First of all, I can’t claim credit for the featured photo above, because I didn’t take it, my wife did (she’s developed quite an eye for such compositions!), namely when we were last in Russia. This photo was taken in St Petersburg and shows a reflection of one of the most iconic sights in this city, namely the Church of the Saviour on Spilled Blood … what a name in the current circumstances! (But its name is actually a reference to the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881.)

Secondly, I know in the West all eyes are currently on Ukraine and especially the Ukrainians, who are suffering the most in this ongoing war, and I naturally feel for them too. But my heart also bleeds for Russia – for various reasons I will try to explain in this post. This is partly inspired by stories I read about animosity towards ethnic Russians in various countries, including my original “home country” Germany.

But one has to remember that Russia is not Putin and Putin is not Russia. He may (still) enjoy much support especially amongst those Russians who follow only the state-run TV reporting and who lap up all the disinformation at face value, after years of constant uniform pro-Putin propaganda that is now the default … Never underestimate the power of “Gleichschaltung” (external link, opens in a new tab)!

(As my British guide in North Korea once said, when asked how come the North Koreans believe all that official narrative that we outsiders find so crazy: “if all you ever hear and read is all saying the same, then for you that is the truth …”.)

But there are also other Russians, especially among the younger generations, who get their information from international sources as well and can see the discrepancies between the different narratives. This is driving a massive wedge between sections of Russian society at the moment. Just like Brexit did in the UK, this divide is ripping right through families, with Putin-devoted parents calling their offspring “traitors” for not believing the official propaganda and calling anything that deviates from the official line foreign “fake news”. The more enlightened, more internationally minded, mostly (but far from exclusively!) younger parts of society are now suffering from a broken world turned upside down. Needless to say, this is also severing lots of the many Ukrainian-Russian family ties (see e.g. here – external link, opens in a new tab). I also know ex-pat Russians who can no longer speak to their families back in Russia. The divide is too big. There’s no getting through to them.

Naturally, I also feel for all the tour guides I had in Russia, all with excellent English, whose services were aimed specifically at Western tourists, who are now no longer coming, so they now will presumably have lost their jobs in the tourism industry for the foreseeable future, if not for good.

I’ve been to Russia four times. The first visit was way back, when Russia was still part of the Soviet Union. It was a short organized group trip in February 1987, so in winter, to Leningrad (St Petersburg’s name in the Soviet era). This was in the early days of Mikhail Gorbachev’s Glasnost and Perestroika, and our tour guide, when pressed, very cautiously indicated signs of hope for a better future. Yet I also vividly remember those depressing shop windows with nothing but stacks of uniformly labelled tins of unidentifiable food, the lack of advertising other than Communist Party slogans, and the general greyness and oppressiveness …

My second trip was in the late (pre-Putin) 1990s with my girlfriend (now wife) who had lived, studied and worked in Russia for a year and a half in total and had personal contacts in the country, who we also visited. That brought me many insights into how much Russia had changed through the post-Soviet 1990s. Yet there were still plenty of remnants of Soviet-like aspects and drabness left, despite the odd Western fast-food chain branches and adverts to be spotted in Moscow and Yaroslavl and more Western wares available in the shops.

My third trip to Russia was only a two-day excursion in 2012 to Murmansk from Kirkenes, across the border in Norway (rather extravagant going through the lengthy and costly visa application process for just such a short period of time!). So that doesn’t really count.

But it was my almost four-weeks-long extensive trip to Russia in August 2017 that gave me the most recent in-depth impressions of (then) contemporary Russia. What a far cry it was from my 1980s and 1990s impressions! I found a vibrant, youthful, open-minded culture, at least in the big cities. I saw more hipsters in Moscow than I have ever seen in Berlin, London or Paris, tattoos on younger people seemed to be omnipresent, there was a flourishing craft-beer scene and the culinary experiences to be had in general were outstanding – and international.

The following photos were all taken on that trip and present impressions from a Russia distinct from the usual postcardy images from Red Square, Tsarist-era palaces or other clichéd and familiar visual icons.

