This is a theme that featured a couple of times as a candidate in theme polls on this blog (namely here and here) but failed to win on both occasions. I decided to feature it now anyway – inspired by the latest news and dramatic images from Indonesia, where there’s been a major ash eruption of Mt Semeru volcano on the populous island of Java (see e.g. this article from Sunday, more on Volcano Discovery).

I’ve been to Mt Semeru, or at least I got relatively close to it, namely when I was in Indonesia in 2014 and visited the famous Tengger volcanic complex. While watching the sunrise from the caldera rim I saw not only Mt Bromo’s gas plume puffing away from its crater but also Mt Semeru in the background, which at that time was emitting no more than a faint plume of smoke that drifted in the wind away from the cone, as seen in the featured photo above, repeated below (Bromo is on the bottom left, Semeru towering over the whole scene in the background):

Indonesia has more active volcanoes than any other country in the world, and on my 2014 trip to the region I saw about half a dozen of those. The most dangerous of the lot is the frequently erupting Mt Merapi, also on Java, another stratovolcano whose eruptions often involve pyroclastic flows and subsequent lahars. Here’s a photo of the summit of Merapi, partially shrouded by clouds (and no ash visible):

When I was there, I was taken on a jeep safari into the eruption zone where I saw a couple of destroyed villages, and we even drove into a lahar canyon, as seen here:

Lahars are mudflows that come about when heavy rainfall mixes the fallen ash from pyroclastic flows with water. These then surge downhill like liquid concrete burying everything in their path. Mt Merapi should be given the widest of births, really, given how hazardous it is. On the other hand, however, volcanic ash also has its virtues. To begin with, it comes with lots of minerals that make the soil around the volcano very fertile, so people take the risk of living close to its slopes to exploit that. Moreover, solidified lahars are a good source of high-quality raw material for making concrete, and as Indonesia is constantly constructing ever more high-rises and whatnot, it’s a valuable resource. We saw this at Merapi, where there was lots of mining activity going on. It had almost a gold-rush atmosphere. Here’s a photo showing the lahar mining:

Amongst the other volcanoes I saw in Indonesia was Ijen, also in East Java, which is mainly fabled for its nightly blue flames at the sulphur mine inside the crater on the edge of its acidic lake. Here the main hazard was not so much ash (although also present) but the acrid sulphurous gas plumes wafting around the sulphur mine. Hence I had to wear a protective mask. I don’t normally post photos of myself (let alone “selfies”) but I make an exception for this case; as photo proof, as it were:

Not in East Java (as a common error claims) but located to the west of Java in the strait between that island and Sumatra, is the most infamous of all of Indonesia’s volcanoes: Krakatoa. The original Krakatoa was of course blown to smithereens in the historic cataclysmic eruption of 1883. However, a new volcano cone has arisen from the waters in its stead and is also still active. In Indonesian it’s referred to as “Anak Krakatau”, or ‘Child of Krakatoa’. On my 2014 travels we went on a boat trip to this volcanic island at a time when activity wasn’t too high.

You can see the dark reddish brown of a recent lava flow, ash deposits and some gas/smoke venting at the top. We also landed on the island and hiked to the edge of the most recent lava flow, but climbing to the summit was not advisable because of the fumes and instability of the ground.

But back to ash. My first encounter with volcanic ash was actually in Japan, namely in the spring of 2009. My itinerary included several days on the southernmost of Japan’s main islands, Kyushu, which also has some of the most active volcanoes. Out of these I saw Mt Unzen from afar and Mt Aso close up. But the ash I saw came from Mt Sakurajima, which is on an island right opposite the city of Kagoshima in the south of Kyushu. Here’s the view you get of the mountain from the city.

