Twelve days ago I came back from my return trip to Iceland. Like on my first trip there back in 2004, I totally fell in love with the Icelandic scenery, be it glaciers, volcanic wastelands or dramatic sea cliffs (full of puffins in various places). Unlike in 2004, though, I brought back plenty of much better photos too, compared to the ones I took with my very first digital camera in 2004 (see this previous Blog post). So I can give you another little overview photo essay now – up to date and obviously with a focus on the dark-tourism-relevant aspects (I’d love to post photos of puffins, Arctic foxes and beluga whales too, but this is not the place for such things …).

After a couple of days in Reykjavik, Iceland’s capital and only city (a bit more on that below), I picked up a hire car and then took the ferry to Heimaey, the main island of the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago off the south coast of the mainland. This time I allowed three days for this fabulous place and I’m glad I did; I got much more under the skin of this special place than I had a chance to during my day trip (by plane) in 2004. I also had outstanding food and drink there this time. In fact, I’d love to go back already …

But now to DT. One thing I recognized from my first time on Heimaey is this bit of a former concrete water tank, semi-crushed by a lava flow, on the edge of the harbour:

This is one of the remnants of the destruction caused by an unexpected sudden eruption in January 1973. Just beyond the edge of the island’s only town, also called Heimaey, a new fissure opened up and began spewing lava and ash. Luckily, almost the entire fishing fleet had been in port, due to bad weather the previous few days, and so the ca. 5000 inhabitants of the island were evacuated by fishing boats overnight (in addition a few people were flown out). Hence there were no casualties – except one reckless man who stayed behind and succumbed to poisonous gas inhalation (the exact circumstances are a bit unclear – some say he went back to his house to salvage something, others say he broke into a chemist to steal drugs … what’s the genuine story I cannot say). The eruption carried on for six months and destroyed hundreds of homes, either directly through the lava flow or by covering them in ashfall (and I know from Montserrat how heavy volcanic ash is – it’s basically ground granite and just as heavy). Famously the lava flow that threatened to close off the harbour was stopped by spraying it with seawater (or it may have stopped regardless anyway). In the end the lava flow even improved the sheltered harbour by acting as an extra breakwater.

I also remembered a part of a house ruin poking out from under a lava flow (see this older post again). Meanwhile, I knew, a whole house ruin destroyed in 1973 has been excavated and now forms the centrepiece of a museum called Eldheimar, cleverly marketed as the “Pompeii of the North”. In addition to the excavated house that the whole museum has been built around, there’s also another, only partially excavated house ruin just outside the entrance, to provide an impression of what the excavation work must have looked like in its early stages …:

And here’s a photo of the main “exhibit” inside the museum:

You cannot enter the ruin but in addition to peeking in you can also “virtually” explore the interior by means of those interactive screens you see in the foreground here. Some household items that were found during the excavation of the site have been placed on shelves and windowsills, as you can see in this next photo:

The rest of the museum gives a vivid account of the eruption, the evacuation and the aftermath, featuring many a famous photo (I cannot reproduce them here, but you can look up quite a few of them on the museum’s website – external link, opens in a new tab). In addition to the coverage of the 1973 Eldfell eruption, there was also a separate section when I was there that was about the creation of the new island of Surtsey by an undersea volcano in the 1960s.

One place that was also covered by ash in 1973 was the town’s cemetery. And here the post-eruption excavation had to be carried out by hand and shovel, as no heavy machinery could be used for fear of destroying the graves beneath the ash layer. The arch over the entrance was the only thing that poked out of the sea of black ash back then. Today the restored cemetery and its entrance arch look pristine:

But look on the right – there’s a black column and a plaque, seen here closer up:

The panel shows one of the famous photos taken during the 1973 eruption at this very location; and the black column next to it indicates how deep the ash was back then. Such markers can be found all over the town these days.