The first photo, however, does include one of those icons, namely the Hermitage in St Petersburg (the former winter palace and now one of the world’s leading art museums), BUT: seen from the Kunstkamera across the river and taken through some big glass lens so that it appears upside down … Again, this suddenly takes on a new symbolism given recent events:

.

.

Further up the river there’s a memorial complex to the victims of political repression – which now also feels different, almost cynical, given the renewed and intensified repression of dissent in Russia today. What with mass arrests of protesters and a new media law that essentially criminalizes truth itself and makes the current official propaganda Newspeak mandatory for all. Hence this image also takes on some extra symbolism:

.

.

The actual main part of the monument is this, though:

.

.

The red-brick complex seen in the background on the other bank of the river, by the way, is Kresty prison – and you have to wonder whether this would have held any of those detained anti-war protesters … However, this old prison was apparently closed a few years ago.

St Petersburg, then called Leningrad, was a tragic war victim in WWII, namely when the city was under siege by Nazi Germany for nearly 900 days. The Wehrmacht shied away from capturing the city militarily and instead surrounded it, kept on shelling it and cut off most supplies. Up to a million civilians died of hunger and the cold in Leningrad. There’s a grand monument south of the city centre of St Petersburg commemorating the siege and the defenders of the city. It includes this sculpture of an exhausted and frightened looking female civilian, who almost appears to be bathed in sweat (thanks to a heavy downpour shortly before I took the photo):

.

.

It is beyond ironic that now Russia is using similar siege and shelling tactics against Ukrainian cities …

One of the burial sites for the victims of the Leningrad siege was Serafimovskoye Cemetery on the north-western outskirts of the city, which is also of interest to dark tourists as it’s there that most of the victims of the Kursk submarine disaster are buried. Otherwise it’s just a very atmospheric cemetery. One of the tombs I photographed there I can now also see as re-interpretable symbolically. A young woman in a “cage”:

.

.

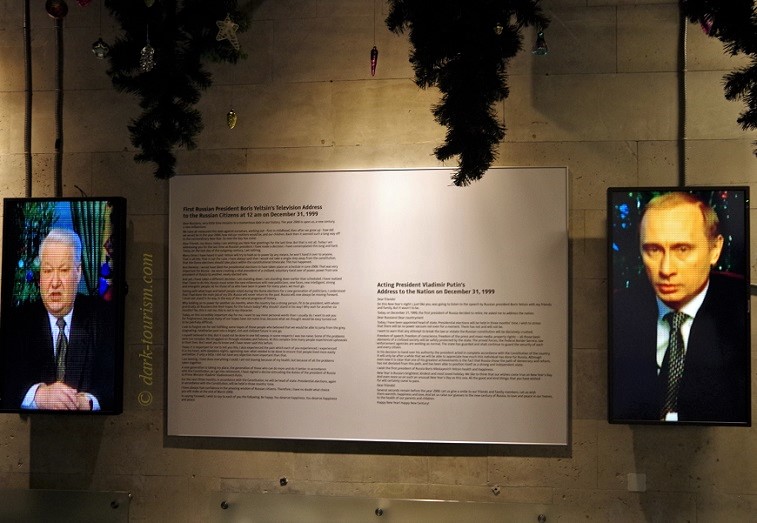

St Petersburg also has a “Museum of Political History” – formerly the “Museum of the Revolution” in Soviet times. This was substantially overhauled and enlarged after the collapse of the USSR, also to cover some of the various dark sides of Soviet history, from political repression to the Soviet war in Afghanistan. Coverage goes beyond the Soviet era and into modern Russia, but when I saw it in 2017 the exhibition’s coverage stopped at around the beginning of the Putin era, with the addresses made by Yeltsin and Putin on 31 December 1999 after the handover of power:

A famous figure of pop culture born in Leningrad was the legendary Viktor Tsoi of the band Kino. Tsoi died in a car crash in 1990, so didn’t live to see the end of the USSR. I wonder what he’d have to say about current developments. Anyway, he’s still a revered rock legend all across the former Soviet Union, where you can find his portrait in graffiti form in many places far and wide. In St Petersburg, there’s a large mural of Tsoi right on the wall of the rock club where he started his musical career:

Here’s one final photo from St Petersburg, of a lavishly decorated gourmet food and drinks shop on the city’s main boulevard Nevsky Prospect:

After overcoming the economic turmoil of the immediate post-Soviet era, Russia saw some significant growth in wealth – not for everybody, mind; poverty was and still is widespread – but for a well-off section of society, luxuries from all over the world became available … and “flauntable”. The current sanctions on Russia will have put a massive dampener on this now. In this photo you may be able to spot a few familiar Western brands that may not be so easily available any more before long. As for cheese, there had already been an import ban, or at least restrictions on Western cheese imports, since 2014 (in response to Western sanctions after the annexation of Crimea). And so local craft cheesemakers tried to fill the gap by imitations – to varying degrees of success. Some I sampled in a regional food restaurant in Moscow did impress. But I wonder what the outlook is for shops like this one in St Petersburg in the coming economic difficulties …

Apart from St Petersburg, I also visited the capital (see below) as well as a few other cities on my 2017 trip to Russia, including Perm in the Urals (as a base for a day trip to the Perm-36 gulag memorial), Yaroslavl north of Moscow and Volgograd in southern Russia. The latter is the former Stalingrad, and the Battle of Stalingrad, the big turning point in WWII when Nazi Germany suffered its first major defeat, is highly commodified in today’s Volgograd. Amongst its war-related sights is this war ruin, the former Grudinin Mill, which was left in its shelled and hollowed-out state to serve as part of a larger memorial complex:

You have to wonder whether any such war ruins currently being created in Ukraine will one day also serve as a memorial …

Part of my 2017 summer trip was also a couple of days in rural Russia, in “dacha land” (‘dacha’ is the Russian word for a summer house with a vegetable garden in the countryside), to stay with contacts my wife still had there from her student days. And there I spotted this sign of Russian patriotism – a Russian flag, complete with coat of arms, made from coloured plastic bottle tops(!):

However, the longest stretch of time in my 2017 Russia trip I spent in the capital Moscow, because it is such a treasure trove for dark tourism. While I found familiar sights such as the Kremlin and Red Square largely unchanged, the cityscape had been transformed substantially in other respects, most strikingly in this modern business district which is now home to some of the tallest buildings in Europe:

On my dark-tourism itinerary in Moscow were a wide range of attractions, some long established and going back to Soviet times, others newer and more modern, such as the unique Gulag History Museum with its intriguingly designed exhibition:

Another newer addition to Moscow’s dark-tourism portfolio is the excellent Jewish Museum & Tolerance Center, which I found to be one of the best museums of its kind worldwide, especially for its extensive coverage of both the Holocaust, perpetrated by the German Nazis within the USSR during WWII, and the subsequent repression and persecution of Jews within the post-war Soviet Union/Russia. The exhibition’s design with super high-tech installations, plenty of projections and interactive elements was apparently financed with the help of some super-rich Jewish Russian oligarchs abroad. Here is just one impression:

.

.

Amongst the older dark attractions is Stalin’s bunker, which he had built at the beginning of WWII as an emergency relocation centre under a sports stadium in a suburb of Moscow. This site had long been a secret and was opened to the public only in the 1990s, but remains difficult to visit (by specially arranged guided tour only). In the central hall there is this meeting room with a big round table … from a time when such tables were circular rather than ridiculously long:

.

.

And at Moscow’s Museum of Contemporary History I spotted this image, which suddenly has become a lot more poignant than it would have been when it was made:

.

.

The word formed by the leaves of this tree,“славянство”, means something like “Slavdom”, a reference to the “brother” peoples that Russia and Ukraine considered themselves to be. That closeness has now been completely poisoned by the war. Whether it can ever be restored remains to be seen. Right now it seems unlikely.

