For only the second time in the ca. 15 years since I started writing for my main website, I’m all caught up, i.e. I’ve completed and uploaded all the chapters that I had material for from my own travels. (The first time I had come to that point was earlier this year.)

First I finished the remaining chapters for Namibia, namely about Swakopmund and its local museum. And then I still had a substantial chapter to write about a relatively recent addition to the museum portfolio of the city I live in, Vienna, namely the House of Austrian History (“Haus der Geschichte Österreich” in the original German, or HdGÖ for short), housed in the “Neue Burg” part of the famous Hofburg complex, the former palace of the Habsburg monarchy.

In fact I bought a year ticket and went to the HdGÖ three times (it pays off if you go more than twice), once to visit the permanent exhibition, and on the other two occasions to see separate temporary exhibitions. The second one of these was about the question of what to do with Nazi-era relics people find in their attics, etc. – keep, destroy, display or give away? Indeed, quite a number of the museum’s exhibits came from such donations. And the temporary exhibition told some of the stories of how they came to the museum collection (e.g. whether anonymously or with accompanying letters with explanations).

The museum’s very biggest “exhibit” with a dark Nazi connection lies just behind a glass door by the temporary exhibition space and looks like this:

It doesn’t look like much (the wire mesh is presumably there to keep pigeons away), but this is the “Hitler balcony”. That’s the informal expression for what is in actual fact not a balcony but a terrace, or what in German architectural jargon is called an “Altan”, and it was from here that, on 15 March 1938, Adolf Hitler declared the “Anschluss” or ‘incorporation’ of his home country Austria into the territory of the Third Reich – to a cheering crowd of some 200,000. It was de facto an annexation, but one that not so few Austrians actually welcomed.

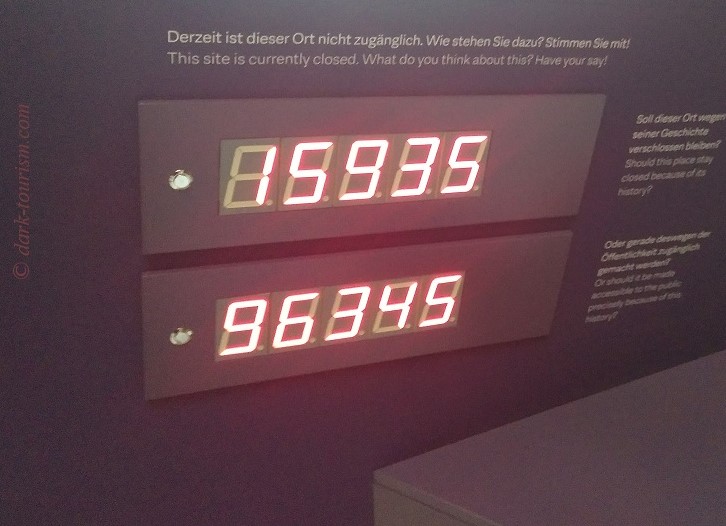

After WWII, the tarnished space of the terrace became something of a taboo. Until recently nothing acknowledged the dark historical significance of this spot, and it was just not talked about. But with the arrival of this new contemporary history museum that has changed. The balcony remains inaccessible to the general public, but the museum is running a poll as to whether to keep it that way or make the space accessible. You can cast your vote directly at the exhibit next to the door to the “balcony” by pressing one of the respective buttons. When I last visited the vote stood at this:

As you can see there’s a large majority (almost 9:1) in favour of opening the balcony up to the public. Yet so far the door to the balcony has remained locked. So sensitive is the subject.

The museum is hence also collecting suggestions regarding in what way the balcony could be “commodified” and contextualized if it were to be made accessible. You can find the collection online here (external link – opens in a new window); the texts are mostly in German only, though.

The problem here is of course that you don’t want idiots using the spot for making the Nazi salute towards the square below as a jocular pose of “re-enactment”, accompanied with insensitive selfie-taking – let alone genuine Hitler worship by neo-Nazis. The question is how to prevent this. To be honest, I wouldn’t want to be in the museum curators’ shoes on this issue …

The main permanent exhibition isn’t overly large, space-wise, but chock-full of information. And even though I have lived in this country for over 20 years I still learned aspects I had been completely unaware of. This is especially true for a little-known connection between Austria and Uganda, which explains this exhibit:

This is a Ugandan flag signed by the then president of that country. It was presented to the landlady of a village inn, where nine years previously the later president was part of a resistance group against the then dictatorship in Uganda. They met on neutral Austrian ground to discuss future forms of “just” government in that Central African country. To that end they drafted the “Unterolberndorfer Papers” (so called after the name of the village the inn was located in). They did manage to topple the regime, and the flag given as a present was to be seen as sign of gratitude. The inn’s landlady then donated the flag to this museum.

There are other exhibits that are remarkable not so much for the surprises they reveal but just for what they are. Here are a few examples:

One of the most endearing exhibits for me was this little privately made scale model of the ceremony of the signing of the 1955 State Treaty, by which Austria regained its sovereign statehood again – after seven years as part of the Third Reich followed by ten years of Allied occupation/administration:

What I found especially remarkable about this modern history museum is just how contemporary it is. The museum was opened in 2018, but seems to remain a work in progress as it goes beyond that year. Here’s an unusual exhibit related to the “Ibiza Affair” of 2019 (same photo as the featured one at the top of this post):

This USB stick contained the secretly filmed material from a meeting on the island of Ibiza of then Austrian vice-chancellor H.C. Strache from the right-wing party FPÖ with some alleged Russian oligarchs. The USB stick with the video material was then delivered to journalists who proceeded to make crucial parts public. In this meeting Strache was making promises that would have amounted to serious corruption. It was a trap, but still – thus exposed Strache was no longer tolerated by his coalition partner ÖVP under chancellor Sebastian Kurz. The coalition, and hence the government broke up and Austria was temporarily governed by independent experts until the next election was called. The “Ibiza Affair” ended the political career of Strache and ultimately also that of Kurz. The USB stick on display had to be made unreadable, hence the damage you can see, before it could be donated to the museum because it also contained other sensitive material.

The exhibition also has this not entirely serious object:

This bench with a gap enforcing distance-keeping is obviously a reference to the Covid-19 pandemic that began in early 2020 and is still not over. So it’s as contemporary as it can get.

No, wait. It did get even more contemporary: at the end of the exhibition there was a screen showing snippets of the current news of the day. It so happened that when I was there it was 8 October 2022, the day when the Kerch Strait Bridge connecting mainland Russia with Crimea was bombed and partially destroyed, so the footage of this incident in the newsreel was as fresh as it can be. Breaking news, as it were.

Not quite so current but still recent is this place name sign:

This came from a village in Upper Austria close to the border with Germany. From the beginning of 2021 it changed its name to “Fugging”. Allegedly that better reflects the local pronunciation of the name, but in reality the villagers had just got sick of the attention the old name was drawing and the tourist behaviour it triggered. The signs were also frequently stolen so they had to be replaced regularly. The new name will likely put an end to all that.

The perceived homonymy of the place name with the “F-word” in English is of course not real. And since the pronunciation is different, the first vowel being an [ʊ] in the place name, not an [ʌ] as in RP English (the phonetic notation is IPA), they are only homographs but not homophones. … but so much for this brief return to my academic background in linguistics.

As I said at the beginning of this post, I’m currently all caught up again with my main website – but not for much longer, as there are already new travel plans, in particular Cyprus in January, which will yield new material in terms of DT.

.

.

.