Impossible to overlook is the 1973 crater itself, which was rather unimaginatively named “Eldfell” (meaning ‘fire mountain’). This is what the red tephra cone looks like today (seen from the cemetery):

While Eldfell and the story of its 1973 eruption are a dominant feature on Heimaey (another example of dark tourism being in the mainstream for once – cf. also this earlier post), there are other darkish aspects too. For one thing there are the warning signs telling people to stay clear of the many steep cliffs’ edges (which are indeed very tempting to get close to in order to watch the endearing puffins!). As if to provide additional evidence for this, there was part of a tractor wreck clinging precariously to the very edge of one of those cliffs:

And as you would almost expect of an island, there were also shipwrecks. A couple have their own memorial monuments and a recent large monument in the harbour commemorates all the fishermen from Heimaey who lost their lives in the course of doing their job over the decades. But I also found remnants of shipwrecks without any commodification … just lying there:

Other than on Heimaey, volcanism also plays a major role in many parts of Iceland. They say that, on average, the nation experiences a volcanic eruption every four or five years. But in recent times this rate has been much higher. The volcanoes of the Reykjanes peninsula, which lies just south of Reykjavik, and is home to its international airport at Keflavik, had been dormant for several hundreds of years until in March 2021 a new eruption at Fagradalsfjall began. This lasted until September. The following year another eruption started nearby in August 2022 (and ceased after just a few weeks). And then on 10 July 2023 yet another eruption began further inland at Litli-Hrutur. All three became instant tourist attractions (including a large part of domestic tourism!). The type of these eruptions makes it quite safe to observe from comparatively close up. Hence they are locally sometimes dubbed “tourist volcanoes”.

When I travelled to Iceland at the end of July, the eruption was still going strong. So I had booked a helicopter flight over Litli-Hrutur (at quite some cost), also because I knew I wouldn’t have the time for the considerable hike it takes to reach the site on foot (in total ca. 6 hours, partly through some demanding terrain). But I really wanted to see a lava-spewing volcano in action with my own eyes (other eruptions I’ve seen on Montserrat and Hawaii were of different types). Unfortunately, on the day I had booked the flight originally, 30 July, low clouds meant no visibility. We waited for about two hours for the cloud cover to lift, but it didn’t, it only got worse. And so the flight had to be rescheduled. Fortunately we would be close enough to Reykjavik again on 5 August so we rescheduled for that day.

But bad luck struck twice. 5 August was also the day when the eruption ceased. At least I had a forewarning this might happen from the guide at the Lava Show in Vik the day before (see below). We still went on the helicopter flight, however, and even though there was no more spouting lava fountains and red-hot lava flows, it was still a very cool thing to do. Here’s a photo taken from directly above the Litli-Hrutur crater – you can still make out some orange lava glow inside and on the left edge:

On a nearby hill I saw several hikers who had made their way to the volcano the hard way, only to be disappointed even more (from the side you couldn’t see any orange glow at all any more, just the residue smoke coming from the crater):

Other than this little glimpse of lava inside Litli-Hrutur and all those still smouldering black lava fields around it, my only close encounter with lava was at the aforementioned Lava Show in Vik, a small town on the south coast of Iceland. Here they take some black sand from the nearby beach, which basically consists of ground-up old lava, and re-melt it in a backstage furnace to recreate genuine lava. You have to wear glasses for protection against the intense heat as they release the liquid lava down a specially constructed chute. As the lava begins to solidify, the guide demonstrates its malleability by lifting a section up in the middle of the flow by means of a steel stick, which he also uses to poke about the end of the lava flow, as seen in the next photo:

The Lava Show also has a branch in Reykjavik, but the one in Vik was more convenient for me, being close to the Ring Road along the south coast, whereas in Reykjavik I was more pressed for time (partly because of that helicopter flight that then didn’t happen).

