This colony was released into independence in 1975. It was a turbulent time and eventually the military under Bouterse overthrew the elected government of Prime Minister Henck Arron.

The February 1980 event included the burning down of the central police station in the capital Paramaribo. At the site, a monument to the 25 February coup, incorporating the stumps of the front columns of the former police station, was unveiled in 1981:

The date was also declared a national holiday. And it is etched on to the bas-relief on the central part of the monument, as seen in this photo (same as the featured photo at the top of this post):

Depicted are some of the sergeants/soldiers who launched the coup (one does look quite a bit like Bouterse), though I have my doubts that they were really cheered on by flag-waving, skimpily dressed women …

The Bouterse dictatorship took on the familiar forms of repression of press freedom, curfews, and arrests of political opponents. Amongst the very darkest chapters of Bouterse’s dictatorship were the so-called “December Murders”, when on 8 December 1982 some fifteen opponents of Bouterse, including journalists, academics and lawyers, were abducted, taken to Fort Zeelandia in Paramaribo, tortured and eventually shot dead. This is the spot where the atrocity took place – now a memorial:

The holes in the wall you can see here are not bullet holes as such, but spots from where bullets were later retrieved from inside the wall for forensic investigation.

Another very dark episode of the dictatorship years was the Moiwana massacre, when in November 1986 Bouterse sent a death squad to the Maroon village of Moiwana in the east of the country. Their primary task was to capture Ronnie Brunswijk, the leader of the so-called “Jungle Commando”, who had waged a guerilla war against the government. The soldiers failed to locate Brunswijk but massacred at least 35 villagers, mostly women and children, and burned the village down. A memorial to this atrocity was unveiled at the spot in 2007:

When I was travelling from Paramaribo to French Guiana in August 2019, my driver-guide made a little detour to the bauxite mining town of Moengo where he pointed out a large mansion with a high fence around it and a guard tower and said that this was Ronnie Brunswijk’s house:

Brunswijk, interestingly, was originally a personal bodyguard for Bouterse, but in 1985 he fell out with his boss and formed the Jungle Commando, which was originally intended to fight for better recognition of the Maroon population (which goes back to African slaves who had fled and set up communities in the interior of the rainforest) but also fought against the military dictatorship in Paramaribo in general. A peace settlement was reached in 1992. Brunswijk was, like Bouterse, sentenced in absentia in the Netherlands for drug trafficking. Yet he remained a wheeler and dealer in Suriname and in July 2020 he became vice-president!

Dési Bouterse, meanwhile, remained as military dictator until the restoration of democracy in the early 1990s. In 2010 he achieved the remarkable feat of having himself democratically elected president. And as if that alone wasn’t astonishing enough, he was elected into office with the support of Ronnie Brunswijk’s party, whose seven seats/votes in the National Assembly secured Bouterse’s victory despite him having failed to achieve an absolute majority. He later used his presidency to grant himself amnesty from prosecution for the December Murders (see above!)

In 2015 Bouterse was re-elected for another five-year term. So when I was in Paramaribo in August 2019, he would have been resident in the capital’s presidential palace, pictured below:

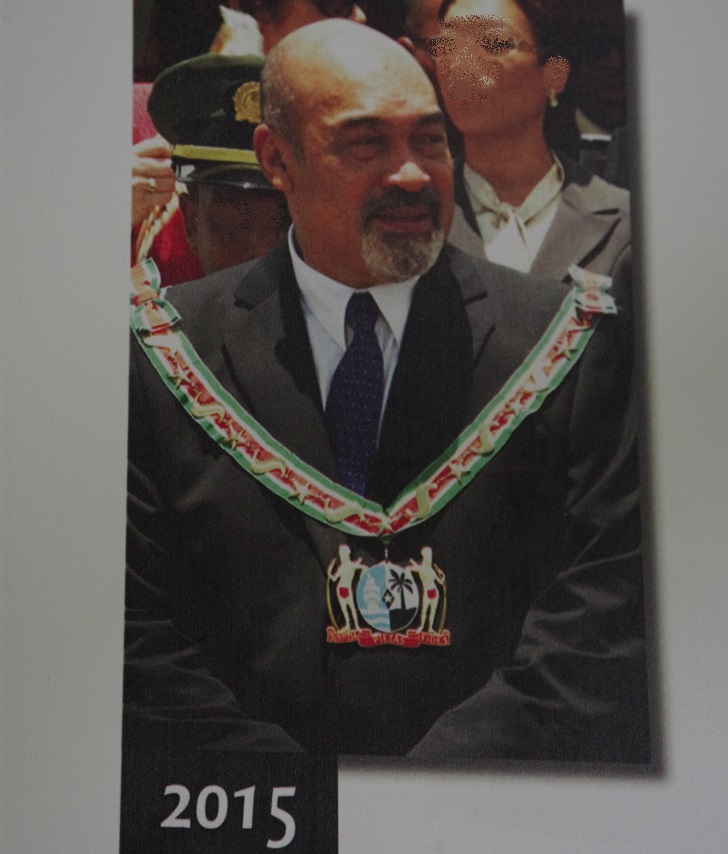

I also visited Fort Nieuw Amsterdam at the confluence of the Commewijne and Suriname Rivers. In the museum part inside, the timeline of Surinamese history ended in 2015 with this photo of Bouterse after his re-election as president:

In late 2019, Bouterse’s amnesty was overturned by a Surinamese court and he was sentenced to 20 years in prison for the December Murders. He appealed in January 2020 and in 2021 the 20-year sentence was upheld. But as far as I could find out Bouterse is still not behind bars. The latest I was able to dig up in the media was this Dutch RTL bulletin (external link, opens in a new tab) from September 2021 reporting that Bouterse was apparently “not worried” about the prospect of a prison term. He still has a powerful following in the country so will probably be able to weasel his way out yet again. However, as of June 2020 Bouterse is officially “retired” from politics. He was succeeded as president by Chan Santokhi, who was the sole candidate that year.

Following the May 2020 general election a four-party coalition was formed. The Surinamese parliament is called De Nationale Assemblée, or National Assembly, and has only 51 seats, so it’s not surprising that the building in which the assembly meets, isn’t particularly imposing:

But so much for our little historical excursion into a corner of the world that to so many people outside it is hardly known at all.

I admit that this also applied to myself until a few years ago when I started to pay more attention and study the tremendously interesting and truly chequered history of the three Guianas. This was helped a lot by the book “Wild Coast” by John Gimlette. It concentrates more on neighbouring Guyana but also has three chapters about Suriname, which provided me with invaluable insights into the history and politics of this country (covered until 2012, when the book was published). It also paved the way for my own trip to the three Guianas (former British Guyana, former Dutch Guiana, which is now Suriname, and French Guyane, which is an ‘overseas department’ of France). That was my last really big trip before the pandemic. In total I had a good two-and-a-half weeks in the three countries, which was an incredibly rich and diverse experience. Parts of this will no doubt feature in future posts on this blog. And one particular dark place in Guyana already had its own dedicated blog post here.