One evening after walking along the Moskva River opposite the Kremlin, we then took the bridge heading back to Red Square – and that’s when we passed the grass-roots memorial at the spot where Boris Nemtsov was gunned down in 2015:

.

.

Nemtsov was possibly the last credible opposition leader who could have made a suitable successor to Putin and his increasingly repressive regime and could have saved Russian democracy. In the end that’s speculation, of course, but it was undeniably one of the biggest blows to dissent and freedom within Russia in the last decade. It’s remarkable, though, that this memorial is still there. It featured in recent footage of anti-war protests by a brave few who assembled at this very spot!

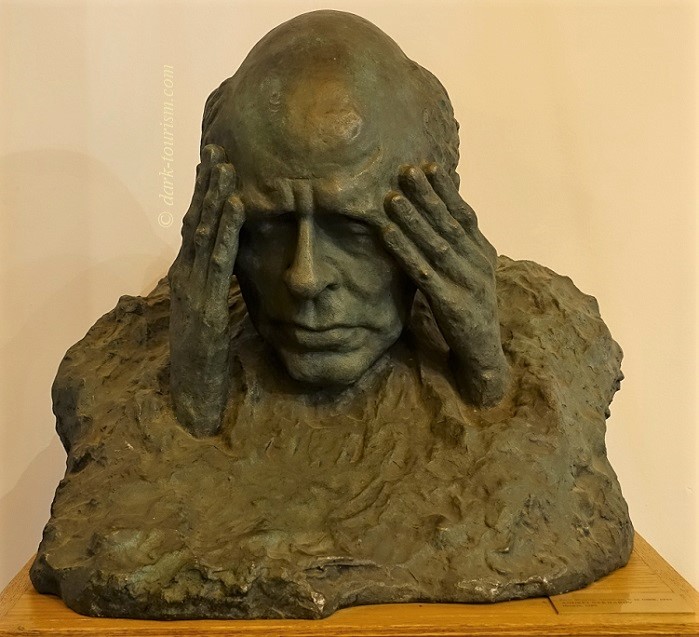

Another dissident, but one from the olden Soviet days, was Andrey Sakharov, a nuclear scientist who later spoke out against the nuclear arms race and against repression and human rights violations in the USSR. Sakharov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975 (but was not allowed to travel to Oslo to receive it) and was exiled to Gorky from 1980. He was freed under Gorbachev in 1986 but didn’t live to see the end of communism, as he died in 1989. But his name and legacy live on, for instance in the form of the Sakharov Center NGO which opened a small exhibition in Moscow. The exhibition includes a bust of Sakharov, pictured below:

.

.

Again, you can now see a new symbolism in this bust and Sakharov’s pose … as if he’d had a premonition of today’s developments … And you have to wonder what future, if any, the Sakharov Center may have now, given the ever tighter iron-fist rule of Putin, especially when it comes to NGOs.

And talking of reinterpreting sculptures (which I like to do especially at cemeteries – see e.g. here!), this pair, spotted at Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, can also be seen in a new light in the context of current affairs:

.

.

While political freedom has long been curtailed in Russia, I still saw plenty of evidence of liberal, open and internationally oriented youth scenes in 2017, e.g. at this cultural and design hotspot called ArtPlay in a converted factory complex in Moscow:

.

.

How well this will be able to function in the future is questionable given the many international ties this was built on that will now be at least difficult, if not severed altogether.

Similarly, I was impressed with the vibrant craft-beer scene in Russia, and not only in the big cities but even in places as far from Moscow as Perm. And the quality of many brews I sampled was top-notch, at least on a par with what you could get in the USA or Europe, often even better. In Moscow I visited one particular taproom repeatedly, both for its wide range of superb beers and for its cool underground rock-culture atmosphere – also exemplified by some of the staff, as you can see here:

.

.

I now fear for the continuation of this scene. With no Western tourist customers and limited if not cut-off access to, say, imported American aroma hops, the craft-brewing scene in Russia will inevitably also face difficult times ahead.