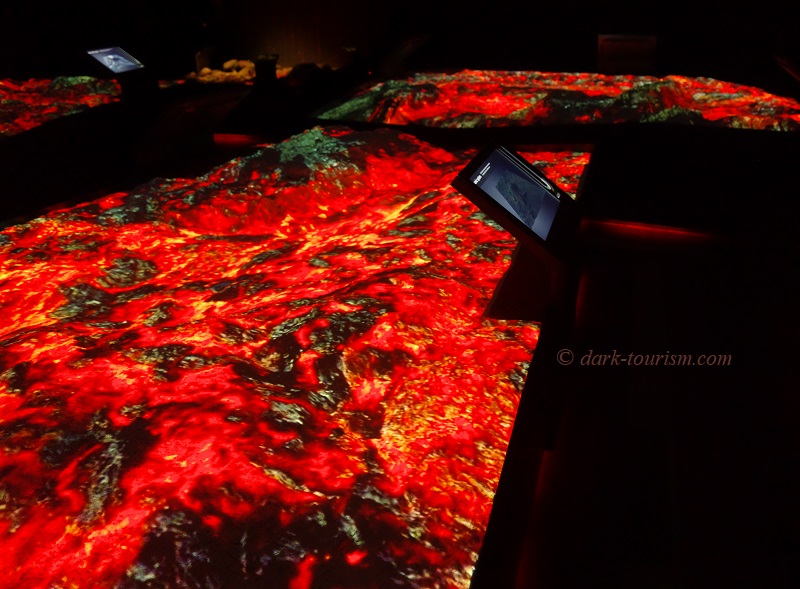

Also just by the southern Ring Road is another volcano-related attraction that opened only a few years ago, the “LAVA Centre” in Hvolsvöllur. The main exhibition is highly interactive and covers the entire volcanic history of Iceland, including its most catastrophic events (such as the Laki Fires of 1783/84, which killed off half the Icelandic population and caused crop failures all around the northern hemisphere). You can physically experience different types of earthquakes and of course there’s also plenty of vulcanology explained. In that section there is also a clever light installation emulating a lava flow, as seen in this picture:

Volcanism on Iceland creates not only lava and ash (the latter affected much of Europe’s airspace during the Eyjafjallajökull eruption of 2010), it can also release flash floods! The technical term for these is ‘jökulhlaup’, an Icelandic word that’s been adopted into international science speak. It refers to events caused by subglacial volcanic eruptions, as take place with some regularity in Iceland, especially at the Grimsvötn system underneath the Vatnajökull ice cap (the largest in Europe, and second largest in the northern hemisphere after Greenland). When a volcanic eruption hits glacier ice it melts huge amounts of water and this often finds its way out in violent bursts, also carrying along broken-off icebergs the size of houses, that destroy everything in their path. Hence the vital Ring Road along the south coast had to be reconstructed several times over following jökulhlaups. There’s a monument by the roadside that consists basically of two twisted steel girders of a bridge that was otherwise totally destroyed in such an event:

Even without the “help” of volcanic eruptions, water can have its own destructive forces, some of which lead to shipwrecks. An example can be found near the fishing harbour town of Grindavik on the south coast of the Reykjanes peninsula, as seen in the next photo:

Not only ships can become wrecked, planes too. The most famous is probably the US Navy DC-3 plane wreck that for 50 years has been sitting at a lonely spot on one of the vast black sand beaches of the south coast of Iceland, namely on Sólheimasandur (you may have seen it on Atlas Obscura – external link, opens in a new tab). As you can’t drive up to the wreck and the hike through nothing but endless black sand is said to take 3 to 4 hours I gave it a miss on my recent trip. I’ve only since learned that some enterprising Icelanders now run tours by special high-clearance buses to the site … but then again, I don’t think the atmosphere could be enhanced by a large group of tourists. Maybe on my next visit to Iceland I’ll factor in time for the hike … I did, however, on this occasion make a short stop at a recent monument to another US plane crash, a B-24, as seen in the next photo:

