Contrary to the announcement in last week’s post that that would be the last one of this year, here’s another one, posted from Vienna (a hint that might answer a few tacit questions I don’t want to bring up myself).

Today is the day after Christmas Day, referred to in Britain (and some of its former colonies) as “Boxing Day”. Last year around this time (on Christmas Eve) I brought you a post about “Dark Tourism & Christmas”, and that more or less exhausted the theme so I can’t do that again. But with a bit of lateral thinking applied, I derive from “Boxing Day” another unusual theme: Dark Tourism & Boxes. Here we go:

The sort of thing some of you may think of first in the context of boxes and darkness will be “wooden boxes” such as these:

This photo was taken at the unique Sepulchral Museum (museum of funeral culture) in Kassel in Hesse, Germany. It shows a whole range of different styles of coffins, from literally a simple wooden box, to a classic Islamic coffin, a futuristic modern-day coffin and several richly decorated coffins from days long gone by.

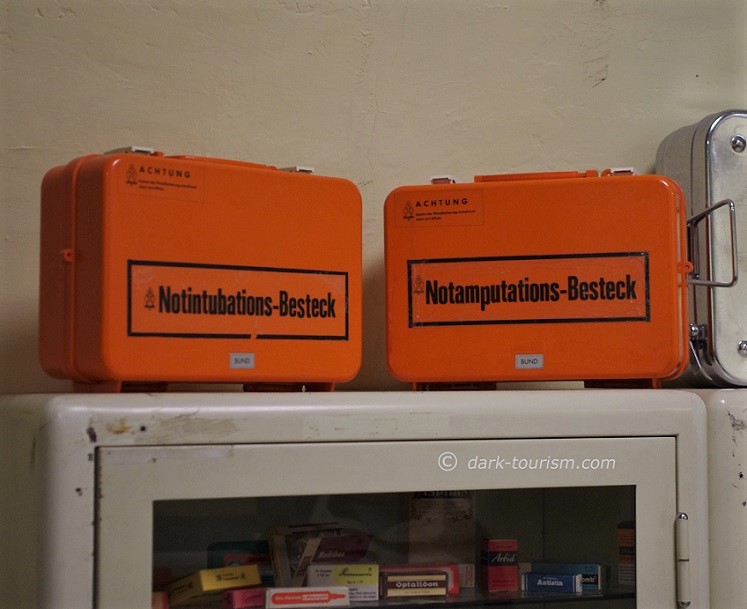

Another type of box often encountered in the context of dark tourism are medical kit boxes, which feature routinely in war museums. This photo of such a display was taken at the Spanish Civil War museum in Fayón, northern Spain:

The next photo featured before on this blog, namely in the medical theme post in June of this year:

This was taken at a Cold-War-era facility, namely the former West German government bunker at Marienthal near Ahrweiler (a place that was in the news more recently for quite different dark reasons: the catastrophic flooding last July).

And one more example of medical boxes, now open, showing the contents:

This photo was taken at the Passchendaele 1917 Museum near Ypres in Flanders, Belgium, one of the several eminent World-War-One museums in the region.

Another type of box often encountered at museums like that are boxes of ammunition, such as this one from, again, the Spanish Civil War, taken at the 115 Days Interpretation Centre in Corbera d’Ebre:

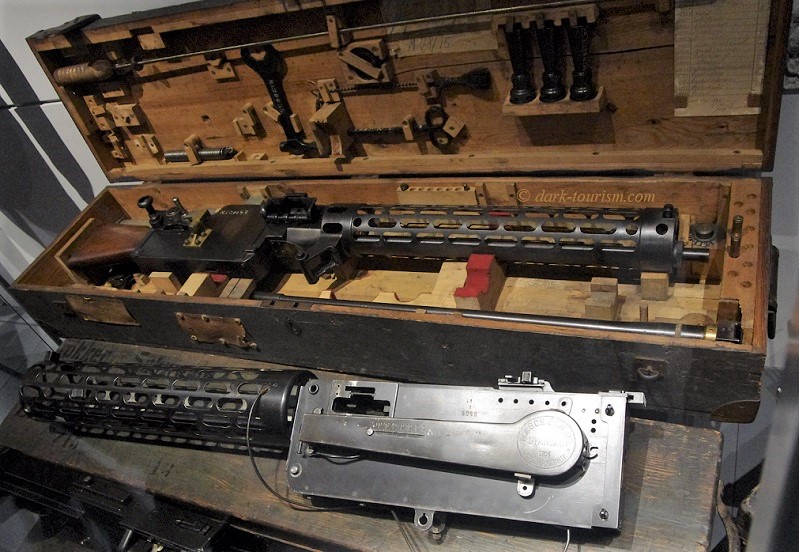

Weapons also often come in boxes, like this heavy machine gun from the First World War, on display at the Military History Museum here in Vienna:

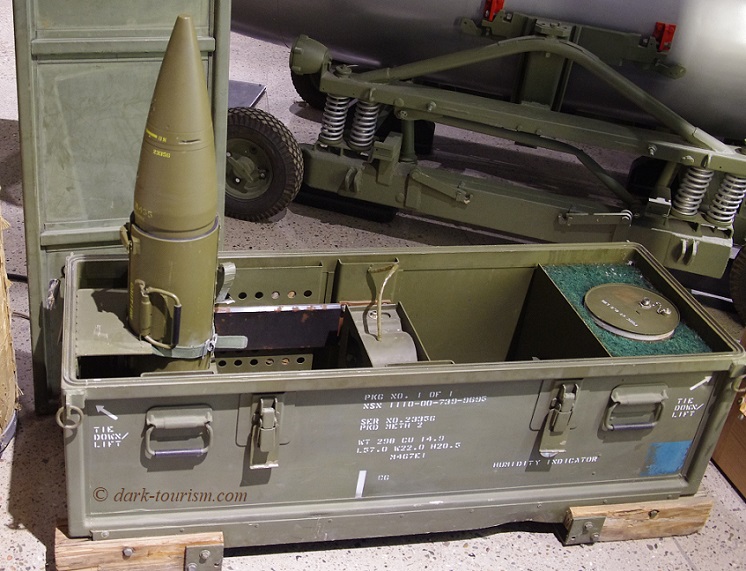

Even Cold-War-era nuclear weapons sometimes came in boxes, such as this small-atomic-bomb-carrying artillery shell, a mock-up on display at the Museum of Nuclear Science and History in Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA:

Bigger nuclear weapons typically sit atop missiles, like the massive Titan II ICBM, which used to be equipped with the largest nuclear warheads in the US atomic arsenal. The Titan missiles and their silos were decommissioned in the 1980s and today only a single one survives and has been preserved as a memorial and museum of sorts, namely at Sahuarita near Tucson, Arizona, USA. On tours of the launch control centre you also encounter the red code box in which the launch codes were kept under lock and key, only to be opened by the missileers on duty in an actual alert, i.e. at the start of World War Three. So, arguably, this is perhaps the darkest of all boxes, at least potentially:

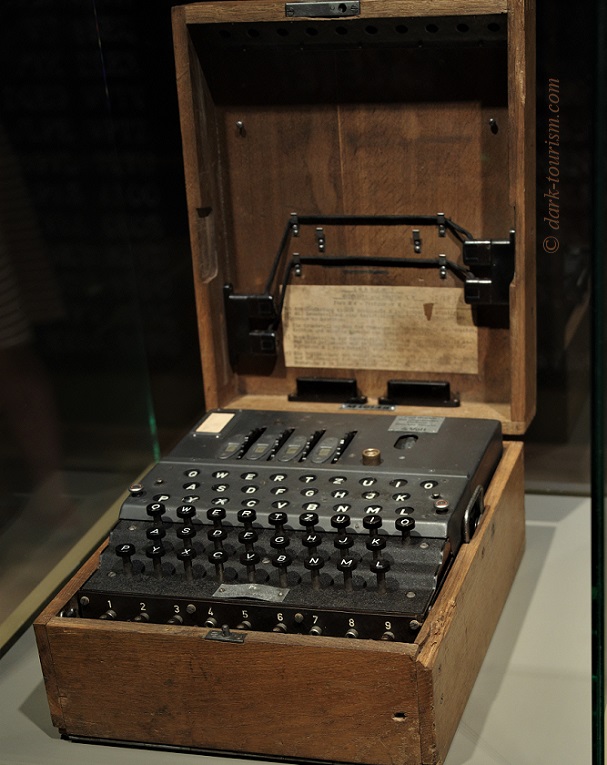

Speaking of codes, the legendary WWII-era German Enigma encryption machine, whose code was famously broken by the mathematicians at Bletchley Park, Great Britain, also came in a wooden box:

This particular specimen of this mass-produced machine is now on display at the WW2-Museum in Gdańsk, Poland.