While my wife and I were staying in a lovely private pension at the foot of Mt Aso, our host, who knew we were set to head to Kagoshima the next day, reported that he’d seen on the news that Sakurajima had just erupted and covered the city in a blanket of ash. Indeed, when we went out the next evening in Kagoshima we spotted cars still covered in a thin layer of ash, such as this one:

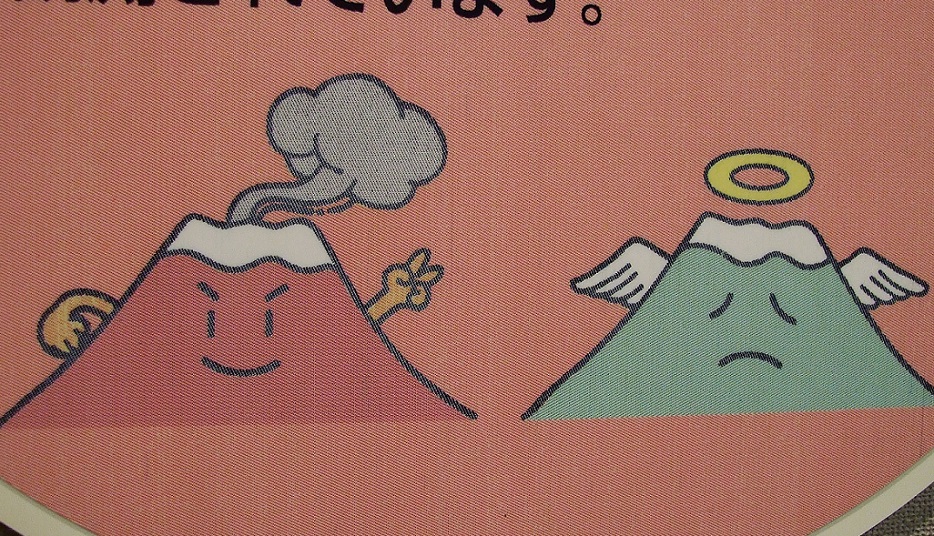

But by the time we got to Kagoshima, the eruption event at Sakurajima was over, most of the ash had been cleared away, and we were able to take the ferry across, hike a lava trail and visit the local volcano museum. My favourite exhibit was this (typically Japanese) cutesy image:

I guess it was intended to educate kids about the difference between a harmless non-active (dormant) volcano and an ash-venting active volcano that has to be approached with more caution.

The most dramatic volcanic activity I ever witnessed was at Soufrière Hills volcano on the British Caribbean island of Montserrat. When this volcano suddenly came back to life in the 1990s after a long dormant period it made the island’s capital Plymouth uninhabitable, and a large part of the population were evacuated (mostly to Britain); only the northern third of the island remained inhabited. And that’s where I stayed when I travelled to Montserrat in late 2009. The activity level was such that the entire southern two-thirds of the island were a total exclusion zone. But it was possible to view the volcano from the official Montserrat Volcano Observatory (MVO) located on a high slope opposite the volcano’s cone at a safe enough distance. I drove up to the MVO several times during my stay. And indeed the very first time I was up there I witnessed a massive ash-venting period and took this photo:

Shortly after I was lucky enough to witness a huge pyroclastic flow as the ash column above the volcano collapsed and the hot ash plume raced over the hillside and abandoned villages:

In fact the flow turned into a pyroclastic surge at one point, meaning the mass of ash and hot gas climbed over a hillside! Soon enough researchers working at the MVO came out with their cameras and tripods to take yet more photos of the activity:

On these occasions the usual wind blew the ash cloud in a westerly direction over the remains of Plymouth and towards the sea. On another occasion, however, the ash came down from right above us as a small group of us met at the MVO and so we had to take shelter inside for a while until the ashing had calmed down again (the activity followed a quite regular periodic pattern at the time). But with all that ash still in the air it was advisable to keep a mask on. I’ll allow myself a second “selfie” (unheard of! In a single post!!) showing you this:

Volcanic ash is something you really don’t want to breathe in. Note that this sort of ash is very, very different from the light fluffy ash you get from burning wood or paper. Volcanic ash, in contrast, is basically pulverized rock and thus very heavy and consisting of very tiny sharp particles that can do serious damage to your lungs. Such ash is also poison for aircraft engines, as we know from events such as the Eyjafjallajökull eruption on Iceland in 2010 which disrupted air traffic on a large scale. In fact when I travelled to Montserrat in 2009 I was forced to take the ferry from Antigua because Montserrat’s little airport had been put out of action due to unusual ashfall in the north of the island.

