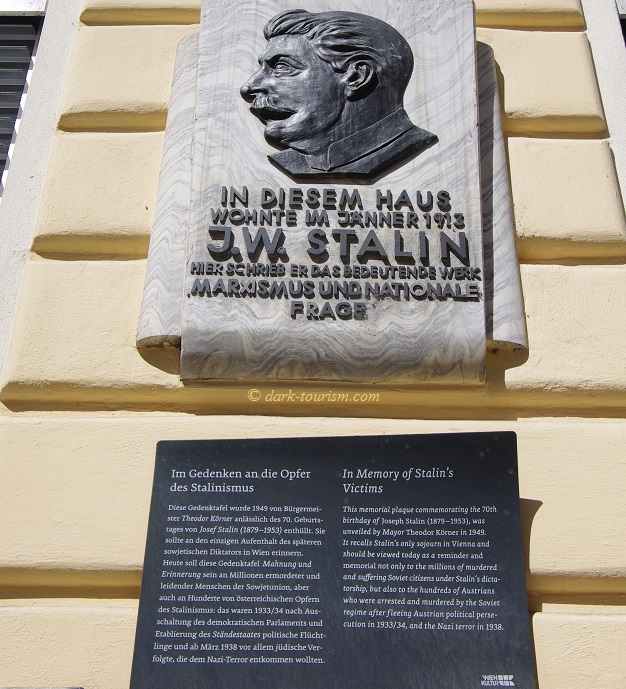

The photo above shows a plaque in Vienna commemorating Joseph Stalin’s short sojourn in this city as a young man. I’ve been reminded of this by the recent images on the news from the USA, where protesters are disfiguring or toppling monuments to former proponents of slavery and such like, in the wake of the unrest caused by the killing of George Floyd by police. Now, how do the topics of Stalinism and the Black Lives Matter movement go together, you may ask. Let me explain:

Make no mistake, I do understand the outrage of the protesters about the celebration through grand monuments of people who, at least by today’s standards, have to be regarded as racists and human rights violators, like those Confederates involved in slavery back in the day. It’s perfectly understandable that contemporary African Americans take issue with such things. But I’m asking myself: is iconoclasm, the destruction of such old monuments, really the answer?

This is where this example from Vienna comes in. The plaque with Stalin’s portrait was put up in 1949 (on the occasion of Stalin’s 70th birthday), at a time when Vienna, like all of Austria, was still under Allied occupation, which followed WWII. It was clearly something that the Soviets wanted marked: namely the fact that young Joseph Stalin stayed in this house in January 1913 and wrote a certain socialist pamphlet about ‘Marxism and the National Question’ that was published a few months afterwards and apparently made quite an impact within Bolshevik circles.

When Austria was finally released into independent statehood again in 1955, this was under certain conditions. Military neutrality was the key one, but there were also other aspects, including the obligation of the Austrian state to preserve Soviet monuments left in the city. Amongst those is first and foremost the grand victory memorial complex at Schwarzenbergplatz (referred to by some, in black-humoured Viennese fashion, as the “monument to the unknown rapist”). But there’s also this comparatively small plaque on a house on Schönbrunner Straße 30.

In more modern times, the Stalin plaque was seen as a bit of an embarrassment, and some people would have liked to see it removed. But even after de-Stalinization in the USSR itself, let alone after the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War, the obligation to preserve such monuments still holds. So instead of taking it down, a second plaque was added underneath. And this features additional text that puts things into perspective, and points out the commemoration of Stalin’s victims, both in the USSR itself but also those Austrians who became victims of Stalin’s reign of terror after they’d fled persecution in Austria in 1933/34, and especially after the Anschluss (annexation) by the Third Reich in 1938.

This is the alternative approach to iconoclasm, and I for one think it works better. The old monument is retained, rather than erased from memory, but commented on from a contemporary vantage point to properly put it into perspective. Maybe this could be something to be also considered for those monuments in the USA that are currently the targets of wild vandalism. (Btw., there are hundreds of historic sites and monuments in America that could do with a better interpretation, as laid out in minutiae in the nearly 500-page tome “Lies Across America – What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong” by James W. Loewen, New York, London: The New Press, 1999/2019.)

Yet another approach of dealing with monuments that are no longer wanted or deemed appropriate is that followed e.g. by the ‘Memento Park’ of socialist statues and other artwork on the outskirts of Budapest, Hungary, or the MUZEON Park of Arts in Gorky Park, Moscow, Russia, which also features a collection of statuary and monuments from the old Soviet days (and is also known as “Park of Fallen Heroes”), including plenty of Lenins, Marxes, Brezhnevs, and even a couple of Stalins (one with his nose hacked off).

Other former Eastern Bloc countries have similar sites (e.g. Tallinn, Estonia, or Sofia, Bulgaria). In all these locations it’s the amassed presence and random arrangement of the statuary that takes the former glory out of these redundant pieces of propagandistic art. That and, again, extra plaques that add a bit of context. In the most (in)famous such sites, Grutas Park in Lithuania, there are even full museum exhibitions to further commodify the relics. The fact that the park also includes a grand statue of Stalin, is probably the reason why the site is informally known as “Stalin World”.

Yet another way of dealing with statues and other monuments no longer wanted out in the open, other than simply destroying them, is to take them away and put them inside museums, again with proper interpretation for context. That way, even a golden Adolf Hitler bust can be OK to display, as in the Military History Museum in Vienna. And with that we have come full circle again.

The latter, obviously, also reminds me of my first post here, about that toppled Hitler bust and smashed in portrait at the Mémorial de Caen. It’s precisely this contexualization, which makes such displays OK, that the daft Facebook algorithms are incapable of understanding.

One Response

the wave of iconoclasm in the wake of the George Floyd murder/Black Lives Matter protest also reached Europe, not least the UK, but also for instance Belgium, where the commemoration of the legacy of King Léopold II is being challenged. This king was possibly the most ruthless colonialist ever, running the Congo as his personal private fiefdom to exploit, and his henchmen meted out the harshest of punishments (e.g. the “tradition” of hacking off limbs in this part of Africa began with the Belgians!); as many as 10 million Congolese lost their lives there during Léopold’s colonial period between 1885 and 1909 (which inspired Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”, by the way). Yet even in Belgium there are voices calling for additional plaques for putting things into context rather than simply the removal of all the statues of and monuments to the king. See this recent article: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/12/belgium-forced-to-reckon-with-leopolds-legacy-and-its-colonial-past