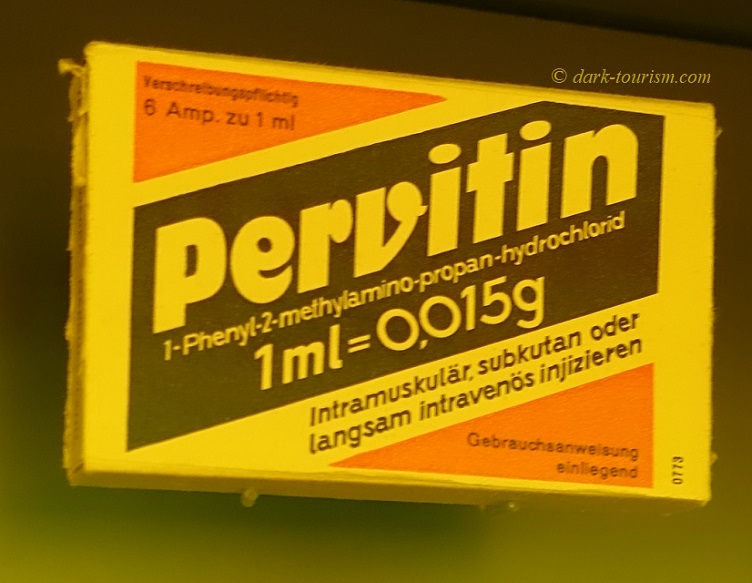

But back to the medical side of war. This includes not only field hospitals and their gear to “repair” soldiers. The pharmaceutical industry has also provided performance-enhancing drugs for the military. In the early phases of WWII, especially in Germany’s “Blitzkrieg” against France and during the Battle of Britain, millions of doses of “Pervitin” were dispensed. It’s a drug based on methamphetamine (aka “crystal meth”) and could keep tank drivers or bomber pilots awake and alert for days (but had severe side effects in the longer term and hence its use was later scaled down). Here’s a box of Pervitin on display at the German Technology Museum in Berlin:

Another kind of “drug” of a less severe sort was pushed in World War One: tobacco, especially in the form of cigarettes. Sent to the trenches and battlefields on a massive scale, it ensured that the tobacco industry would have millions of cigarette addicts, i.e. customers, after the war when the surviving but often traumatized soldiers returned to civilian life. Here’s a photo taken at the Hooge Crater Museum in the Ypres Salient, Belgium:

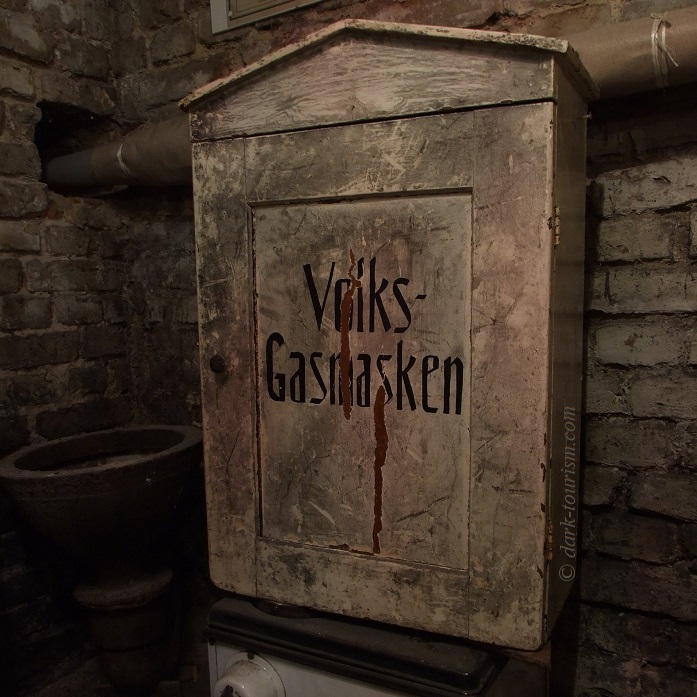

And speaking of airborne poisons, it was also in WW1 that the use of poison gas as a weapon was “pioneered”. It played a far less important role in WWII, but the fear of gas remained a constant in the background, and even civilian air-raid shelters were sometimes equipped with boxes of gas masks, such as this one:

The word “Volksgasmasken” translates roughly as ‘people’s gas masks’. The world “Volk” was a standard Leitmotif in Nazi Propaganda (cf. also “Volksempfänger”, the radio for the masses, or the legendary “Volkswagen”, also first developed in Nazi times). This photo of a gas mask box was taken at the Anti-Kriegs-Museum in Berlin.