Two panels by the monument also point out a number of other plane crash sites around Iceland, including, to my surprise, one by a German Nazi Luftwaffe Ju-88 in 1943. I wasn’t aware that the Nazis had managed to get to Iceland by air during WWII …

Perhaps not dark tourism in the most classic sense (though there are also some dark legends about it), but still quite off the usual tourism tracks, and featuring unparalleled barrenness and desolation, is the uninhabited interior of Iceland. For me this is one of the key attractions of the country. Just driving for hours in the vast emptiness that looks like the surface of the Moon in many places, feels wildly adventurous … though on the Kjölur Route (F-35) that I took, it is actually quite safe and easy provided you drive a sturdy 4×4 vehicle (normal cars are not allowed by car rental companies to be taken on such routes). Just look at this level of desolation:

At one point I managed to take a “wrong” turn – which is quite a feat, given that there are only a couple of turn-offs along the ca. 100 miles of gravel track. But that way I came to an area by chance that I would otherwise have passed by. Luckily I didn’t. The highlight here is a colourful geothermal area at Kerlingarfjöll, with lots of steaming vents dotting the hillsides. And there was still plenty of snow, even in early August (same photo as the featured one at the top of this post):

While Kerlingarfjöll is one of the spots in Iceland that give justification to its epithet “land of ice and fire”, another natural phenomenon is more watery, but still the result of geothermal activity: the Geysirs. These are of course world-famous and as they are easy to reach, they’re very popular with tourists (the main area is right on the famous “Golden Circle”). The Geysir of that very name, which lends its name to the phenomenon at large, is these days mostly dormant (though I was lucky enough to see it spouting once when I was first there in 2004). But its neighbour, called Strokkur, is one of the most regularly active geysirs in the world. It erupts every 8 to 10 minutes and reaches heights of up to 35m (115 feet):

What I found most attractive about this geysir is actually the build-up, when a big blue bubble forms and then bursts, releasing its steam and boiling water, as captured in this series of photos:

So much for natural phenomena and scenery. As I said I also spent a couple of days in Reykjavik. When I was there in 2004 there was a volcano film show, mostly about Heimaey 1973 (see above), but this no longer seems to exist. However, there’s a branch of the Lava Show in the harbour (see above about the branch in Vik). And I also spotted the odd little darkish detail. One is the curious monument donated by Latvia in gratitude for Iceland having been one of the first nations to officially recognize the Baltic States’ declarations of independence from the then Soviet Union, even before the latter itself collapsed.

The monument is located on a square whose name these days also has a dark ring to it: Kyiv Square.

In fact the square was renamed (it was previously called “Reykjavik Plaza”) in solidarity with Ukraine because of the war that Putin’s Russia has subjected it to since February 2022. So there is a very current, very dark link here. “Kænugarður”, by the way, is an old Icelandic name for the Ukrainian capital (apparently there is a history of Scandinavian settlers in the territory of today’s Ukraine behind this – see here; external link, opens in a new tab).

Finally, some people also see a bit of dark tourism in the history of the Vikings, which obviously also has strong links with Iceland. For me that’s actually too old history to be relevant to dark tourism proper normally (as I follow the Lennon/Foley school of thought that situates dark tourism in the modern era), but here I’ll make allowances. One expression of the Viking link is a large steel monument by the waterfront in Reykjavik. It’s supposed to be an abstract representation of a Viking longboat … though to some it looks more like some strange crustacean that’s crawled on to land.

And with that I shall come to a close … Unmentioned in this post, however, is one more very special dark attraction. I deliberately left it out here as I intend to give it its own stand-alone blog post before long. It really was that special. Just wait and see …

2 responses

Fantastic read and great photos, very informative. We travel to Iceland for four nights in November. Only a taster visit and hopefully a prelude to a longer visit in the future.

thanks! Iceland in November will be very different – short daylight hours, lots of places will be closed off season, and snow may restrict getting around. BUT: there will be far fewer other tourists, AND you may get the chance to see the Northern Lights!