On this day, 75 years ago, on 16 July 1945, the first atomic bomb explosion was set off in what was called the “Trinity” test in the desert near Alamogordo, New Mexico, USA. The image above is a historic photo of the mushroom cloud that formed shortly after the detonation. The whole event was meticulously documented, including by means of super-high-speed cameras. Here’s another example; it shows the fireball beginning to rise an instant after the device was triggered:

Both of these historical photos, by the way, are in the public domain (and gleaned from Wikimedia).

The device, nicknamed “The Gadget”, and its successful testing were the culmination of the Manhattan Project. Its design was largely the same as that of the “Fat Man” bomb that was later dropped on Nagasaki. The simpler gun-type design on a uranium base for the Hiroshima bomb was used untested. But “The Gadget” and “Fat Man” were plutonium implosion bombs, a much more complex design, whereby a mantle of conventional explosives is set off simultaneously to compress a plutonium sphere in the core into a critical mass thus triggering the nuclear fission chain reaction that such a detonation is. Following the success of the test, the technology became the blueprint for the majority of the nuclear arsenals stockpiled in the early phases of the Cold War (until thermonuclear devices arrived).

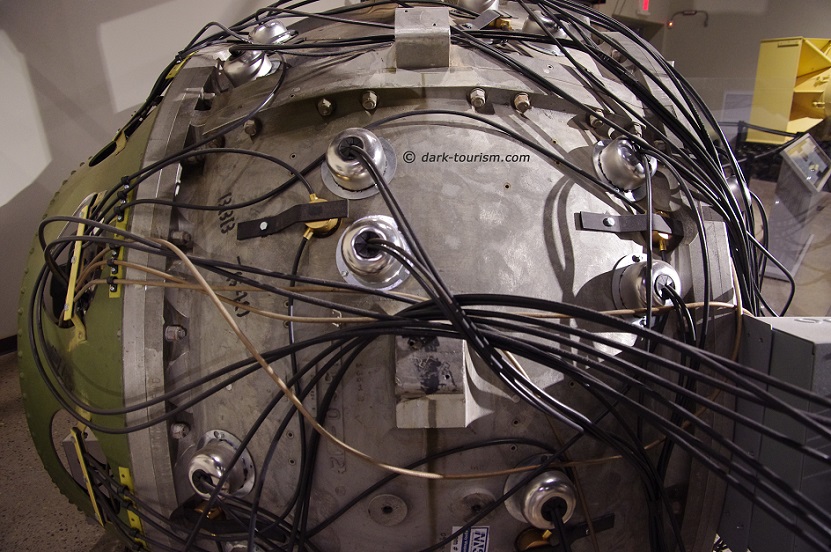

In the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History in Albuquerque a model of “The Gadget” is on display:

The site where the Trinity test took place lies within a restricted military area, namely the White Sands Missile Range, and is thus normally off limits to ordinary people. But on two days each year the site can be visited by the public (for a while this was reduced to just once a year, but meanwhile the twice-yearly schedule has resumed) – these open days are usually on the first Saturdays of April and October. On these “Trinity Days” you can drive your own vehicle either in a convoy from Alamogordo, or individually from the north gate, but are under strict instructions to stay on the prescribed route. At the car park by the fenced-off Trinity site an almost festive atmosphere develops on those open days, with BBQ stalls and drinks sellers. But the presence of uniformed soldiers acting as guards serves as a reminder that you’re still in a special place. The radioactivity signs on the outer fence of the Trinity site also point out that this is no normal locale.

However, ambient radiation is really no worry here, residual radiation is maximally about ten times higher than usual natural background radiation, but if you stay here for just an hour or so you get only less than half the dose extra that you would receive elsewhere in a day anyway. X-Rays and CT scans expose you to more.

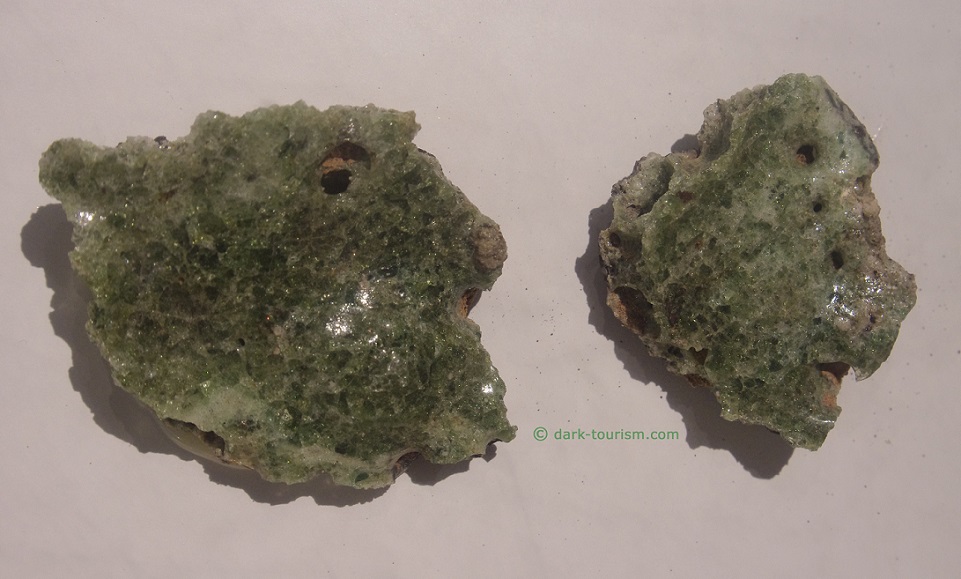

And even the radioactive materials in the ground are no longer so dangerous. The main material in question is so-called ‘trinitite‘, a greenish, glass-like substance that formed when the heat of the fireball of the explosion melted the desert sand and fused it into this new kind of material. You can still find some of it in the inner area, a roughly circular space with a second fence around it. By the gate is another warning sign pointing out that you are not supposed to take any pieces of trinitite with you.