I was also impressed with how much Moscow had changed for the better in culinary terms in general. In the 1980s food was definitely a lowlight of my trip to Leningrad, and in the late 1990s the best one could hope for beyond traditional Russian fare was to find a Georgian or Armenian restaurant (especially from a semi-vegetarian perspective those have always been a godsend anywhere in the former USSR). In 2017 I found that the culinary transformation Moscow had gone through was simply stunning. Not only was there a wide range of superb international cuisines available, regional creative Russian cooking was also on the rise. In fact I have rarely, if ever, eaten so well in any city on so many consecutive days anywhere in the world. Some useful inspirations regarding new and “in” restaurants (from Peruvian to Hawaiian) I gathered from the Aeroflot in-flight magazine on my inbound flight to St Petersburg at the beginning of my trip.

.

.

I made a note of five restaurants mentioned in this article, visited them all and every single one of them was superb, without being cripplingly expensive (for us foreigners, that is – helped by an advantageous rouble exchange rate at the time; for not-so-well-off locals these places would still have been too pricey). One of them was a “New Nordic” (Scandinavian) cuisine restaurant called “Bjørn”, which means ‘bear’ in Swedish and Norwegian – and that’s of course quite fitting for Russia. They even had a bear image made from driftwood on one of the walls:

How much this vibrant culinary scene will be affected by the recent developments and sanctions is difficult to predict, but in the longer term, if the economy remains under strain, there are bound to be casualties amongst these businesses too.

In the Western media the most prominent names of companies pulling out of or suspending operations in Russia have been mostly big corporations or luxury brands of designer clothes and such like … I won’t give names, but I’m pretty sure you will have heard of some examples. Personally, I wouldn’t mind much if luxury fashion design outlets disappear – they’re an alien world to me anyway. Nor would I mind much an absence of the standard global fast-food presence from blighting any cityscape. But I do acknowledge that it amounts to a kind of cultural change.

I can imagine that the foremost luxury shopping temple in Russia, Moscow’s GUM “department store” (in 2017 basically just a conglomeration of Western-brand-name outlets) will be quite affected by the latest developments. Here’s a photo of the inside of this cathedral of shopping taken from the upper gallery when I was last there:

.

.

Funnily enough, amidst all this international luxury brand extravaganza that GUM has developed into, there is one curious survivor from the Soviet era at stall No. 57: a proper old-school self-service canteen where you can still find old traditional Russian fare for little money, such as kasha (buckwheat) with mushroom sauce, “herring in a fur coat”, beetroot and cabbage salad with nuts, plus “kompot” (a kind of flat fruit lemonade):

.

.

But despite recent glimmers of hope that a diplomatic solution may not be all but impossible and a descent into a global Third Wold War could be avoided, the situation remains more than tense. And I fear that the longer-term consequences for Russia won’t go away so easily in any case. The damage has been done. A simple return to what things were like before the war seems impossible.

Let’s just hope that the damage will remain in the somehow “repairable” bracket, even with much effort required, rather than leading to a further deterioration of world affairs. The planet really doesn’t need this. Not only are all those millions of innocent civilians suffering, war is also the worst-possible scenario for the environment. The military is already the single worst polluter and contributor to global warming in peacetime. In war it’s another level. What the world needs is the precise opposite of this war: curbing egos, nationalism and aggression and uniting in a global effort to make this planet survivable in future decades. Right now it’s not looking good. Either we go down in a nuclear Armageddon (still a very real possibility), or we have to make up for massive setbacks in the already rather feeble efforts of slowing climate change.

These last few remarks may seem a bit out of place in the context of the current Russia-Ukraine war, when all eyes are on the civilian victims and their immediate needs. But the planet is also a victim in this. And while there may be various ways to wriggle out of a war, there is, to repeat myself from my recent Easter Island post, no “planet B”.

So let me finish with one final evocative photo I took on my Russia trip in 2017, namely from the revolving bar-restaurant in Moscow’s Ostankino TV tower during heavy weather … again, you can interpret this in various ways … :

.

.