I also witnessed this myself, shortly after moving into our self-catering abode at Gingerbread Hill. We had just hung up some laundry to dry in the open air when we were warned by the family who owned the property that ashfall was approaching. Normally the trade winds preclude that but there were unusual changes in the wind from time to time then. We managed to rescue our washing and then stayed indoors while ash was raining down. Afterwards I had the task of clearing the ash layer from the veranda (wearing a mask, of course). I swept the bulk of the ash into a corner and put it in a plastic bag. When I then tried to pick the bag up the handles instantly broke. This taught me how heavy volcanic ash is. The amount wasn’t even so big, about the volume of a regular house brick, but at least twice as heavy. That’s why the accumulating ash on roofs is such a hazard and newly built houses on Montserrat often come with reinforced-concrete roofs for protection. I also learned about the destructive potential of these tiny particles when the new compact camera I had bought before the trip seized up shortly after I arrived back home in Vienna. Somehow, ash particles had even made their way into the inside of the lens! I’ve heard from specialist volcano photographers that they have to replace their camera gear at least every few months no matter how much they try to protect it.

Other than ashing and pyroclastic activity, the volcano was also spectacular to watch after dark, when you could see the red glow of the lava dome and lava bombs rolling down the volcano’s slopes:

As going to Plymouth, the former capital of Montserrat that is sometimes referred to as the “Pompeii of the Caribbean”, was impossible because of the level of volcanic activity, we at least took a boat ride to see it from the sea as close up as was allowed at the time. This is the apocalyptic scenery we caught a glimpse of:

In the case of Plymouth, the ash cover comes not only from pyroclastic flows and ashfall but also from lahars. Meanwhile only a few rooftops still protrude out of the ash layer in the former centre of Plymouth. But even houses on the higher slopes of the surrounding hills are uninhabitable due to all that ash. Our skipper on that boat trip, who had been to Plymouth several times when exploring it was possible, compared it to “walking into a Mad Max film set”. This would give me a reason for a return trip one day, when volcanic activity is low enough and I could explore this unique ghost town.

En route to Plymouth our boat also passed other settlements in the exclusion zone that had become uninhabitable and are now abandoned for good, such as these ash-greyed buildings:

One of these, so our skipper said, used to be the villa where Keith Richards stayed at the time when the Rolling Stones recorded their album Steel Wheels at the island’s former AIR Studios (at the time one of the leading studios in the world).

Leaving Montserrat and the Caribbean, here are a couple more volcanoes in the Americas, such as this one I spotted in the Andes in Chile (I think it was Mt Putana) with sulphurous fumaroles on the crater rim:

The best-known volcano in North America has to be Mount St Helens, though. Its 1980 explosion was the biggest volcanic event in the whole history of the USA. When this volcano blew its top a large area was completely devastated and ash fell on to eleven US states. Three and half decades later the mountain presented itself thus, when I visited in August 2015:

In the foreground you can see what is called the “pumice plain”, where millions of tons of ground-up volcanic rock were deposited, and in the centre of the capped crater you can see a bulge – this is the new lava dome that’s forming. So Mount St Helens is still active, but hasn’t erupted since 1980.

This post has been almost entirely about volcanoes and volcanic ash. But having come to the US, I can’t finish this post without covering a place that is actually named after ash. Here we go, this photo was taken in Ashland in Pennsylvania:

I have no idea what really happened to these house, but I remember quipping at the time that I reckoned somebody must have taken the town’s name a little too literally!

The reason I went to Ashland (see Centralia) in 2010 was to see its Pioneer Tunnel, a former anthracite coal mine that has been opened to the public on guided tours. Being deep inside a mountain certainly had a dark appeal … but that’s for another post. Maybe I can do a theme post on “DT & mining” next …

2 responses

Awesome blog this week Peter. I loved the volcano photos and would love to see a blog on

DT & mining.

thanks! Yes volcanoes are awesome – if destructive. I’ll look into DT & mining later this week …