Despite the warning, for many people the first thing they do when they get there is try and find some trinitite. I was no exception when I visited the place in April 2012 …

In fact it did not take long to find some trinitite. These pieces I found were a bit dusty, but at the National Nuclear Museum in Albuquerque they also have on display some cleaned pieces of trinitite in all their green glory:

Within the ground zero site of Trinity one patch of the original layer of trinitite is protected by a special roof, but the hatch that would allow a peek in was unfortunately closed when I was there.

Also within the ground zero area is a trailer with a mock-up of the Fat Man bomb casing like the one dropped on Nagasaki on 9 August 1945.

The centrepiece, literally, of the site is the stone marker at the very spot of the explosion, This steep-pyramid-shaped monument was erected in 1965.

The tower that “The Gadget” had been suspended from was almost totally vaporized by the heat of the detonation, but you can still see a little stump of concrete with a couple of cut-off steel spikes, which was once one of the tower’s bases.

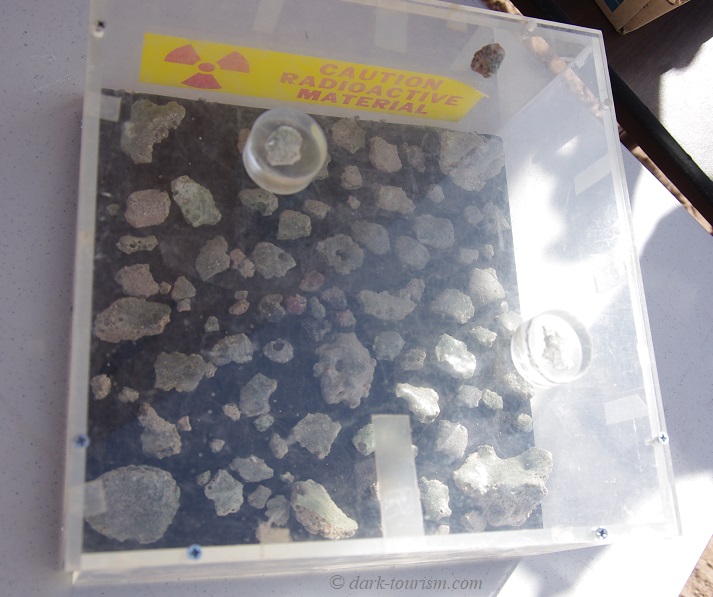

Back at the car park you can take a look at yet more trinitite in display boxes – and even though you’re not allowed to take any pieces you can collect from the ground yourself out with you, it is possible to purchase pieces! I wonder how those online trinitite vendors got hold of their wares in the first place …

Actually, in the early days people just went in – see esp. here! – and carted the substance away, until in the early 1950s it was made illegal and the site was bulldozed over except for that one protected patch; but samples that had already been taken away could be sold legally and are still in circulation, and in plentiful supply! How much of the stuff offered on the Internet is genuine, is another question – though with the right equipment and know-how, samples can be tested for authenticity (see this rather technical account).

On the twice-annually open days the military also offers a (free) shuttle bus ride to McDonald Ranch House several times throughout the day This was the building the military had taken over from its owner in 1942 specifically to later serve as the place where the final assembly of “The Gadget” was to be undertaken.

Inside is a small exhibition and one room is marked “plutonium assembly room”. That’s a bit shorthand though, as it wasn’t plutonium as such that was “assembled” here (that had been made at Hanford). Instead it was the plutonium core that saw its final assembly here, namely from two hemispheres put together with the polonium-beryllium initiator in the middle, and together this formed the so-called “pit” of the bomb (I’ll spare you the nuclear physics details – if you’re interested look them up yourselves … I always find them fascinating, but I’m aware not everybody is so inclined).

Taking part in this Trinity Day in April 2012 was definitely one of the highlights of my trip to the American West back then (it covered parts of Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and Nevada). There isn’t an awful lot to see, but the significance of the history-changing event that took place here hangs heavy over the site, despite the many people and the convivial atmosphere.

Trinity was in fact my second historical “ground zero” that I visited – remember the blog post from 10 June about the Semipalatinsk Test Site, aka the Polygon, in eastern Kazakhstan! That is the place where the Soviet Union conducted its first nuclear test in 1949 – and several more in the years after that, whereas the Trinity site was used only the once. Subsequent nuclear tests by the USA were mostly conducted at the Nevada Test Site or on Pacific islands like Bikini.