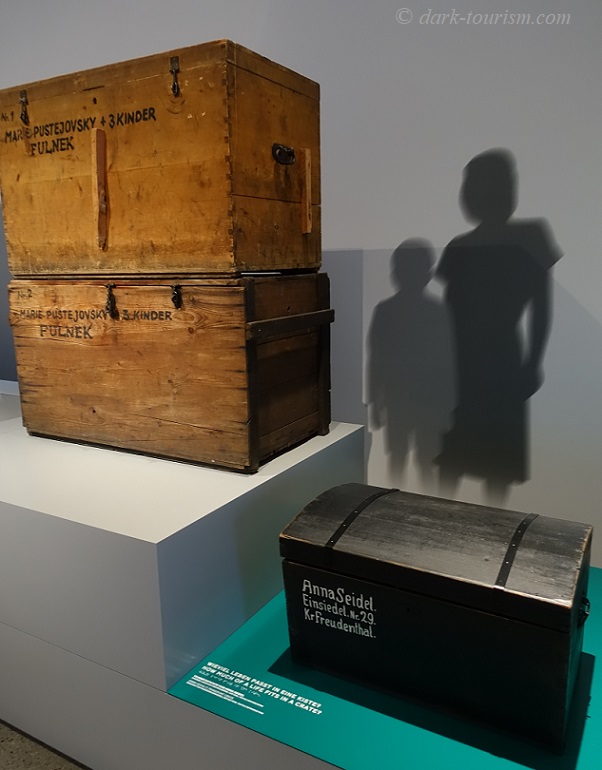

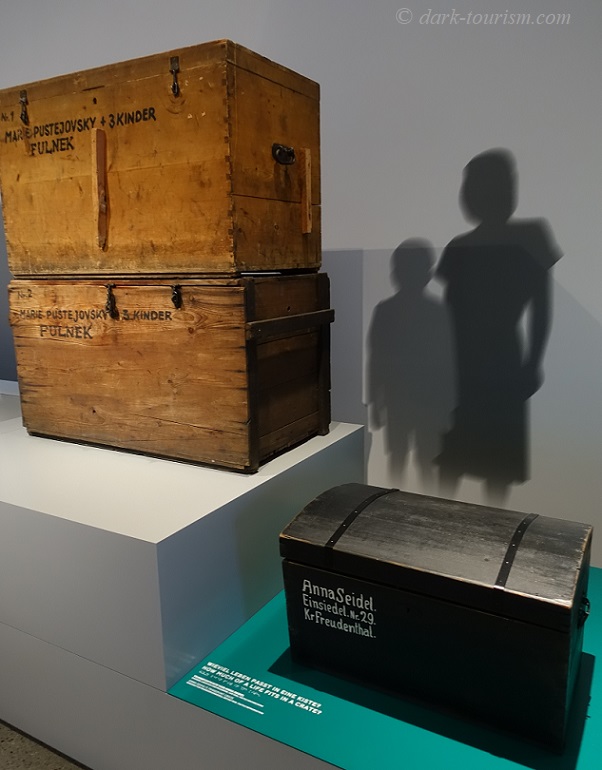

Towards the end of WWII and in its aftermath, boxes became important for the transport of personal belongings for the many displaced or expelled German civilians. This is the main topic of the new Dokumentationszentrum Flucht, Vertreibung, Versöhnung in Berlin; and that is where this photo was taken (same as the lead photo at the top of this post):

The word “box” also features in the term “black box”, denoting the fortified flight recorders that planes carry, so that after a plane crash the data can be used to reconstruct the reasons for the crash and how it unfolded. Despite the term “black box”, these devices are in actual fact usually orange, and don’t have to come in the shape of a square box, as seen in this specimen:

I spotted (and photographed) this particular “black box” amongst the jumble that was the Riga Aviation Museum, which, as I learned recently, is now closed and has been forced to move to a new location.

But to finish this post I bring you an actual black box, which also takes us back to the beginning, as it has the shape of a coffin:

This mock coffin was actually a tongue-in-cheek donations box (note the slot for coins!), which I encountered at the end of a tour of the Poison Garden in Alnwick, Northumberland, Britain.

And with this I shall come to a close. This post will now definitely be the last one of the year. But I’ll be back with more posts in the new year.

2 responses

Interesting post! Makes me wonder about the boxes I have overlooked at some sites I have visited.

Indeed. And I’m sure there would have been plenty more boxes in my archive of photos that I simply failed to think of … This kind of somewhat forced lateral thinking in themes is full of surprises 😉